This article appears in the Winter 2024 issue

This article appears in the Winter 2024 issue

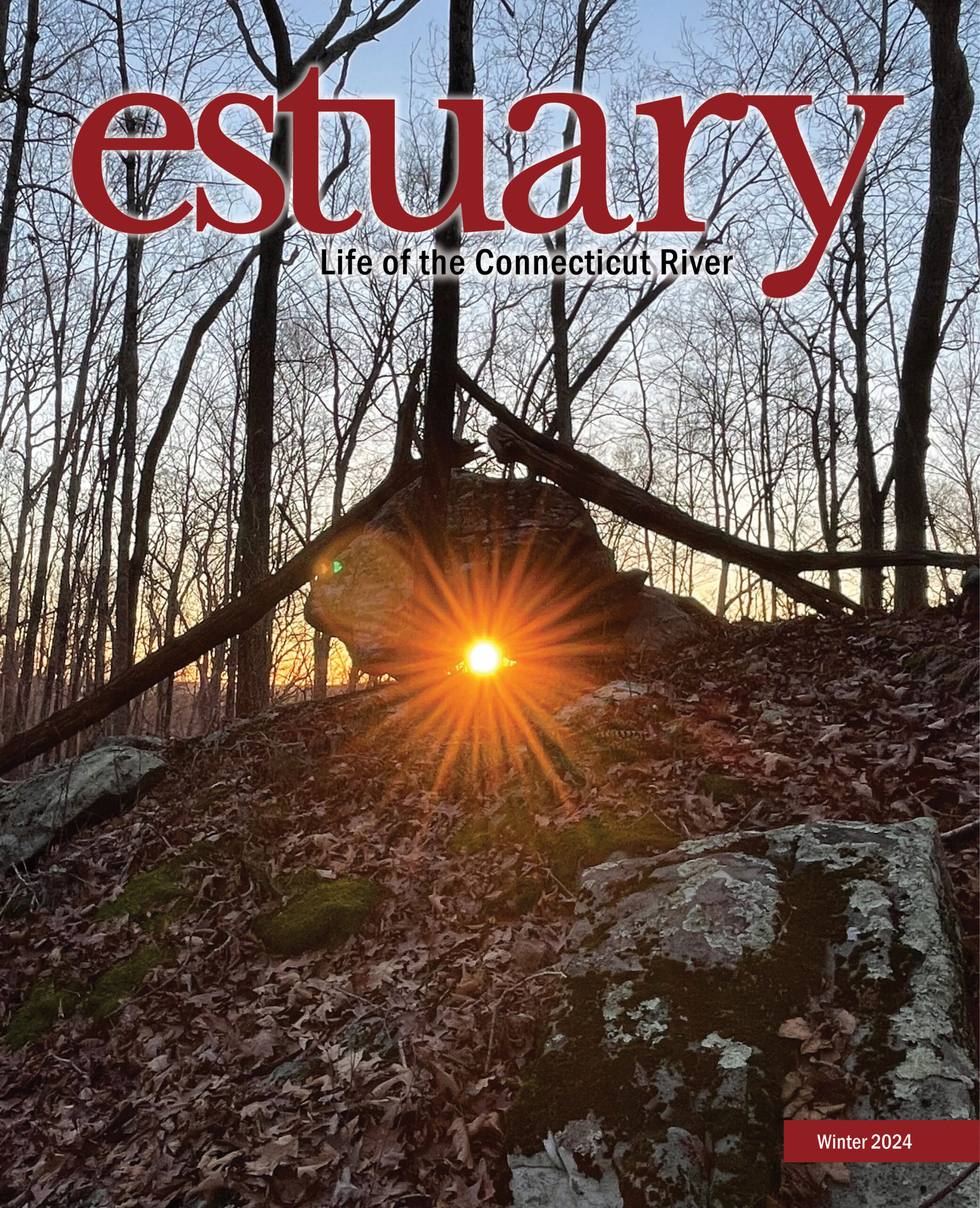

Biologist Jennifer Noll (far right) uses a water jet inserted inside a metal funnel to drive the funnel a couple of feet into the rocky streambed. A funnel to its left is ready to accept eggs. (L to R) Landis Hudson of Maine Rivers, Steve Gephard holding the water pump hose, technician Shannon Nelligan bringing egg jugs to the funnels, March 2024.

Plant Eggs to Grow Salmon

Story and Photos by Steve Gephard and Sally Harold

Below the water’s surface and even below the top of the streambed is the hyporheic zone. It consists of rocks of many different sizes between which water flows like an underground stream. As we wrote about in a previous column, this is a critical zone, and it’s where life begins for salmon and trout. A relatively new restoration strategy, which seems quite promising, involves the burying of salmon eggs into this hyporheic zone, which is what salmon do naturally. This practice is an alternative to stocking juvenile salmon that were raised in hatcheries, where the fish can pick up bad habits.

