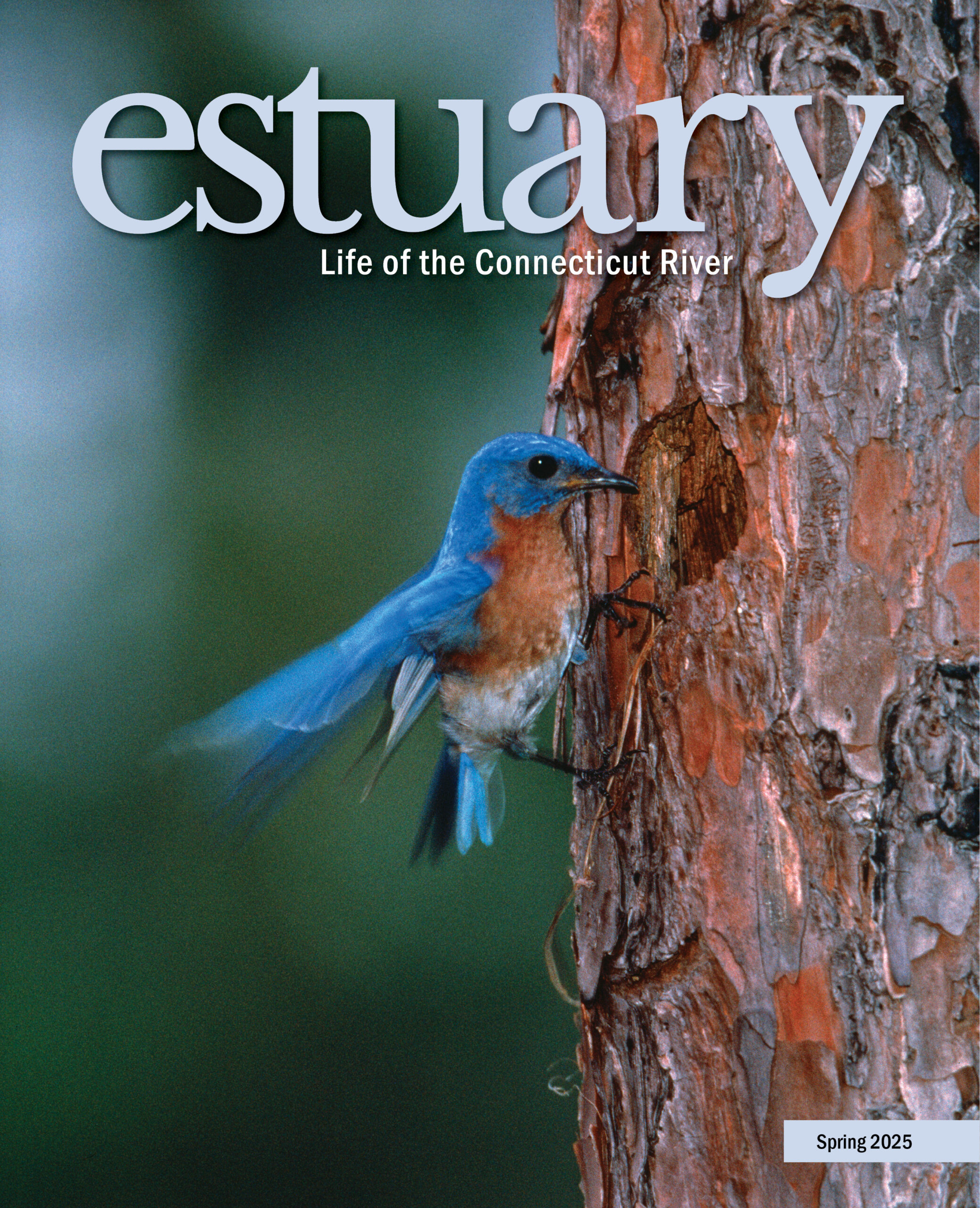

This article appears in the Spring 2025 issue

This article appears in the Spring 2025 issue

One could walk the length of the Connecticut River and never think of Wallace Stevens. The river, whose 410 miles contain astonishing variety of breadth and depth, offers the walker seemingly endless ways to measure its form: consider its width of 2,100 feet at Longmeadow, Massachusetts, and just down the highway in Connecticut, a mere 600 feet between Bodkin Rock in Portland and the Middletown shore. Or the difference between its daunting 130-feet depth at French King’s Bridge in Gill, Massachusetts, and the river’s shallowest point at its mouth in Old Saybrook, where low tide offers up a mere eight feet of brackish water.

