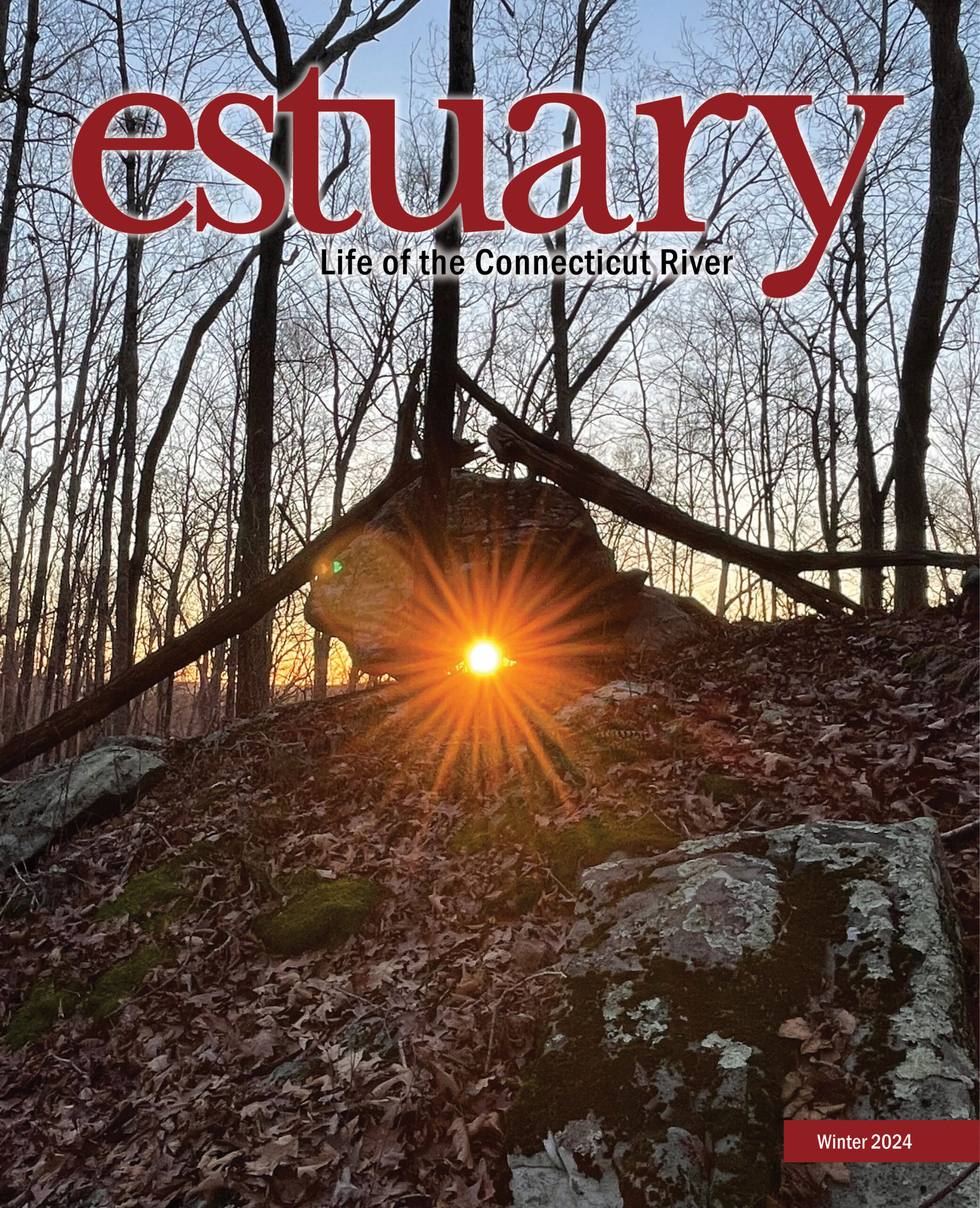

This article appears in the Winter 2024 issue

This article appears in the Winter 2024 issue

The Bow Bridge in Central Park, New York City, crossing over the Lake. Olmsted was Architect in Chief of Central Park. Image Credit: Getty Images/johnandersonphoto.

