This article appears in the Spring 2025 issue

This article appears in the Spring 2025 issue

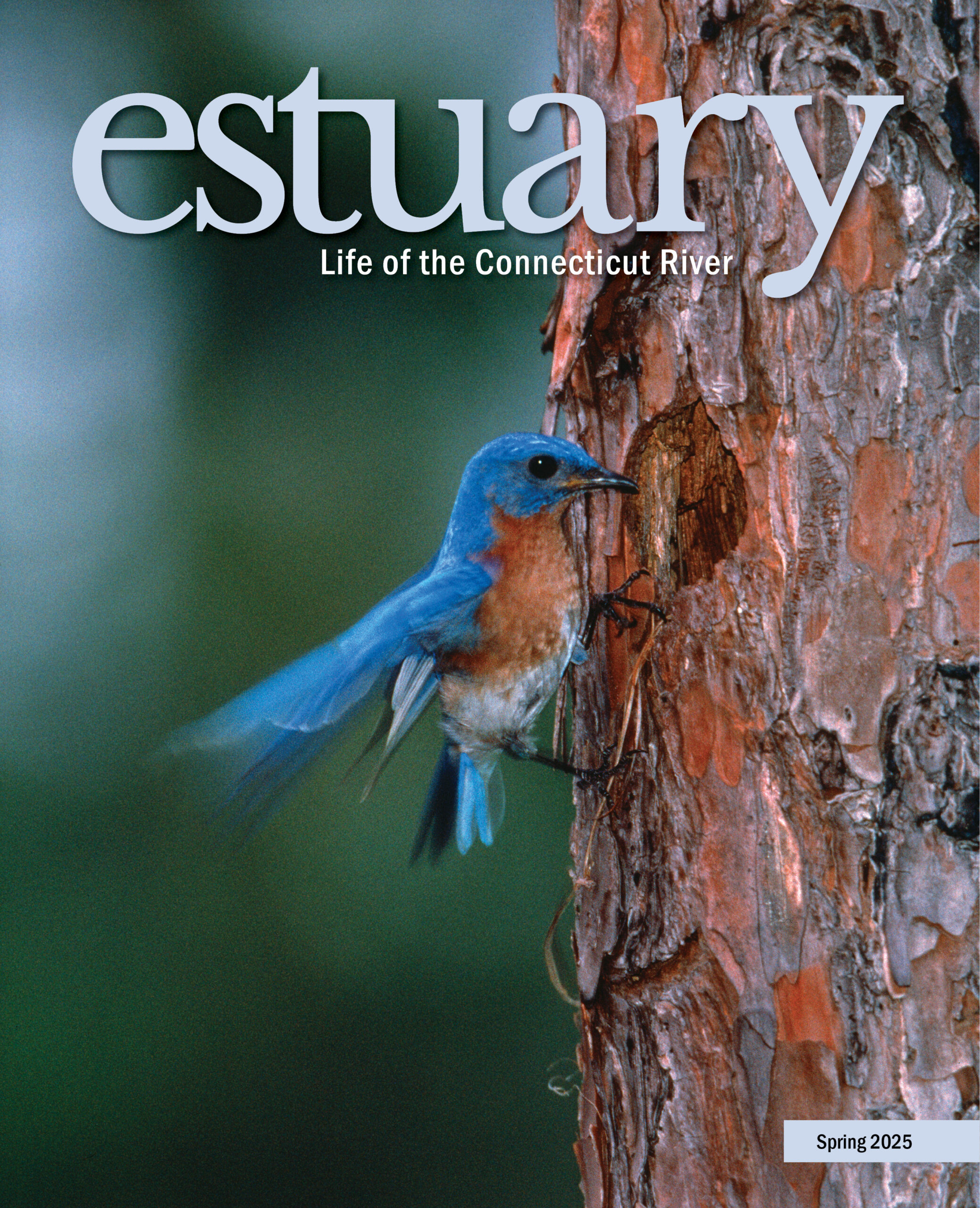

Eastern Bluebird, Female, at Nest, Croatan National Forest, North Carolina, May 2000. ©William Burt

Some birds are unshakably consistent in their nesting ways, and good for them, I say. It’s heartening to know that some lives can sustain such constancy, and thrive.

