For this inaugural blog, I thought that I would recount several of my Connecticut River experiences that fostered the strong emotional attachment that I hold for the River today. They happen to intersect five of the articles that either appeared in the first issue or are planned to appear in one or more of the next three quarterly issues of the magazine. Why start here? Because a wise consulting practice called Vital Smarts once wrote persuasively,

“Finding a way to encourage others to both understand and believe in a new point of view may not be enough to propel them into action…. At some point, if emotions don’t kick in, people don’t act.”

Patterson et al., Influencer: The Power to Change Anything

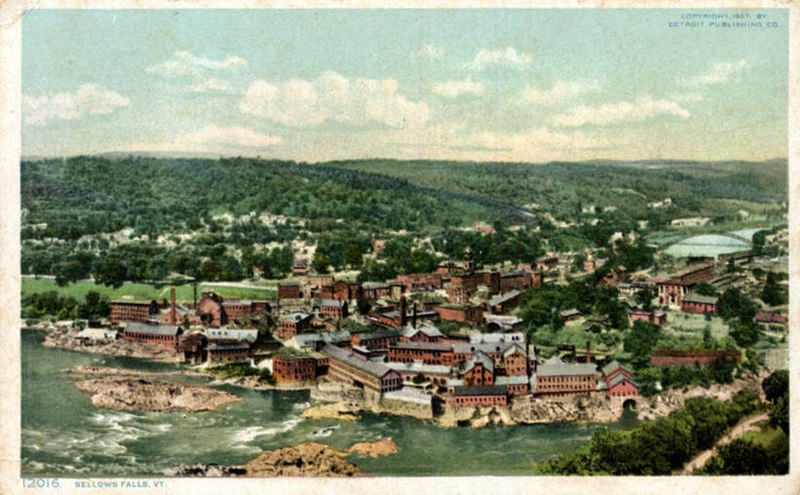

Growing up as a Boy Scout in a small town outside of Boston, my first encounter with the Connecticut River was a 45-mile, downriver canoe trip that started with overnight camping near the Dartmouth Outing Club in Hanover, NH. (An article in the upcoming Summer 2020 issue of Estuary magazine on page 7 describes the 1773 journey of John Ledyard in a dug-out canoe over part of the same route.) The next day, under clear skies with no incidents, we neared the half-way point and stopped on the Vermont side to scramble up a bridge embankment to restock our supplies at a general store. That night, we pitched our tents and camped out in a dairy farmer’s field that bordered the river on the New Hampshire side. The next morning, we awoke to several curious cows rummaging through our campsite; we were anxious that they would crush our tents, but our fears were unfounded. The rest of the trip through bucolic landscapes proceeded uneventfully, and we hauled out in the vicinity of the Bellows Falls Dam. For a 13-year-old boy, this was the trip of his young life.

Bellows Falls, Vermont

I did not return to the Connecticut again until after I was married and in graduate school. This time, about a week before Thanksgiving, I went deer hunting with my father-in-law in the thick woods surrounding the Connecticut Lakes in far northern New Hampshire—the very source of the Connecticut River. The weather was bitterly cold and the snow was waist high, which made walking any distance exceedingly difficult, even with snowshoes. We came home empty-handed but had enjoyed the company of our back-woods host, a habitual punster (likely his defense against cabin fever), and his wife, who gave me my first taste of deer-heart stew for dinner one evening in their kitchen that was overheated by a glowing wood stove.

Years later, toward the end of winter, I came back to this region to attend my niece’s wedding at the nearby Balsams Grand Hotel and Resort, which has many recreational amenities, including hiking, mountain biking, and cross-country skiing trails. The Balsams, by the way, houses in its bowels a small, wood-paneled room that was the earliest polling place to open for presidential elections in the United States. At that time, as I recall, the diminutive town of Dixville Notch, NH, had a turnout of around 12 voters at midnight at this polling location.

Many more years passed before I got back to the Connecticut River. During this time, we raised our family in upper New York State, moved for a period to West Virginia, and then moved back to New England, where we settled in Glastonbury, CT, which has a serpentine border on its west side with the Connecticut River. It was at the ferry landing in Rocky Hill, just across the river from Glastonbury, that I purchased my first “pair” of fresh roe from a river-caught shad. I was subsequently taught by a long-time resident how to cook this delicacy. As fate would have it, sometime later I returned the favor by cooking shad roe for this friend just a couple of days before he died. His last words to me, “Don’t boil the water,” will forever remain in my memory as an indelible part of his no-frills recipe: poach the roe in simmering water for about 20 minutes; then carefully transfer to a well-buttered skillet, heated to medium temperature, and fry until golden brown. Handle the roe lobes very gently so as not to break them at any step. (For a fancier recipe, see the article “What’s for Dinner?” on p. 69 of Estuary magazine, Spring 2020.)

While living in New York State and then in West Virginia, I took up bicycling with a passion. This time I was able to afford decent road bikes, as opposed to the junkers that I rode, also passionately, as a kid. To my delight, I was pleased to find from my base in Glastonbury a multitude of exhilarating riding routes that thread through the River’s watershed, track along the River’s shores, and sometimes cross it. These routes span south to the mouth of the river at Long Island Sound and north to Westfield, MA. Most feature gorgeous scenery along the river and its tributaries; crossings are via bridges (Baldwin, East Hampton, Arrigoni, Founders, Veterans) or ferry (Glastonbury-Rocky Hill, Chester-Hadlyme).

One of my favorite northern rides, organized by River’s Edge Cycling in Sunderland, MA, is a 100-mile round trip that starts in Northampton, MA, and follows the west side of the River to Brattleboro, VT, after passing through the historic Massachusetts towns of Deerfield and Turners Falls.

Turners Falls, Massachusetts

The route then crosses into New Hampshire the next day and follows the east side of the River back to Northampton. (Forthcoming is the article “Cycling the Valley” on page 13 of Estuary magazine, Summer 2020.)

In addition to taking in the beautiful scenery on these rides, we manage to find outstanding restaurants for lunch. One particularly cherished ride that traverses the hilly terrain of the watershed between Marlborough and Chester, CT, has the name “Pie Ride” in recognition of the huge (18-lb) apple pie that chef-owner Dennis Welch bakes for us at his restaurant, The Wheat Market. One 1 ½ lb slice of this pie is enough for breakfast, lunch, and dinner combined; the trick is to bicycle up the hills on the 20-mile return trip without “losing” the pie.

In case you haven’t guessed already, bicycling and sharing meals with a group of friends in the exquisite surroundings of the Connecticut River renews my soul and has added considerably to my emotional bond with the River.

I will conclude my story in the next blog.

A 1 1/2 lb. piece of pie waiting to be eaten.