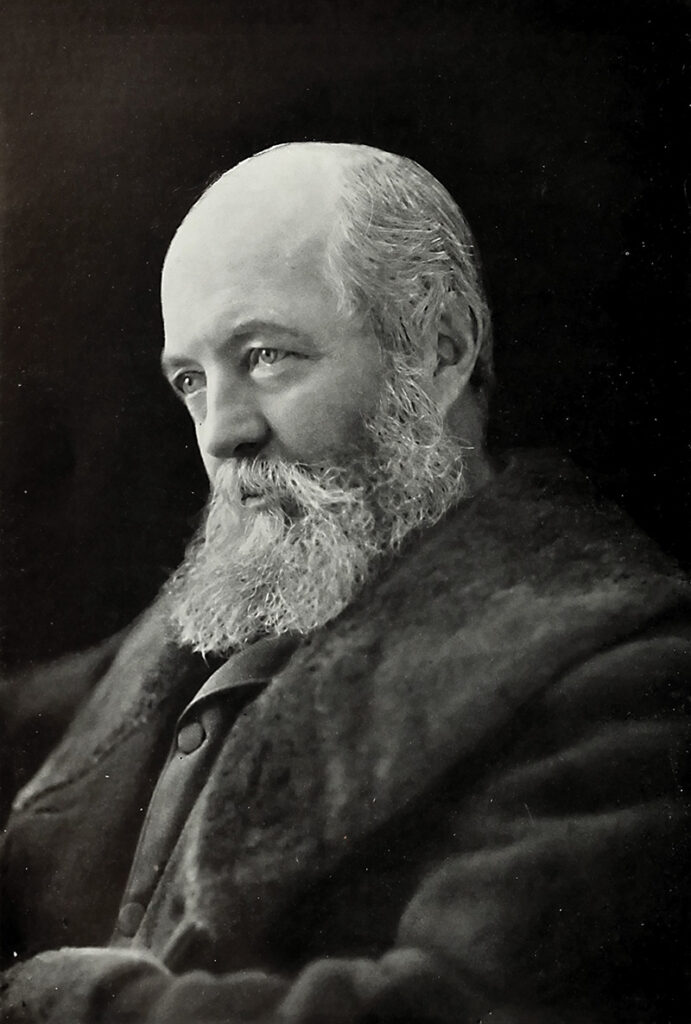

Mention the name Frederick Law Olmsted and many people will know him as the father of landscape architecture and the man who, with his partner Calvert Vaux, designed New York’s Central Park.

Mention that Olmsted was born in Hartford, Connecticut, and nearly as many are surprised. Add that he ascribed his taste for naturalistic landscapes to the tramping, horseback rambles, sailing, and swimming he enjoyed on and around the Connecticut River as a lad, and it’s news to the vast majority.

In 1893 he told Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer, our nation’s first woman architectural critic, “The root of all my good work is an early respect for, regard and enjoyment of scenery […] and extraordinary opportunities for cultivating susceptibility to the power of scenery.”

That same year, at a gala celebration for the World’s Columbian Exposition, Daniel Burnham, the driving force behind Chicago’s World’s Fair, praised Olmsted for his contributions to the fair and to landscape design: “An artist, he paints with lakes and wooded slopes; with lawns and banks and forest-covered hills; with mountain sides and ocean views.”

All true. But Olmsted’s path to brilliance was as meandering as the paths he designed for his parks, campuses, and other projects.

Olmsted was born in 1822 to John and Charlotte Olmsted. His father was the scion of several generations of Connecticut Yankees and a prosperous dry goods merchant who took a lively interest in nature and the exploration thereof. He frequently took Fred, as he was known, and his younger son, John Hull Olmsted, on horseback treks through the woods and fields that surrounded Hartford, sometimes stopping at a stream where the boys could swim. Fred learned to sail at the mouth of the Connecticut River while visiting relatives. Later John gave the boys a boat they sailed all the way from Hartford to Long Island Sound. Startlingly, when Fred was nine and John only six, their father allowed them to walk unaccompanied from Hartford to Cheshire, a distance that required them to find and spend a night in a roadside tavern where they sank into sleep after wolfing down a substantial dinner.

Frederick Law Olmsted, 1893.

Fred was a serial enthusiast about whatever captured his fancy, but he was a lousy student. He was “mis-educated,” by his own telling, at “dame” schools—the precursors of nursery schools—and then under the tutelage of a series of impoverished country parsons who took in young boys to raise a few extra dollars. His first such teacher, Reverend Zolva Whitmore, inculcated in him a love of flowers and gardening, along with planting the seeds of what would become Fred’s abolitionist views.

At another minister’s school, the students were allowed to go barefoot except for during Sunday services. Fred took full advantage of the lax supervision by setting out on solitary wanders through the countryside, chasing rabbits, and rigging traps in hopes of catching quail. Occasionally he stopped at the local country store to buy sweets and listen to the old men gathered around the inevitable potbellied stove. “Every house, every room, every barn and stable, every shop, every road and highway, every field, orchard, and garden was not only open to me but I was everywhere welcome,” he wrote.

When at home in Hartford, he extended his self-education by prowling the city’s library and exploring his grandmother’s book collection. Among the latter, he discovered and consumed such volumes as William Gilpin’s seminal work, Remarks on Forest Scenery (1791), and Sir Uvedale Price’s Essay on the Picturesque, as Compared with the Sublime and the Beautiful (1796).

