This article appears in the Winter 2024 issue

This article appears in the Winter 2024 issue

Bank Swallows. Getty Images/MikeLane45

Bank Swallows:

Living Along the River

A healthy river system isn’t static. The flow of a river changes dramatically over the course of a year. The tremendous energy of the spring freshet or a flood event will move boulders, rocks, and sediment to rearrange pools, riffles, and runs to new configurations. A river system like the Connecticut that flows through the soft sediment laid down over thousands of years meanders and moves around its floodplain. A healthy river system is dynamic and dramatic, and many river critters have evolved to live amidst this energy and change.

One of those river critters is the bank swallow, whose Latin name of Riparia riparia doubles down on this fellow’s connection to rivers. Readers of this magazine have followed the seasonal murmuration of the tree swallows that congregate by the hundreds of thousands in late summer at the mouth of the river in Old Lyme and Old Saybrook to rest and feed before their southern migration. The bank swallow does not attend that particular avian party. While it’s a social species that also nests in colonies, it seems to prefer smaller but still noticeable gatherings a bit farther upstream.

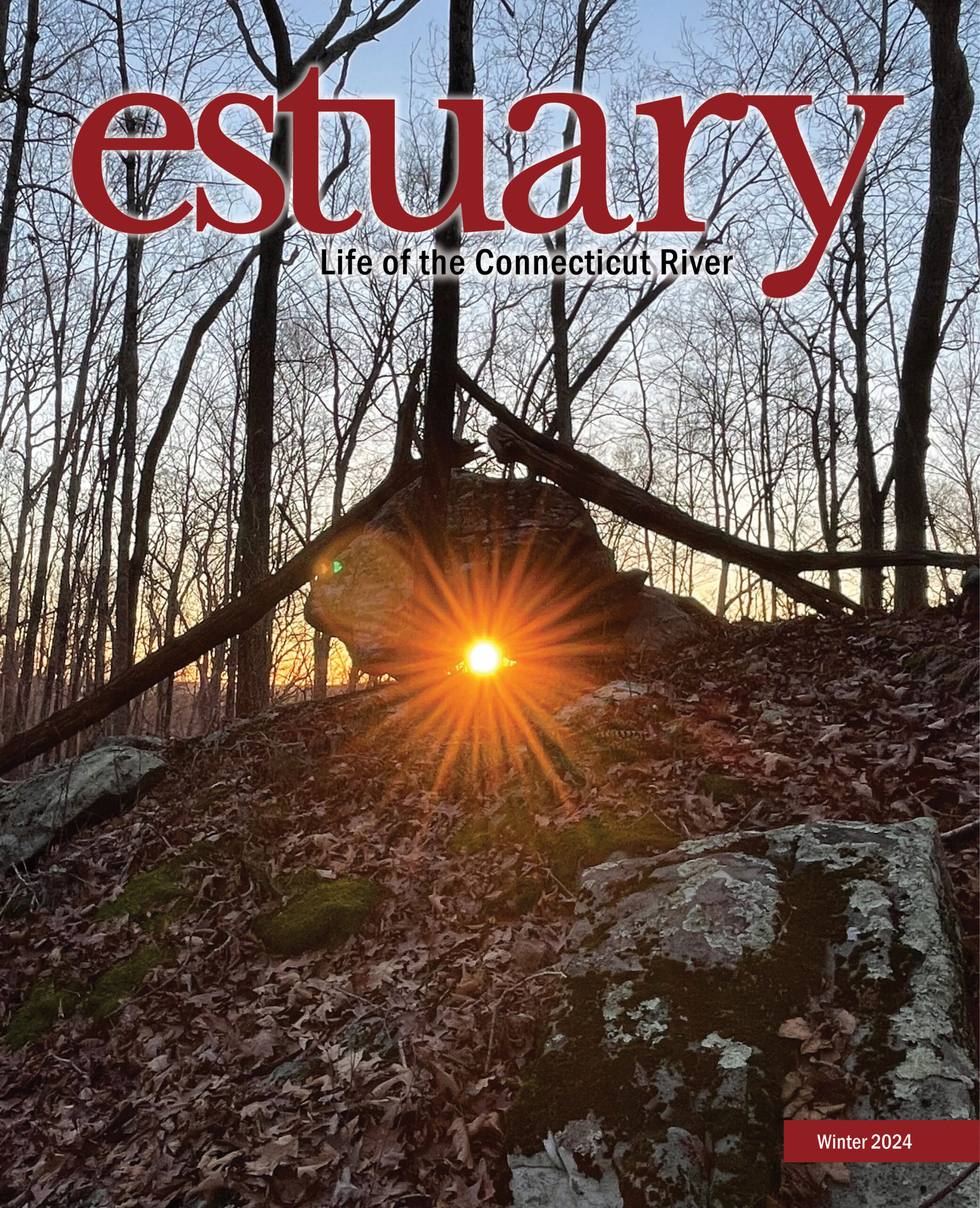

I spend a lot of time on the river north of Holyoke, including many special trips along the stretch of river between Lemington, Vermont, and Lancaster, New Hampshire. This stretch includes many miles of meanders, particularly in Maidstone and Guildhall. There are many places along the entire river to spot bank swallows, but I have had wonderful visits with these birds in this reach. The gradual bends and turns there are great places to spot bank swallows. The eroding banks created by the energy of water moving around the curve exposes the soft and friable alluvium that makes the Connecticut River valley soils so productive.