In our salt meadows at the mouth of the Connecticut, for instance, Clapper Rails nest invariably among the coarse blades of Spartina alterniflora, and in the same meadows the demure Saltmarsh (Sharp-tailed) Sparrow nests within the higher, drier reaches of the marsh, in wiry-fine Spartina patens. In low swampy woodlands just a few miles inland, meanwhile, the petite Brown Creeper tucks its nest under an old loose flap of tree bark; and in drier woodlands the Wood Pewee sets its neat round cup out on a horizontal oak limb—and often at a fork, where it resembles a mere knot.

In a world refashioned hourly by the likes of us, these are among the species disinclined to artificial nest sites, and again, hats off to them; but many others are quite happy to take almost any man-made space available, however tawdry. The historically cliff-nesting Peregrine, for instance. It cares only that a site should have both height and a commanding view, so it’s more likely nowadays to opt for urban high-rise buildings, bridges, electric transmission towers, and granary silos (although a pair did nest successfully along the lower river here at Joshua’s Rock in Hadlyme back in 2008, for the first time in recent memory).

In much of the East, the Common Nighthawk has almost entirely abandoned its ancestral bare-ground nesting sites for the flat gravel roofs of cities, and in some recent instances so too have Killdeers, Least Terns, and even Herring Gulls—although not always with success, as you can well imagine. And speaking of the Killdeer, a most heedless nest site is described by A. C. Bent in his Life Histories series as “between the ties on a used railway track” in Santa Monica, California, back in 1901 (and he reports two other cases of such Killdeer nestings!).

But the birds most to benefit from man’s activity are the hole-nesting types, and above all the infamous House Sparrow and the European Starling. These odious aggressors will seize any nook and cranny they can wangle, at the expense of our own native bluebirds, Screech Owls, woodpeckers, and a host of others.

On a late-May walk down the old village street here in Old Lyme, at every hundred yards or so you hear the dull tink-tink as yet another starling beelines to or from another steeple, attic, belfry or old tree hole with a pinch of food if coming, or a fecal sac if going; and young House Sparrows meanwhile perpetrate their pointless, toneless racket overhead from nests stuffed into wrapped electrical line connectors. One year, a pair of starlings managed to maintain their shabby home behind the bright red flasher on a SLOW sign posted opposite the Old Lyme fire station.

But let’s not underestimate the genius of our native birds for sniffing out creative nest sites. I’m thinking here especially of two wrens (those busiest and snoopiest of songbirds) and two swallows. The crannies, cavities, and burrows that these four alone have exploited range from the ingenious and resourceful to the grisly and outright amusing.

Two Wrens

We’re lucky here in southernmost Connecticut, for here alone in all New England is the Carolina Wren, a common bird, and its rollicking songs a common pleasure to the ear. It’s drawn to human settlements, as A. C. Bent notes well in his Life Histories work; and its nesting sites include not only “a great variety of nooks and crannies in, about, or under buildings” but “such stray receptacles as tin cans, coffee pots, pails, small baskets, pitchers, or empty boxes.” And to these he adds “discarded hats and caps or the pockets of old clothes…mailboxes, bird boxes, old hornets’ nests,” and once even “a farm tractor that was in daily use.”

He cites the account of Dr. Witmer Stone, who wrote in 1911 of a country house near Philadelphia in which “a pair of Carolina Wrens entered the sitting room through a window that was left partly open and built their nest in the back of an upholstered sofa....”

Not long ago, friend Harry Armistead listed out from memory the various “quixotic places” in which he’s found the Carolina “nesting or at least trying to” about his home in rural Talbot County, Maryland. Among them: in a backpack left “on the backside of the back seat” when his “car hatch back was left open”; in “the bicycle basket”; in “several places on my boat, ‘the Mudhen,’ as it sat under the garage car port”; inside “the outside vent of the clothes drier”; and, he writes, “My favorite: inside one of my white waterman’s boots left out a little too long on the front porch.”

When prowling for a Prairie Warbler nest in an old cedar pasture years ago here in Old Lyme, I heard the fuss of young birds coming from the depths of a Red Cedar tree so thick with green that it was all I could do to pry my way in for a look, all the while to the increasing protest of two whining Carolina Wrens. And there packed in against the trunk was this enormous ball of dead brown vegetation, nearly all of it consisting of fine strips of cedar bark.

I had no idea that these wrens might build so vast and un-contained a nest, and in so relatively wild a site—there was no man-made structure within half a mile—but on consulting Mr. Bent I find that, yes, they may indeed nest in “a densely branched cedar.” The aspect of this un-housed nesting of the Carolina brings to mind the woven works of its two fellow wrens of wetland habitats: the Marsh Wren and the Sedge Wren.

