This article appears in the Winter 2024 issue

This article appears in the Winter 2024 issue

Hydrilla: Lovely aquarium plant or dreaded invasive plant that is killing commerce? Image Credits: Getty Images/hiindy22 (Hydrilla).

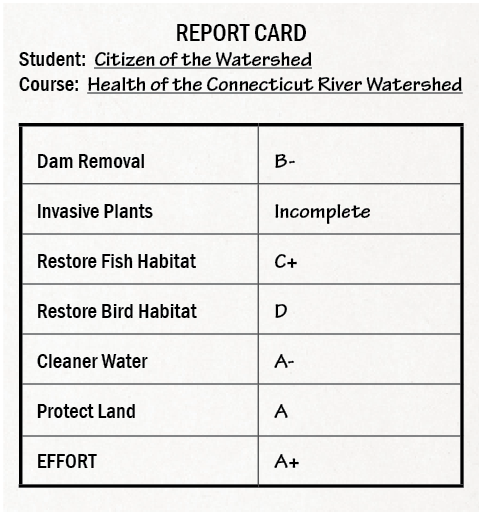

Forty years ago, the waters of the Connecticut River were vastly improved, mainly through teeth exerted by the Environmental Protection Agency (among many others) on flagrant polluters. Political pressure came from dozens of land trusts and other environmentally-motivated nonprofits created a decade earlier—for which fiftieth anniversaries in the past couple of years abound. Thousands of volunteers joined in the environmental efforts.

Meanwhile those with a casual interest and concern for our environment, but not so much “in the know,” may have relaxed and told themselves that the problems of their (our) river and watershed were resolved. So many advances have been made that one can be forgiven for thinking that the worst is behind us. Unfortunately, in addition to old problems that have been assessed and quantified, new problems have arisen.

Today it’s unclear to me if the watershed is in demonstrably better shape than it was in 1985.

Climate change, mainly in the form of rising temperatures, is largely to blame, perhaps more than we even know today, for threatening continued progress. Climate change-induced rising sea levels are a problem for the longer term, but changing weather patterns are a major factor today.

The rains in Vermont in July 2023 caused major damage throughout the state and sent tons of sediment downstream. Many towns in our watershed have also suffered material erosion and washouts that have exposed deficiencies in culverts throughout the watershed. By one estimate, there are 2,000 to 3,000 culverts in the watershed that are now deficient; the total cost to bring these culverts up to speed may amount to several billions of dollars.

Rising temperatures in river waters are destroying habitats important to fish. We haven’t seen a correlation between water temperature and the invasions of invasive plants, but regardless, non-native invasive plants are clogging our harbors as well as our paddling and fishing areas.

Some “old” problems are exacerbated by climate change. We are seeing more of the so-called Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs) whereby rainwater and sewage go down the same pipes into treatment plants; when overwhelmed by torrential rains, sewage and rainwater are redirected into the river.

Some “old” problems never seem to go away. We continue to see farms leaching chemicals into our river and its tributaries and forests being clear-cut to make way for private homes and businesses.

Frightening to many of us is the well-documented decline in bird population in North America, from 9 billion in 1970 to some 6 billion today. This loss is attributed mainly to loss of habitat; even if we could reconstitute the habitats of yore, would the birds return?

There is some good news and new strategies underway. Volunteers and organizations like the Connecticut River Conservancy (CRC) are planting tens of thousands of trees along with erosion-resisting riparian (riverbank) plantings. CRC is removing several unnecessary dams each year…with several thousand to go. Each dam removal frees upriver habitat for important fish and plants and restores healthy oxygen into our waters.

There is movement to reduce CSOs. The Metropolitan District Commission (MDC) in Connecticut is completing a tunnel four miles long and eighteen feet in diameter to provide a temporary “holding tank” when excessive rainfall creates combined storm and sewer overflows (see “Below the Surface,” Fall 2024.). This will enable MDC to calibrate flows into the treatment plants long after the rains stop. Springfield, Chicopee, and Holyoke (Massachusetts) are working on solving the same problem in those cities (see Bill Hobbs’s story in the Spring 2025 issue).

Pollinator gardens and other bird habitat restoration efforts are on the rise; is there a way to multiply these efforts?

Fish (including lamprey and eels) are climbing up fish ladders or riding elevators up and over certain dams and are being counted. Some important numbers are improving.

Scientists, especially those with the US Army Corps of Engineers (COE), are trying to halt and reverse the incursion of hydrilla, a cute little plant many of us purchased for our little aquarium many years ago, which, when pulled, may break off into pieces that flow downstream and re-propagate in other wetlands and waterways. Though boaters have long been encouraged to wash off their boats and trailers when going from one waterway to another, it hasn’t been enough. The COE is now testing for which herbicides or other approaches will best curb hydrilla. By contrast, the equally-invasive water chestnut can simply be ripped up by its roots and destroyed, and organizations like CRC and Friends of Whalebone Cove regularly organize groups to paddle out and pull.

Another positive sign is that roughly 25 percent of the land in the watershed is protected today by land trusts and easements, and that percentage is growing.

Another positive sign is that roughly 25 percent of the land in the watershed is protected today by land trusts and easements, and that percentage is growing.

It’s hard to set priorities and allocate resources to the various problems because we don’t know how to calculate their relative values and the relative costs to mitigate. How does one choose between removing a dam versus planting more trees?—or investing in a city’s facility to store combined sewage overflows versus protecting more land? In fact, we can’t afford to choose. We must do it all—and watch out for what’s coming. We’re fortunate that so many organizations are throwing their best minds and efforts against the problem and are collaborating. Your interest, support, and advocacy through one or more organizations is also critical. Thank you!

Dick Shriver

Publisher & Editor