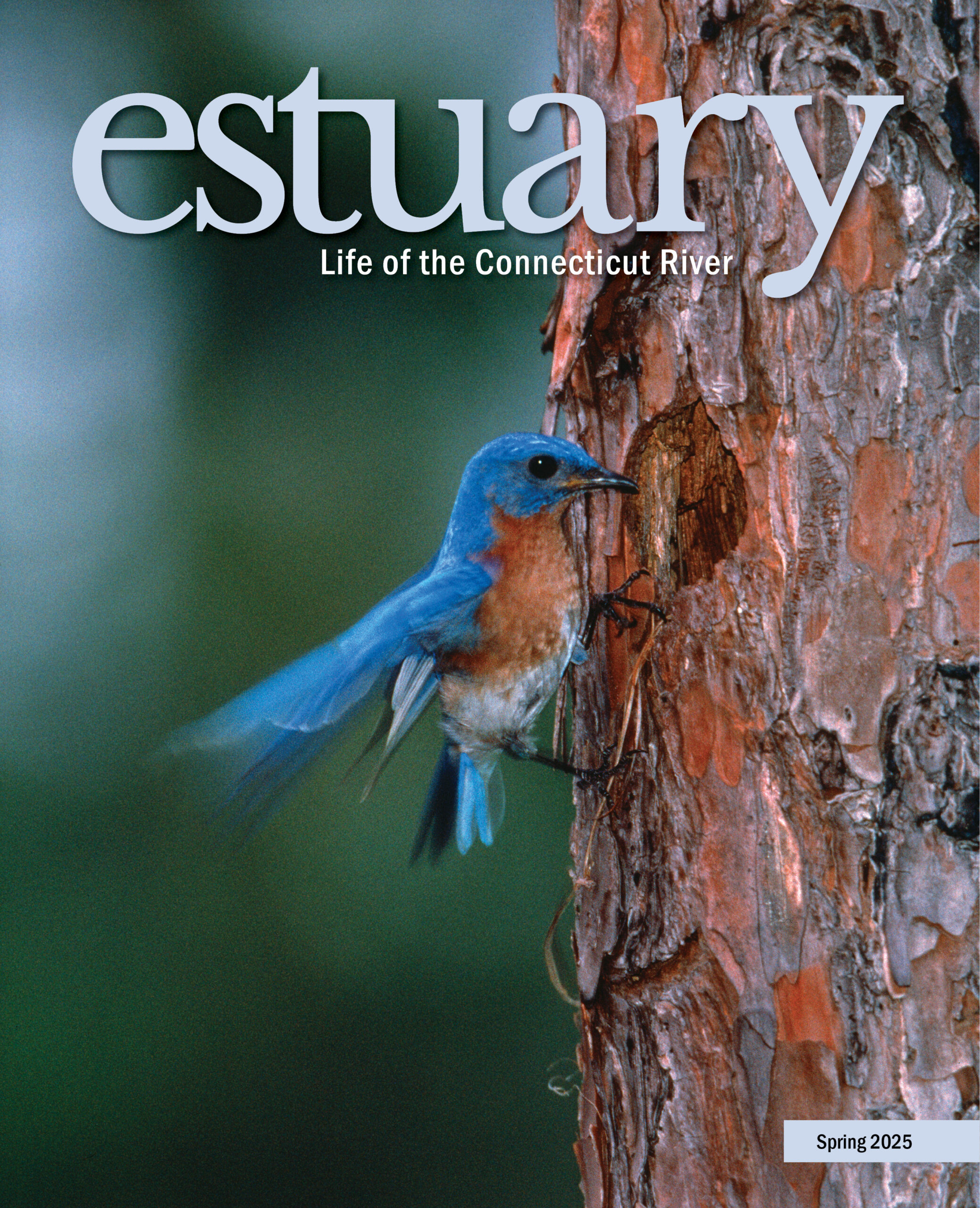

This article appears in the Spring 2025 issue

This article appears in the Spring 2025 issue

Tracking Dinosaurs in the Connecticut River Valley

by John Burk

Eubrontes tracks, preserved in sandstone at Dinosaur Footprints Reservation in Holyoke, MA, came from a large predatory dinosaur. Image Credit: John Burk.

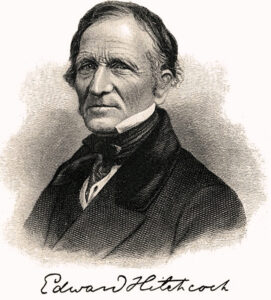

In March 1835 Amherst College professor Edward Hitchcock received a letter about a mysterious discovery in Greenfield, Massachusetts. The writer, a doctor named James Deane, described bird-like tracks embedded in a slab of sandstone rock. Hitchcock initially reacted with skepticism, for geologists had never previously found fossil traces of birds. When he saw the specimens in person, he immediately recognized that the tracks were evidence of prehistoric life unknown to scientists of the time.

Hitchcock’s subsequent research and publications, along with contributions from other figures, established the lower Connecticut River valley as an internationally acclaimed location for fossil tracks. It wasn’t until the late nineteenth century that scientists determined that dinosaurs made the footmarks. More than 30,000 dinosaur tracks have been uncovered in the region.