“The House Wren,” wrote the nature sage John Burroughs in his 1897 book Wake Robin, “will build in anything that has an accessible cavity, from an old boot to a bombshell.” And to these bizarre examples he might well have added that of twenty-three empty cow skulls left to bleach on Wallops Island, Virginia; and even—so writes Edward Howe Forbush in his hulking Birds of Massachusetts and other New England States (1929)—“a human skull in the house of a doctor.”

On turning back to Mr. Bent, we find that this sly wren of our backyards has also found its way indoors to nest within old boots and flowerpots, tin cans and garbage heaps and teapots, farm machinery, a fishing creel, and “in a bag of feathers”; and outdoors within various parts of pumps, “in the hat and pockets of a scarecrow,” and once “on the rear axle of an automobile which was used daily.”

Two Swallows

Two swallow species, too, are quick to seize upon such ready-manufactured spaces. The burrow-nesting Rough-winged Swallow, for one; it has an eye for drainpipes, culverts, or the crannies under bridges; and each spring here in Old Lyme you’ll see some Rough-wings fluttering about the nooks beneath I-95, where Route 156 runs through.

In Arthur Howell’s Birds of Alabama (1924), you read that these birds nested “on a buttress beneath the deck of a transfer steamboat which made daily trips on the Tennessee River from Guntersville to Hobbs Island, a distance of 24 miles, leaving at 10 a.m. and returning at 6 p.m.” The parents “followed the boat all the way to feed their young.”

The Barn Swallow too is known to choose such mobile homes for nesting. A browse through Bent’s Life Histories will find the testimony of one Captain Harris (1903), who ran steamers on Lake George, New York, and noted that these swallows nested “under the guard-rails” of his active steamers “for the past fifty-five years.”

Mr. Bent cites also one H. S. Swarth (1935), who wrote him of a pair of Barn Swallows that nested for many years on “a narrow-gauge train, which carries passengers and freight over a 2-mile portage from Lake Tagish to Lake Atlin, British Columbia.” Mr. Swarth noted further that “The train crew takes a personal interest in their guests, and for some years the swallows occupied an open cigar box that was fastened for their use under the roof of the open-sided passenger coach.”

The most amusing swallow nesting I’ve encountered was some years ago in a roadside shopping mart somewhere in northern Minnesota, where I was parked before a little restaurant and contemplating whether to go in. Upon a wood facade above the door was painted the word DONUTS, and no sooner had I noticed it than a Barn Swallow shot in through the letter O, then shortly shot back out again.

“The Hirundinadae,” wrote Roger Tory Peterson, “are opportunists; they will never allow civilization to displace them.”

Ingenious though these feathered wits may be that find their way into such nest sites of our making, my admiration goes to those staunch individuals among them that insist on natural sites alone. The few cliff-nesting Peregrines, ground-nesting nighthawks, and the tree-hole-nesting wrens, or bluebirds: they are my heroes, and they bring to mind a newly green spring day I once spent in a stretch of pristine pine savannah down in North Carolina’s Croatan National Forest.

Pristine, I say…well yes, you might encounter the odd truckload of dumped junk—the rusting fridge, the rotting sofa, and the heaped black plastic bags of who-knows-what—but having left such horrors well behind, you find yourself in a wide open Eden of wire grasses and lone scattered longleaf pines, and those peculiar shrub-and-thicket bogs known as pacosins (pronounce pah-co-sin). In this one tract of savannah can be found not only such botanic novelties as Venus flytraps and three kinds of pitcher plants, but such rare nesting birds as the endangered Red-cockaded Woodpecker and Bachman’s Sparrow.

And lurking in the wire grass too, I’m told, are pygmy rattlesnakes.

But what cheered me most that green spring day was finding the uncommon nest sites of two common birds. Within a stretch no larger than a playing field lay several nests (if you could call them that) of Common Nighthawks: not on gravel roofs, but on bare sandy earth beneath the pines. And better still, just eight feet up in a long-standing pine trunk was an old woodpecker hole now occupied by neither starlings or the hateful sparrows, but by Eastern Bluebirds.

And strange though it now seems to say, I’d never seen a bluebird nesting in a tree hole.

What a day that was; and what a place, that little Eden in the Croatan. Here was a relic of the living world as it was meant to be, and here, at least—I hope—still is.

William Burt is a naturalist, photographer, and writer with a passion for wild places—especially marshes—and the elusive birds few people see. He is the author of four books, and his traveling exhibitions have been shown at some thirty-five museums across the US and Canada.