Paul Christman, a biologist with the Maine Department of Marine Resources, has pioneered this technique to create artificial “redds” (nests) in Maine streams. He takes Atlantic salmon eggs from a federal hatchery and buries them in streambeds in the late winter to early spring. (When Steve worked for the CTDEEP, he borrowed Paul’s equipment and buried salmon eggs in the Farmington River in Connecticut.) Currently, the only place we know of where this technique is being used for Atlantic salmon is in Maine. It’s part of the state-federal cooperative effort to recover the population of Gulf of Maine Atlantic salmon, which is listed as “endangered” under the federal Endangered Species Act, and it is the last remaining effort to save the species within the US.

A close-up view of salmon eggs.

When the two of us were invited this past March to help “plant” some eggs in the Sandy River, a headwater tributary of the Kennebec River north of Farmington, Maine, we jumped at the chance. We joined a team that included Paul’s colleague Jen Noll, Jen’s technician Shannon Nelligan, and Landis Hudson from Maine Rivers (a conservation organization).

Spring comes late to those parts, and although the daffodils were blooming along the lower Connecticut River, there was still snow to trudge through as we carried the equipment and eggs from the trucks down to the river. We were grateful that the ice had already gone out from the river. Jen explained that in many years, they have had to chop through ice to open up an area of streambed in which to plant the eggs!

The eggs came from the Green Lake National Fish Hatchery in Ellsworth, Maine, where there is a collection of adult salmon that are kept as broodstock. The salmon are spawned in October and there is a 48-hour period after fertilization during which the eggs may be handled, after which they become very sensitive to touch. (Transporting them after 48 hours could kill them.) After fertilization, the eggs are incubated in trays at the hatchery until they develop two tiny black eyes and are considered “eyed eggs.” At that point, they are resilient and can be safely moved and gently handled. On the day of our expedition, we transported 120,000 eyed eggs to the Sandy River to plant at four distinct sites.

Sally Harold pours a cup of salmon eggs into the water-filled funnel. After all eggs have been introduced, the funnel will be slowly pulled out, March 2024.

The equipment we carried into each stream site included a small water pump, a large hose, ten large (four-foot long) metal funnels, and a long steel pipe with handles at right angles to the pipe. The pipe fits onto the end of the water hose, which connects to the pump. At each site, we would unpack the gear, assemble the portable pump, attach the long steel pipe nozzle to the hose and anchor the water intake pipe in the river. Meanwhile, Shannon would carefully unpack the eyed eggs from a Styrofoam cooler that she carried in on her back and transfer them into plastic jugs filled with river water. We were planting the eggs in the type of habitat where wild salmon would naturally spawn. These areas had knee-deep water, often at the very tail-end of a pool or along a deeper portion of the downstream riffle, all with clean gravel and cobble ranging from marble-to-orange-size and with minimal amounts of sand and silt. There must be suitable gaps among the rocks to allow oxygenated water to flow through the hyporheic zone and bathe the salmon eggs throughout the remaining two months of their life as an egg.

The two of us took turns holding upright a custom-made funnel into which Jen would slide the metal waterjet nozzle. The funnel top was a wide aluminum cone that reduced down in size to a metal pipe end just slightly wider than the waterjet nozzle. Jen would press the waterjet nozzle through the end of the funnel pipe and into the streambed and with the high-pressure water blast, open a void among the rocks, working the nozzle like a jackhammer. As the water blast created an ever-deepening hole in the streambed, the funnel’s tip slid progressively deeper into the streambed until it was buried enough to stand upright. Jen would then extract the waterjet, take another funnel from us and repeat the process, burying up to 20 funnels per site in the flowing water.

Once a funnel was set, Shannon would approach with the jug of eggs and gently pour a cup of eggs into the top of the funnel and let them settle to the bottom of the funnel’s hole. She would then wiggle the funnel, pulling it up a couple of inches to let some surrounding gravel cave in on top of the subsurface eggs. Next, another half-cup of eggs was poured into the funnel and allowed to settle. The funnel was then slowly and gently pulled out of the streambed. The gravel surrounding the funnel tip would collapse over the eggs to bury them. An artificial salmon redd had been created, but the streambed looked undisturbed. About 1,200 eggs went into each redd, with a total of 30,000 at each of four sites.