Indeed, the poet Wallace Stevens need never enter the mind when we think of the metrics of length, width, and depth. But beauty, changeability, and a different kind of depth—that of the intellect and the soul? To truly understand these qualities, we do need Stevens, the internationally renowned poet who also walked the Connecticut River’s shores from his arrival in Hartford in 1915 until his death in 1955.

Stevens most famously memorialized the river’s infinite variety in his 1954 poem, “The River of Rivers in Connecticut”:

Poet and insurance executive Wallace Stevens. Image Credit: Illustration by James Baker.

There is a great river this side of Stygia

Before one comes to the first black cataracts

And trees that lack the intelligence of trees.

In that river, far this side of Stygia,

The mere flowing of the water is a gayety,

Flashing and flashing in the sun. On its banks,

No shadow walks. The river is fateful,

Like the last one. But there is no ferryman.

He could not bend against its propelling force.

It is not to be seen beneath the appearances

That tell of it. The steeple at Farmington

Stands glistening and Haddam shines and sways.

It is the third commonness with light and air,

A curriculum, a vigor, a local abstraction…

Call it, one more, a river, an unnamed flowing,

Space-filled, reflecting the seasons, the folk-lore

Of each of the senses; call it, again and again,

The river that flows nowhere, like a sea.

This is not the only poem where Stevens hints at his connection to this body of water. In his 1954 poem, “Of Hartford in a Purple Light,” he writes:

But now, as in an amour of women,

Purple sets purple round.

Look, Master, see the river, the railroad, the cathedral…

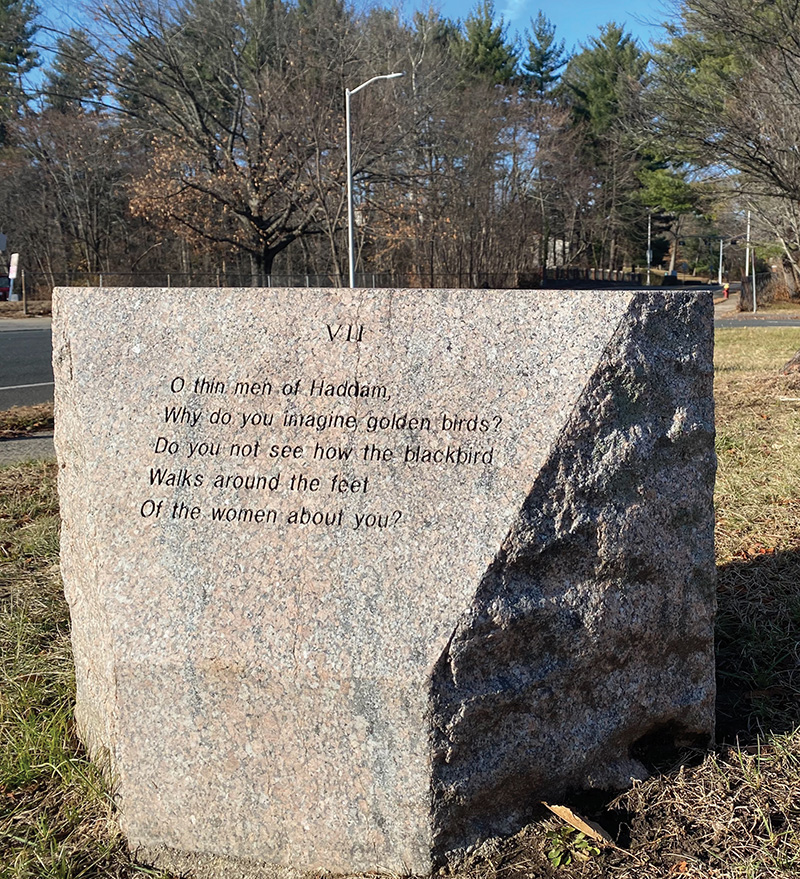

And in the seventh verse of “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” Stevens asks:

O thin men of Haddam,

Why do you imagine golden birds?

Do you not see how the blackbird

Walks around the feet

Of the women about you?

