Riverside Service: Cherish and Celebrate the Connecticut River Hosted by St. Ann’s of Old Lyme and Bishop Ian Douglas, it was a great evening of fellowship, recognition of “water of life” and of the rivers in all our lives. In the second half of the video, Connecticut River Conservancy’s Executive Director Andy Fisk talks about the importance of faith and …

From the Publisher

Volume II, Issue I. These few words, in fact, speak volumes. Estuary’s Volume I, Issue I, better known as Spring 2020, came out, arguably, at the worst possible time for a new print magazine. The publishing industry had long since administered last rites to print magazines in general, so why did we think we could succeed with Estuary?

From the Publisher:

Volume II, Issue I. These few words, in fact, speak volumes. Estuary’s Volume I, Issue I, better known as Spring 2020, came out, arguably, at the worst possible time for a new print magazine. The publishing industry had long since administered last rites to print magazines in general, so why did we think we could succeed with Estuary?

Your Best Shot

“Sunset Over the Connecticut River”

Photo by Susanne Hall

About Our Blog:

In case you missed it, our luscious website (estuarymagazine.com) also features a blog.

A Magnificent Obsession: Our Fascination with Wildlife (Part 3)

We will now consider another source of fascination with wildlife to continue our investigation.

A Magnificent Obsession: Our Fascination with Wildlife (Part 2)

We will now consider another source of fascination with wildlife to continue our investigation.

A Magnificent Obsession: Our Fascination with Wildlife (Part 1)

One theory of our fascination with animals holds that we observe them, in their native habitats and in zoos, to discover deep origins of our current behavior. In short, we view animals as reflections of ourselves and we watch them to learn more about us.

Invitation to Public Comment Meeting for the Proposed Connecticut National Estuarine Research Reserve

You are invited to attend a virtual public comment meeting for Connecticut’s proposed National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR).

The meeting will be held on Tuesday August 4th, 2020, from 7:00 to 9:00 PM EDT via WebEx.

Become an Environmental Activist (Part 2)

Last time, we parted with my advice to first become informed about the state of the environment and then develop the conviction that you can make a difference to the environment by volunteering in an area that interests you.

If you are still left wondering what you can do, you can start your involvement by looking no further than your personal lifestyle, back yard, or neighborhood.

Become an Environmental Activist

I started to write this blog on the topic of citizen science for the Connecticut River environment but soon realized that the concept could be too narrowly interpreted as just “science.” To be clear, citizen science usually involves a collaboration between non-scientists and scientists in which non-scientists collect data needed by scientists to resolve real-world issues.

Solving Environmental Problems

Environmental problems can be complex and hard to resolve. The complexity arises because the components of the environment are linked, and their interactions may be separated by both time and distance.

The Connecticut River’s Tranquility

In these times of stressful living, designed to contain the coronavirus, more and more people are seeking solace in nature. The fall 2020 issue of Estuary magazine contains several personal essays on this topic.

Editor’s Log: Island Solitude

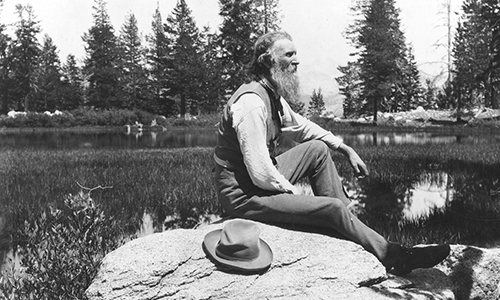

“Come to the woods, for here there is rest,” wrote John Muir, the pioneering environmental activist and writer. “There is no repose like that of the green deep woods.” Few knew the healing power of nature better than Muir (1838–1914), whose deep connection with the outdoors was forged through a convalescence.

My Connecticut River, cont…

We weren’t settled for very long in Glastonbury before I joined the Connecticut Audubon Society and became a member of the Regional Board of Directors of its nature center in Glastonbury and then was elected to the state Board of Directors. These responsibilities introduced me to still more dimensions of the Connecticut River.

My Connecticut River

For this inaugural blog, I thought that I would recount several of my Connecticut River experiences that fostered the strong emotional attachment that I hold for the River today. They happen to intersect five of the articles that either appeared in the first issue or are planned to appear in one or more of the next three quarterly issues of the magazine.