During a recent visit to Dinosaur Footprints Reservation in Holyoke, Massachusetts, one of several places where visitors can see tracks in their original location, I examined a sandstone outcrop on the west banks of the Connecticut River. Clusters of dinosaur tracks (called trackways) and other fossilized imprints indicated that a variety of prehistoric animal and plant species inhabited the site, which was once the shore of an ancient lake. The most prominent footmarks, Eubrontes, came from a large predatory dinosaur that was twenty feet long.

Remarkably, these fossils date back 190 million years to a geologic era known as the early Jurassic period. When the North American and African continents separated from the land mass called Pangea, the basin that ultimately became the Connecticut River valley formed along a geologic fault. The region’s subtropical lakes, estuaries, and swamps were oases for animals and plants. Imprints made by dinosaurs, fish, insects, and even raindrops dried out in the arid environment and hardened into rock. In the valley’s sandstone belt, which extends from present New Haven, Connecticut, to Northfield, Massachusetts, additional layers of sediment buried the tracks, thus shielding them from erosion.

The environment was far less conducive for preserving bones and skeletons, which decayed in oxygen-rich soils. It was therefore impossible for Hitchcock and other scientists to conclusively determine the species that made the imprints, so they named the tracks separately. Eubrontes, Grallator, and Anchisauripus tracks came from theropods: predators that walked on two feet. The size and stride length of Eubrontes footprints correlate with those of Dilophosaurus, a large carnivore that was discovered in Arizona in 1942. A small dinosaur with a long and narrow stride made Grallator tracks. Otozoum, a rare footmark that has intrigued scientists for many years, came from a giant herbivore that was likely the largest animal of the time.

Although Native Americans, colonial settlers, and quarry workers found fossil tracks in the valley before the nineteenth century, the first documented discovery occurred around 1802 in South Hadley, Massachusetts, when a teenage boy named Pliny Moody unearthed an outcrop with five three-toed footprints at his family’s farm. According to local lore, the mysterious footmarks were popularly attributed to a giant raven from the Biblical story of Noah’s Ark. Moody and his son, Plinius, found more tracks, including the first known Otozoum specimens, on the property during the mid-nineteenth century.

Diorama with dilophosaurus, Dinosaur State Park, Rocky Hill, CT. Image Credit: Elizabeth Normen

Roughly three decades later, Dexter Marsh, a stonemason and laborer, made the discovery that prompted Deane’s aforementioned correspondence with Hitchcock. While building a sidewalk on Clay Hill in the center of Greenfield, he uncovered turkey-like footprints embedded in stones that came from a nearby quarry in Montague.

Hitchcock’s fossil studies, which spanned nearly thirty years, enhanced his legacy as a preeminent early scientist and educational leader. Born in Deerfield, Massachusetts, in 1793, he worked as a pastor before joining Amherst College in 1825. Hitchcock authored numerous articles and books, served as Massachusetts’s first state geologist, and was a founder of the organization that became the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He also served as Amherst College’s president from 1845 to 1854, and helped establish Mount Holyoke College and the University of Massachusetts.

Determined to learn the source of the imprints, Hitchcock searched quarries, sandstone outcrops, and sidewalks throughout the Connecticut River valley in 1835. He published an account of his preliminary findings in the American Journal of Sciences and Arts the following year, which generated considerable interest and debate among scientists in America and Europe. By the early 1840s, geologists accepted Hitchcock’s conclusion that the fossils were prehistoric footprints.

Hitchcock ultimately collected thousands of tracks and fossils, which he meticulously archived at Amherst College. His first named specimen, an Eubrontes footmark, came from a quarry at what likely is the present site of Dinosaur Footprints Reservation. In Ichnology of New England, a comprehensive report published in 1858, he chronicled imprints attributed to 119 species, including birds, marsupials, lizards, tortoises, crustaceans, insects, and worms.

Based on the limited geologic and evolutionary knowledge of the time, Hitchcock theorized that giant birds made the tracks, a belief he maintained until his death in 1864. Scientists such as the noted Yale University paleontologist John Ostrom and his protégé Robert Bakker subsequently established ancestral connections between dinosaurs and birds.

Deane, who authored twelve articles on fossil tracks, continued to collaborate with Hitchcock until the 1840s, when both men engaged in a prolonged feud over credit for the discoveries. Before his death in 1858, Deane started a richly illustrated book titled Ichnographs from the Sandstone of Connecticut River. Published posthumously with assistance from Hitchcock and other colleagues, it was the first American scientific work that extensively used photographs.

A historical dinosaur track quarry at Barton Cove yielded many significant fossil specimens during the nineteenth century. Image credit: John Burk

Inspired by his find, Marsh became an accomplished amateur geologist and fossil collector who received honorary memberships from several prestigious scientific societies. Utilizing a homemade boat, he extracted tracks from outcrops along the Connecticut River. Marsh displayed hundreds of tracks and other natural history artifacts in a museum at his home. After his death in 1853, Hitchcock purchased part of the collection for Amherst College.

