“Sunset Over the Connecticut River”

Photo by Susanne Hall

What’s for Dinner?

Pekin Duck and Peking Duck are wildly different! Peking Duck is the cooking preparation and presentation of a duck dish originated in Peking (Beijing), China, during the Imperial era and is still popular today.

The Elusive Bobcat

Meet the bobcat, an elusive, captivating animal that is prevalent in the Connecticut River Valley, yet one that many of us—myself included—have rarely seen in the wild.

From the Publisher:

This issue of Estuary contains our first article by a descendant of Indigenous people. These people inhabited North and South America for thousands of years, maybe 12,000 years, long before the word “America” existed.

About Our Blog:

In case you missed it, our luscious website (estuarymagazine.com) also features a blog.

Moose

Moose comes from the Algonquin word Mooswa, meaning “the one who strips twigs.” To fulfill its life functions, the North American moose, Alces alces, requires some 10,000 calories per day, equating to between 50 and 100 pounds of food.

Crossing the Bar

There’s a sailor superstition about changing a boat’s name. State of New York, largest and costliest steamer ever to run on the Connecticut River, was to be called Vermont.

Colt

Heading up the Connecticut River, just below downtown Hartford, the west bank reveals an incongruous vision. Eyes are pulled to a blue, onion-shaped dome, spangled with golden stars and tipped with a rampant colt finial.

Qwannitucket

Qwannitucket, the Long Tidal River land known as the Connecticut River Valley, is the living pulse of this region currently known as New England. This article, which focuses on the lower valley of the Connecticut

River, is intended to raise awareness in modern society about the beautiful

resource that connects north to south, mountains to ocean, the swimmers, winged, four-legged, two-legged, and all the living beings known and unknown that dwell here.

Loons

I saw my first common loon in January of 1958, at the mouth of the Connecticut River. In those days, Griswold Point was connected to the mainland. As a twelve year old, on my own, I could hike dry-shod to the point’s end and survey the River’s mouth.

The Hartford Wits & the World They Made

On the west shore of the Connecticut

River, the town of Hartford bustled

in the morning light. People gathered

at the market on the town green,

in taverns, and in coffeehouses,

where a few years earlier the local

secret society might have planned a

revolution, spurred on by the demon

caffeine.

Dams, Fish, & Relicensing Major Power Plants

Believe it or not, there are more than 3,000 dams on the mighty Connecticut River and its myriad tributaries.

VENTURE SMITH’S LONG STRUGGLE

In 1776, at the dawn of the American Revolution, Venture Smith stood on

the banks of the Connecticut River a free man. He had his own farm, his

wife and child lived with him, and he had a prosperous 130-acre farm in

the village of East Haddam. It had taken him a long time to get there, and the journey was not of his own choosing.

Hydropower

We are publishing two articles about the hydropower industry in this issue of Estuary. The first offers an overview of, or a peek at, the hydropower industry, an important but largely behind-the-scenes stakeholder in the Connecticut River watershed.

Cold Weather Safety

“Maybe better that we die because then we won’t be embarrassed.” So muttered I to my duck hunting partner as the outgoing tide took our eight-foot pram and us, shivering and soaked to the skin, out from the mouth of the Connecticut River towards the grim waves of Long Island Sound on a freezing winter day many years ago.

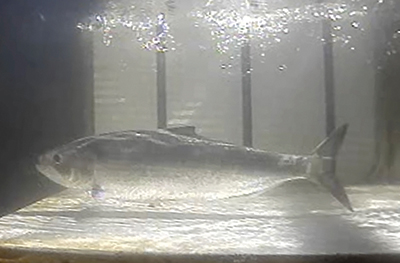

Introducing a Regular Column About Migratory Fish in the Watershed

Some of the most historical and ecologically-significant migrations of the Connecticut River are missed by most. These are the annual migrations of fish—specifically diadromous fish.

Turners Falls Area Winter Birding

In March 2019, a flock of 20 tundra swans made an unexpected overnight visit to a historic canal at Turners Falls, Massachusetts, one of the Connecticut River watershed’s finest winter birding destinations. The swans, which breed in the Arctic and overwinter on the mid-Atlantic coast and other regions, delighted fortunate observers before departing the next morning.

Hydrilla

By now, knowledge that invasive plants are bad news is pretty widespread. Numerous articles and agencies cite “billions of dollars” in damages annually to agriculture and fisheries; they are the “leading cause” of population decline and extinction in animals.

The Falls

A poem by David Leff, an award-winning essayist, poet, and former deputy commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection.