This article appears in the Spring 2025 issue

This article appears in the Spring 2025 issue

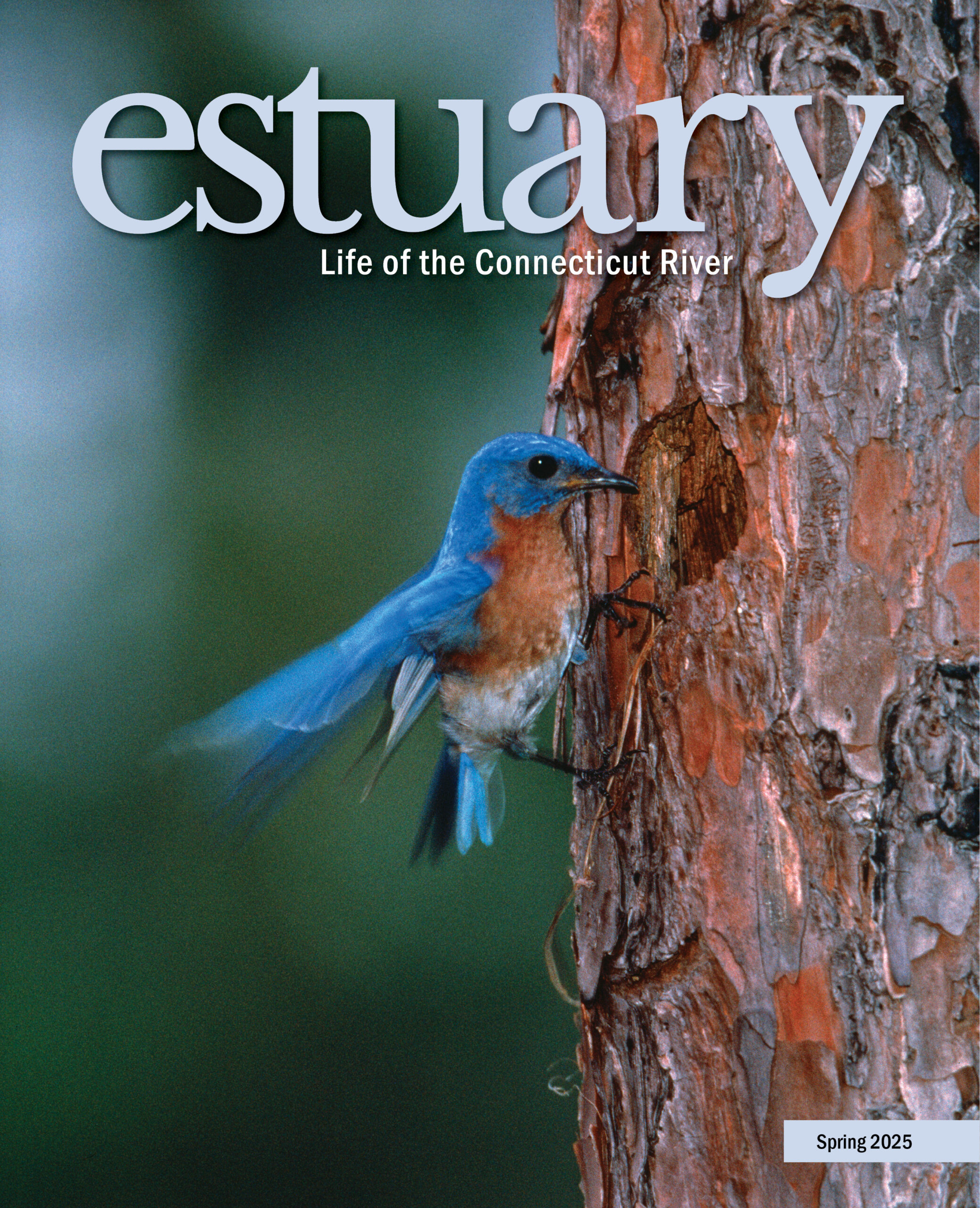

Chester Elementary School students gather around their teacher, Hilary Clark, watching the eggs she poured

into the refrigerated tank settle to the bottom. The eggs arrived in the orange jug to the right of the tank.

Giving Tanks for Aquatic Education

Story and Photos by Steve Gephard and Sally Harold

We often lament that the carefree days of exploring outdoors with only a dinner bell to call you home are unfamiliar to today’s children. But early learning about the natural world is important. It keeps us grounded in facts, comfortable with science, and able to participate in responsible decision-making about the environment. Environmental education develops a critical understanding of how the natural world works, and that’s particularly important for young folks who will inherit the awesome task of safeguarding the health of our lands and waters.

An environmental educational program we’d like to showcase is the Salmon-in-Schools (SIS) program co-sponsored by the Connecticut River Salmon Association (CRSA) and the Fisheries Division of the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CTDEEP). During its thirty-year history, this award-winning program has reached thousands of students, teaching them not only about the biology of Atlantic salmon but also about stream ecology and habitat, basic metabolic processes, and even basic mathematical modelling. The core of SIS is the care of salmon, beginning with live salmon eggs and ending with the release of tiny salmon into designated Connecticut rivers.

The program began in 1995 when CTDEEP was involved in an interstate program to restore native Atlantic salmon to the Connecticut River. Dams had extirpated the species in the first decade of the 1800s. CTDEEP had dedicated its Kensington State Fish Hatchery (Berlin, Connecticut) to the raising of young salmon for restocking suitable tributaries of the Connecticut River. The hatchery annually spawned captive adult salmon (offspring of salmon that had returned from sea to the river) and produced hundreds of thousands of eggs. Meanwhile, CRSA, a nonprofit conservation organization that was committed to the restoration of salmon, sought to build public support for the program. It learned of an educational program in Canada that brought salmon eggs into classrooms and approached the CTDEEP about duplicating the program in Connecticut. CTDEEP supported the idea but lacked the staff to fully implement it.

Collaboration with CRSA resulted in the SIS program. CTDEEP provides the eggs from its hatchery and technical support, and CRSA interfaces with schools and runs the program, which includes teacher training, assistance with curriculum, and distribution of teaching aides such as maps and photographs. Even with the termination of the salmon restoration program in 2012, the school program continues, thanks to CTDEEP’s continuing Atlantic Salmon Legacy Program. The program began in 1995 with one school in North Haven, Connecticut, but now fifty to fifty-five schools participate annually (currently the program is only available in Connecticut).

The program, available to classes at the elementary, middle, and high school levels, starts when a teacher signs up with CRSA at the beginning of the new academic year in September. Participating teachers attend an orientation session in October where they are taught by CRSA members and CTDEEP biologists. They learn about the salmon’s life history, receive training on assembling and operating their special tanks, and are provided with the general information they’ll need to guide their students through the program.

In nature, adult salmon lay their eggs in gravelly streambeds in late October, and the eggs lie buried in that gravel all winter long, experiencing water temperatures as low as 33 degrees. The only way to maintain such cold water in a classroom is to use a fish tank that has a special water chiller. These tanks are heavily insulated with Styrofoam and are equipped with an aerator to keep the oxygen in the water at suitable levels. Each classroom sets up one of these specialized tanks for the fertilized salmon eggs that will be delivered from the Kensington hatchery via an insulated picnic jug in early January. When they are received, the eggs are poured gently into the tank where they settle into the gravel layer at the bottom. There they sit for the next couple of months, incubating, until they hatch and the tiny fish are ready for students to release them into a designated river. But there’s more to the process than simply watching and waiting.

Atlantic salmon is a cold-blooded animal, which means that its metabolism and the rate of its development from an egg to a freshly-hatched salmon, called a “fry,” is dependent on the water temperature. If the water is warm, the eggs will develop and hatch quickly. If the water is cold, that process proceeds slowly. In nature, it is critical for wild salmon fry to emerge from the gravelly stream bottom at the same time that aquatic insects are also emerging after their winter hiatus—it is those insects on which the salmon fry feed. Students must carefully simulate this timing. Stocked too soon, the fry would starve because there would be no food for them in Connecticut streams. Stocked too late, the fry will be close to starvation and will not survive. Salmon fry are notoriously hard to feed on artificial food in a classroom setting, so the students’ fry are not fed and must be released soon after they hatch before they starve. The strategy is to manipulate the water temperature to time hatching during a critical window in April or May when there is plenty of natural food in the river to sustain the young salmon.

Years ago, scientists developed a “Developmental Index” (DI) that correlated water temperature to a percentage of egg development. At 33 degrees the egg achieves in one day about 0.3 percent of the total development it needs to hatch and begin feeding. In one day at 50 degrees, the egg achieves 1.2 percent of the total development. This relationship is known for every degree of temperature in-between and can be programmed into a spreadsheet. If the water temperature for each day is known, the students can predict when the eggs will hatch. Importantly, if their initial projected hatch date is too early or occurs during a school holiday, the water temperature can be changed in advance to target a specific date for hatch and stock-out. When the eggs are delivered, the students are told where the eggs are in their development (usually about 50 percent). They then monitor and control the water temperature in their tank to reach a desired hatch date.

Pale orange salmon eggs settled in among the gravel on the bottom of Chester Elementary School’s salmon tank.

This is a great educational experience for the students, coupled with the fun of watching these little fish develop. While the eggs develop, the SIS curriculum teaches the students all about salmon: where they were found historically, where they are found now, the challenges (such as dams) they confront during their life cycle, and approaches scientists use to manage, conserve, and restore their populations.

Salmon can be used as a surrogate for so many species, including native trout. Each teacher may customize the study plan for their class. One elementary school Spanish teacher used the program to teach students environmental science and salmon-related Spanish vocabulary. A math teacher taught the students how to record their data observations on spreadsheets the students created on the computer.

Last January, we helped deliver eggs to Hilary Clark’s 4th Grade Class in Chester, Connecticut, and were impressed by the level of preparation and enthusiasm exhibited by the students. Everyone in the school knew that the eggs were arriving that day. The students took turns peering into the fish tank and giggling at the sight of two little black dots on each of the eggs—the future eyes of the little fish.

Last May, we met Hope Tolland’s class from Tyl Middle School in Montville, Connecticut, along the Salmon River in East Hampton, Connecticut, for stocking day. Using red plastic cups, the students took turns releasing small numbers of salmon fry into the shallow edges of the river.

Teacher Hope Tolland looks on as her students from Tyl Middle School release their tiny salmon fry into the Salmon River in East Hampton, CT. The fry were distributed between many red cups so that all students had a chance to release some.

But there was more to the day than releasing fish. Hope and her colleagues created scavenger hunts in the state forest that lines the river, challenging the students to look for trees, bugs, plants, and birds. The students were also quizzed about what makes the Salmon River good salmon habitat, drawing upon their lessons from over the winter. It was a suitable climax to the program that began five months earlier.

CRSA and CTDEEP are to be commended for this effective educational program. We are impressed by the many talented and dedicated teachers who are committed to this program and continue to reach many students, year after year. After thirty years, we now have participating teachers who were once in the program as students! Connecticut schools that wish to be considered for the 2025–2026 program should contact CRSA at salmoninschools@ctriversalmon.org by early September 2025.

Steve Gephard is a fish biologist who retired from the CTDEEP and has a long association with the Connecticut River. Sally Harold has worked on dam removal and fish passage projects for over twenty years, including as Director of River Restoration and Fish Passage for the Connecticut Chapter of The Nature Conservancy. Steve and Sally collaborate on dam removals and fishway projects through RiverWork, LLC, and can be reached at Riverworkllc@gmail.com.