As we moved between sites, we rotated assignments, giving us each a chance to pour in the eggs and dream about how these blueberry-sized orange spheres could become twelve-pound, thirty-two-inch adult salmon in four years. We were bundled for the cold except for our hands, which surprisingly did not go numb despite the water temperatures hovering just a bit above freezing. At the breaks during the six-hour day, we chatted, traded river and salmon stories, and learned more about each other’s backgrounds and journeys into conservation. Jen grew up along the Kennebec River, and while this column typically features stories of Connecticut River folks, it is a joy to share about others working hard to conserve and restore natural resources along their home rivers, just as we do along the Connecticut.

These eggs would hatch in a month or so, depending upon the spring’s water temperature. At that point, the larval fish are called alevin. They still have a big yolk sac bulging off of them and will stay buried in the gravel without feeding until the yolk sac is exhausted. Then, they wiggle up through the gravel and begin feeding on tiny aquatic insects. (These insects are also dependent on a healthy hyporheic zone.) Most alevin will be ready to migrate to the ocean in two years as a six-to-eight-inch “smolt.”

Maine data show that more smolts are produced from egg planting than from stocking hatchery-reared fry or parr. This is a valuable tool in the toolbox for recovering the endangered Atlantic salmon, and hopefully the practice can be expanded to other areas that have suitable habitat. Burying eggs on a cold March day to allow them to mature in the gravel of an upland stream is a lot more natural than feeding brown pellets to young salmon in a fiberglass tank in a hatchery that is a two-and-a-half-hour truck drive away from the river. When in doubt, mimic Mother Nature.

Disaster Strikes

The preceding text was written shortly after our March visit. Since then, we learned of catastrophic impact to this stretch of the Sandy River. Before our visit, the river had experienced severe flooding during one of the tremendous Maine winter storms, and parts of the adjacent town road and some homes were damaged. In response, a group of local residents (who own earth-moving equipment) and the Town of Phillips decided that they could “fix” the river so such damages would not recur. Without all the necessary permits and permissions, they entered the stream and excavated the streambed, lowering it about four or five feet and relocating it away from the road.

A view of the degraded stream, July 2024. The natural river channel, now dry, is to the left of the levee. The new channelized river is to the right of the levee about four or five feet lower and possessing few natural habitat features.

The enormous amount of gravel, cobbles, and boulders that their work generated was piled between the new channel and the road to create a huge levee intended to block floodwaters from the road. Their actions cut the river off from its natural channel and its floodplain. They removed all large boulders, wood structures (natural features from the riparian forest that provide important habitat), and straightened the riverbanks (see accompanying photos). In effect they lobotomized an entire mile of the river.

Steve returned to the scene of the crime in July 2024 to witness the damage and snorkel to assess underwater conditions. While we were encouraged that the artificial redds created in March were not touched (a short distance upstream), we were aghast to learn five natural redds created by wild salmon (a precious resource) and an estimated 17,500 wild salmon eggs were destroyed.

The people who did this are going to be held accountable, but as the established penalty under the Endangered Species Act for salmon is $20,000 per egg; a total penalty of $35 million is clearly beyond the ability of the small town and the bulldozer operators’ ability to pay. Currently, state and federal agencies are pulling together a team to develop a plan for stream restoration, which will cost many millions of dollars beyond the penalty and take years to complete. Snorkeling revealed to us that this stream possesses some of the best Atlantic salmon habitat in the US. The destruction of this habitat is a tragedy and a major setback to the effort to recover Atlantic salmon.

But there is a cautionary tale here, too. A very similar thing happened in the Connecticut River in 2011 after Tropical Storm/Hurricane Irene inflicted severe damage in our watershed, especially in the White River (Vermont) and Deerfield River (Massachusetts) drainages. The states wanted to see the severed highways restored as soon as possible and ordered equipment into the streams without detailed plans or guidance. The result was similar to what happened to the Sandy River. When the dust settled, the states had to spend an enormous amount of money to restore the streams and their habitat.

Jennifer Noll stands on the landward side of the illegally-created rock levee intended to protect the town road, Phillips, ME, July 2024.

Such devastating floods are bound to become more frequent and more severe. Damage to infrastructure such as bridges, roads, and homes built too close to the river is inevitable. In the days after floods, there is often no time to develop restoration plans and guidance, which will lead to more ill-conceived repair jobs and damage to habitat.

State agencies should develop emergency contingency plans now to tell contractors what they can and cannot do as they hurry to repair damages and restore access and connectivity for people. Helpful guidance should include: try to maintain the same stream channel geometry and elevation, don’t remove boulders and log jams needlessly, and don’t clear cut river banks. We also might consider proactively relocating structures and roads that are currently in the river’s floodplain.

Steve Gephard is a fish biologist recently retired from the CT DEEP Fisheries Division. He is a US Commissioner to the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization.

Sally Harold worked on dam removal at The Nature Conservancy.