Many of Hitchcock and Marsh’s specimens came from a quarry and farm on the banks of the Connecticut River in Gill, Massachusetts. Roswell Field, who owned the property, made many significant fossil discoveries on his land, which Hitchcock described as a “rich paleontological mine.” Scientists from around the world, such as the renowned English biologist and anthropologist Thomas Huxley, visited the quarry.

At the 1859 meeting in Springfield, Massachusetts, of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Field was the first person to propose that the Connecticut Valley tracks came from reptiles. “If I can rightly decipher these fossil inscriptions, impressed on the tombstones of a race of animals that have long since ceased to exist, they should all of them be classified as Reptilia,” he stated.

Edward Hitchcock, noted American geologist, paleontologist, and President of Amherst College. Image Credit: From A History of Amherst College During the Administrations of Its First Five Presidents by William S. Tyler, 1895

Field’s former quarry now lies within a nature preserve owned by First Light Power on the east side of Barton Cove. A one-mile hiking trail leads through a portion of the quarry and adjacent sandstone outcrops. Several dinosaur tracks are visible on a rock slab near the top of a staircase, though weathering has reduced the prominence of the impressions. Another slab with footprints of two dinosaurs is on display at the Great Falls Discovery Center in nearby downtown Turner’s Falls.

The Trustees of Reservations, the nation’s first private land protection organization, established Dinosaur Footprints Reservation in 1935 after construction workers discovered the site while building Route 5. A popular destination for researchers, school groups, and families, the eight-acre property contains more than 800 dinosaur tracks and also imprints of plants, invertebrates, and water marks.

After identifying nearly thirty trackways that faced the same direction at Dinosaur Footprints Reservation, Ostrom proposed that dinosaurs may have been social creatures that traveled or hunted in groups. The late former University of Connecticut paleontologist Patrick Getty and other researchers discovered that most of the tracks paralleled the edge of an ancient lake, which likely influenced their orientation.

Another remarkable find at Rocky Hill, Connecticut, in 1966 led to the creation of Dinosaur State Park, a designated National Natural Landmark that preserves one of North America’s largest dinosaur track sites. While excavating the site of an office building, a bulldozer operator unearthed two trackways that contained more than 2,000 footprints.

The park’s exhibit center features a geodesic dome that protects 500 imprints (mostly Eubrontes), some of which have visible claw marks. The other trackway was reburied in 1976 to preserve the fossils. Varied states of preservation of the tracks likely indicates they were made over an extended period of time. Other attractions include a life-size Dilophosaurus model, interactive dioramas, a gift shop, an arboretum, and two miles of walking trails.

In nearby Middlefield, Connecticut, Powder Hill Dinosaur Park preserves a former quarry with approximately 125 Eubrontes, Grallator, and Anchisauripus tracks. Workers discovered the fossils in 1848 while extracting stones for construction of an industrial dam. The town of Middlefield established a small park after acquiring the property from Yale University in 1976.

Amherst College’s Beneski Museum of Natural History houses the extensive dinosaur track collection of noted geologist Edward Hitchcock. Image credit: John Burk.

After touring field sites, I stopped by Amherst College’s Beneski Museum of Natural History, home of the world’s largest and most researched dinosaur track repository. Completed in 2006, the three-floor facility contains more than 200,000 objects, including displayed skeletons of dinosaurs and Ice Age mammals such as a giant Columbian mammoth and a mastodon.

The well-designed lower level, which features rock slabs displayed on sliding panels and lighting that highlights details of the fossils, houses Hitchcock’s extensive collection. Longtime museum educator Alfred Venne pointed out historically significant specimens such as Moody’s 1802 discovery and Marsh’s find in Greenfield, which continue to intrigue and inspire researchers and visitors.

For a comprehensive history of dinosaur track discoveries in the Connecticut River valley, visit Impressions from a Lost World, an online exhibit compiled by the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association of Deerfield, Massachusetts, at dinotrackdiscovery.org.

John Burk is a writer, photographer, and historian from western Massachusetts whose credits include books, guides, and articles in nature and regional publications.

Beneski Museum of Natural History

11 Barrett Hill Drive, Amherst, MA

Open Tuesday to Sunday year-round

amherst.edu/museums/naturalhistory

Dinosaur Footprints Reservation

1099 US Route 5, Holyoke, MA

Open April 1 to November 30

thetrustees.org/place/dinosaur-footprints/

Barton Cove Dinosaur Quarry

82 French King Highway (MA 2), Gill, MA

Accessed from the campground, a one-mile nature hike passes an abandoned dinosaur footprint quarry.

firstlight.energy/stewardship/barton-cove-and-munns-ferry-campgrounds/

Dinosaur State Park

400 West Street, Rocky Hill, CT

Grounds open daily

Exhibit center open Tuesday–Sunday

ctparks.com/parks/dinosaur-state-park

Powder Hill Dinosaur Park

309 Powder Hill Road, Middlefield, CT

This small-town park is open year-round. No facilities.