But, as Olmsted later wrote, “I was very active, imaginative, impulsive, enterprising, trustful, and heedless. This made what is generally called a troublesome and mischievous boy.” His loving yet worried father pretty much agreed, urging his obviously intelligent firstborn son to find focus and purpose as he approached age fourteen, then an age at which lads were expected to become men.

Fate intervened in the form of a much-too-close encounter with poison sumac which infected his eyes, seriously impairing his vision. His father took him to New York, where a specialist recommended “hydrotherapy”—meaning saltwater bathing. Fred spent three months in Saybrook, Connecticut, under the supervision of a Rev. G. C. N. Eastman, swimming in the Connecticut River estuary, and gradually regained his vision. But the illness scuttled his hopes to enroll at Yale. He was done with formal schooling.

What followed was a twenty-two-year odyssey of jobs and adventures and many, many romances—though no marriage resulted, despite Fred’s fond wishes. Among his efforts to find himself, he apprenticed as a surveyor and clerked with a New York importer of European dry goods. He attended classes at Yale where his brother was studying medicine and where Fred formed some of the most important friendships of his life, among them Charles Brace. Fred apprenticed as a seaman from New York to Canton, China, and back aboard the bark Ronaldson. He tried his hand at farming on his Uncle Brooks’s farm in Cheshire, Connecticut, and, for a summer, on a farm in Waterbury, Connecticut. He spent a few months studying farming in Syracuse, New York, and launched a “scientific” farm—purchased for him by his father at Sachem’s Head on Long Island Sound in Guilford, Connecticut. When that farm proved too small for commercial farming, his father bought it back from him, and Fred moved to a larger farm on Staten Island, New York, where he started over as a farmer-nurseryman determined to demonstrate the latest, best practices in an America that was still a predominantly agricultural society.

Then, in 1850, Olmsted sailed to England with his brother and Charles Brace for a walking tour. It was a seminal moment in his life, though it wouldn’t bear fruit for another eight years. His mission was to observe British farming practices, which were far ahead of those back home, particularly in the realm of agricultural technology.

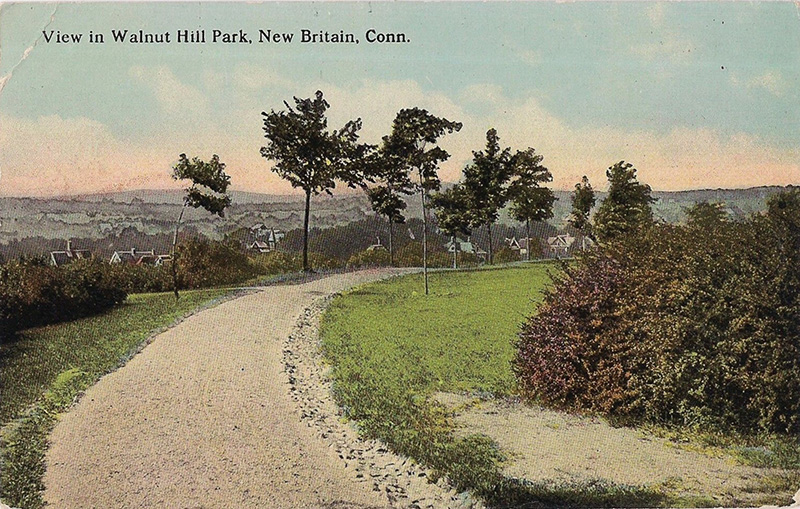

Walnut Hill Park, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, New Britain, CT. Image Credit: John Phelan, Wikimedia Commons

After landing at Liverpool, the trio kicked around town for a few days before starting out for model farms to whose proprietors Fred had letters of introduction. At a bakery where the three bought breakfast buns, the baker urged them to see Birkenhead Park, the pride of the city. It had opened just three years earlier and was the first park in Britain built with public funds. At 120 acres, it was bisected by a gently curving street. There were no formal plantings, no straight lines. Instead, clumps of trees, rolling meadows, picturesque ponds, and meandering footpaths dominated the scene. Yet the entire vista was man-made. “Gardening here,” Olmsted wrote, “had reached a perfection I had never known.”

Olmsted was impressed, in part, by the irony that, in democratic America, there was nothing comparable to what he called the “People’s Park.” “I was glad to observe that the privileges of the garden were enjoyed about equally by all classes. There were some who were attended by servants […] but a large proportion were of the common ranks, and a few women with children, or suffering from ill health, were evidently the wives of very humble laborers.”

Postcard, Walnut Hill Park, New Britain, CT. Frederick Law Olmsted designed Walnut Hill Park, one of his major commissions in Connecticut.

Those words appeared in Olmsted’s first book, Walks and Talks by an American Farmer in England. He wrote it on his return to farming on Staten Island. It was published in 1852 to some acclaim. At last, the strands of his earlier life were starting to come together.