Wallace Stevens’s house on Westerly Terrace, Hartford. In the foreground is the last stone in the Wallace Stevens Walk, a self-guided walking tour that retraces the route Stevens walked each day to work. The walk’s thirteen stones are inscribed with a stanza from his poem, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.” Image Credit: Christine Palm

However, since Stevens famously eschewed confessional poetry, critics often warn readers not to read too much of Stevens’s own life in his words. Obsessed as he was with the endless cycles of desire and despair, Stevens kept a great distance from himself; he speaks in the third person, inserts made-up people (Ramon Fernandez, Peter Quince, Chieftain Iffucan) for himself, and keeps any self-revelations completely buried beneath his dazzling, imaginative words.

One could question whether “The River of Rivers” is really about the Connecticut River at all. On his lunch break from The Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company (now the Hartford Financial Services Group) where he served as vice president, he often walked east down Asylum Avenue, and across Main Street to the riverbank. After work he was known to belt down several bourbons in the erstwhile Canoe Club in East Hartford. But, of course, these facts might be coincidental.

From time to time poetry critics have suggested that “The River of Rivers” could, after all, be any river. Stevens scholar Jerry Griswold says, “Critics have gone wrong when interpreting this poem by suggesting that it proposes a contrast between the mythological river Styx and an actual waterway in Connecticut; the Farmington, Housatonic, and Connecticut rivers have been proposed as candidates. None of these suggestions, however, make geographical sense because as (Helen Vender) has noted, ‘more than 30 miles separate the towns of Farmington and Haddam—thus an observer could not simultaneously see Farmington glistening or Haddam shining.’”

Stevens was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, into a strict family of Dutch-German extraction. From his mother, a church pianist, he acquired a love of musicality in language—a quality that eventually infused every aspect of his writing. Even as a child, he enjoyed taking long walks—often many miles at a time—and it was a habit he would keep all his life. He was observed by neighbors, in fact, composing poetry in his head as he walked, using the beats of his footfall to pace the rhythm of his words.

Wallace Stevens Walk, Stanza VII, refers to the Connecticut River town of Haddam. The stone is in front of the Classical Magnet High School, Asylum Avenue, Hartford. Image Credit: Christine Palm

After a brief stint as a journalist, Stevens entered the law as his father had wished him to do. He moved to Hartford where he lived a dual life as poet and a consummate businessman. He was well-respected (even feared) at his job which was, essentially, to assess (and avoid) risk. How ironic, then, that among poets—writers who generally pride themselves on pushing boundaries—Stevens was among the greatest risk-takers in his playful and strange use of language.

Stevens was, first and foremost, a poet of place. At one point in his career Stevens was required to travel. Usually going by train, he was frequently moved by the infinite variety of the American landscape and drew inspiration from it. He was equally at home tending his roses and peonies behind his house on Hartford’s Westerly Terrance as he was watching the wind-whipped palm trees in Key West, where he spent the winters. In this way, the Northern landscape and the tropical one became like two poles of his life—the “junipers shagged with ice” in the poem “The Snowman,” were just as moving to him as the ocean off the Florida coast, where he observed a woman who “sang beyond the genius of the sea” and where the sea itself was “like a body fluttering its empty sleeves.”

In his Editor’s Preface to Garnet Poems: An Anthology of Connecticut Poetry Since 1776 (Wesleyan University Press, 2012), Dennis Barone says, “The more one reads Stevens’s poetry, the more one is overwhelmed by its beauty and the intellect of the mind that made it, a mind deeply rooted in Connecticut: its topography, its seasons, its weather.”

Of course it is possible to love the Connecticut River without loving Wallace Stevens. But it’s also possible to drive along Route 9 and observe that the sun looks pretty as it glistens off the ice that formed on the river overnight. Or, we can stop the car, walk to the river, sense the sun throwing shards of light into our eyes, step tentatively on the ice, listen for it to crack, hear its voice echo off the river’s depths, and then return to our car glad of its safety and warmth. So it is with bringing Stevens along with us to the river, rather than leaving him in the car or on the bookshelf.

If we do keep him in our mind (and perhaps our heart and soul), we will truly appreciate the river’s “gayety,” see its “vigor,” sense its “commonness,” and feel its “propelling force.” Only then will we hear the “folk-lore / Of each of the senses; (and) call it, again and again / The river that flows nowhere, like a sea.”

Christine Palm is the outgoing vice chair of the Connecticut General Assembly’s Environment Committee, where she led a successful effort to establish the Connecticut Office of Aquatic Invasive Species. She is principal of The Active Voice, a student leadership program that combines civics, journalism, and environmental advocacy.