But first there was yet another byroad yet to travel: journalism.

The success of Walks and Talks by an American Farmer introduced Olmsted to the publishing world. But, on the rebound from a broken engagement, he shifted professional gears once again, and in 1853 set out on a tour through the slaveholding states of the South as a correspondent for what would become The New York Times. His findings, which consolidated his abolitionist views, were gathered into two collections: A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States, published in 1856, and A Journey through Texas, published in 1857. Both were well received critically but failed to find commercial success.

Olmsted invested his father’s money in the publishing firm, Miller & Curtis, but the firm was forced into bankruptcy at the beginning of the Panic of 1857. By then Olmsted had left the firm, but allowed it to keep his father’s money as a loan. This put him at risk of being held liable for its debts.

With the Staten Island farm leased to a tenant, and his father and brother in Europe, Olmsted felt unmoored. He took refuge at an inn overlooking New Haven’s harbor, there to face alone both financial ruin and familial disgrace.

A chance encounter in the inn’s dining room made him aware of the political struggle going on in the newly created Board of Commissioners of the yet-to-be-built Central Park in New York City. The idea of a large—800-plus acre—park had been proposed six years earlier. Now, his interlocutor told him, the board was looking for a superintendent, and he urged Olmsted to apply for the job. Suddenly a solution to his financial woes was within reach.

The rest is history, as they say. Olmsted was appointed Superintendent. At the invitation of Calvert Vaux, he collaborated on a proposed design for the park. In April 1858 Olmsted and Vaux were awarded First Prize for their plan. A month later Olmsted was appointed Architect in Chief of Central Park. At thirty-six he had finally found his calling.

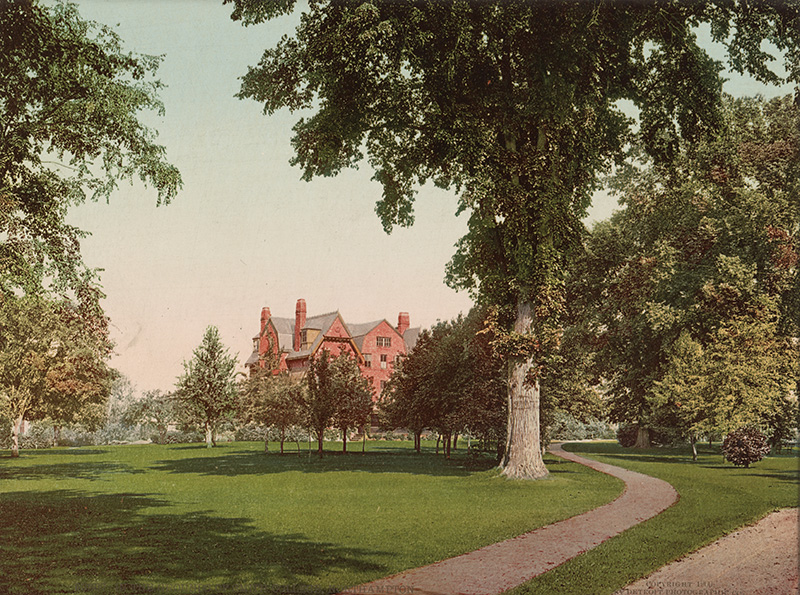

In 1891, Smith College, in Northampton, MA, hired Frederick Law Olmsted to turn its entire campus into an arboretum. Image Credit: Library of Congress

Today the park remains the jewel in the crown of Manhattan. But it was only the first of Olmsted’s many triumphs. In Connecticut alone he designed eight major projects, including New Britain’s Walnut Hill Park and Bridgeport’s Beardsley Park. Farther afield, among many other undertakings, he designed Acadia National Park and the campus of the University of Maine; the grounds of the US Capitol, the Jefferson Memorial, Washington Monument, and Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC; the grounds of the Vanderbilt mansion in Asheville and Duke University in Durham, North Carolina; the grounds of Amherst College, Phillips Academy, and Harvard University in Massachusetts; and the campus of Stanford University and the Palos Verdes Parkway in California. He played a crucial role in the preservation of Yosemite Valley as a National Park.

Altogether, these landscapes constitute an astonishing legacy. His concern for the commonweal and his determination to help shape an emerging America were constant. When he finally heeded the call of architectural landscaping, biographer Justin Martin wrote, “he brought the sum of all the wildly varied experiences that had come before. That’s why Olmsted’s work is so gorgeous, so dazzlingly set apart. It draws on the numerous disciplines to which he’d been exposed.” How lucky we are to continue to reap the benefits of the late-blooming genius of this son of the Connecticut River valley.

Janet Roach, a native of Old Lyme, Connecticut, knew by the time she was ten that she wanted to be a writer. She earned her first byline in The Day (formerly The New London Day) in 1965 and has been writing ever since.