As you round a corner, it is easy to spot the dozens of small entrance holes to the bank swallow nests. And while the outside of river bends are always eroding, the inside bends will usually provide you a wonderful beach from which you can sit and watch the aerial ballet. At certain times of year if you watch the nests carefully, you can see the chicks waiting in the doorway for a food delivery from mom (or dad?).

The bank swallows have the characteristic angular wing and tail shape of the swallow family with a tawny coloration similar to many of their cousins. They are not as brightly colored as the blue-green of the tree swallow, but they are fetching enough, I say. If you have had a chance to stop and watch the bank swallows dart, swoop, dive, and swerve just over the surface of the water, you’ve seen these little birds in their glory. Their strength and grace in pursuit of one tiny insect after another is a humbling reminder of the effort these birds make to survive and thrive.

Images Credit: Andrew Fisk

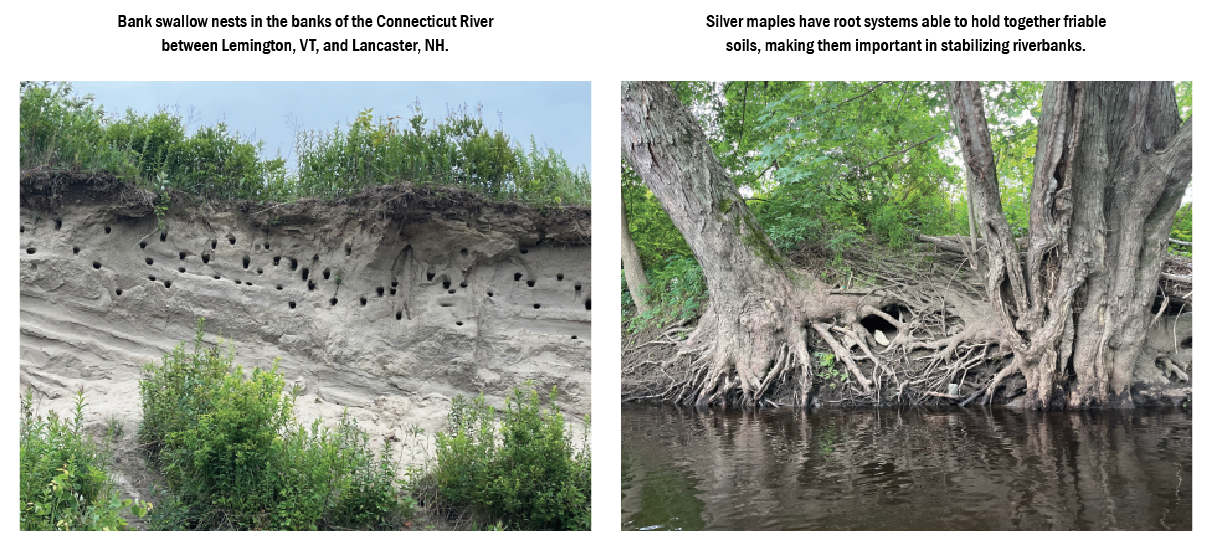

Bank swallows are found throughout North America, and the Connecticut River valley is within their breeding range. The experts say that the population is healthy, which is good news. Part of the reason for that healthy population is abundant riverine habitat along the banks of the river. That however is a good news/bad news story. While alluvial river systems like the Connecticut naturally erode and move and meander around their flood plains, humans have artificially increased bank swallow habitat by cutting down the bankside floodplain forests for agriculture, development, and views. The loss of riparian forests accelerates bank erosion—particularly through the loss of the majestic silver maples with root systems able to hold together our friable soils. So while bank swallows can easily adjust to an eroding bank by digging out a deeper or newer cavity, stabilizing eroding banks that eat away prime agricultural soils or eventually undermine houses and structures is not an easy fix. A healthy riparian forest allows a river to move at its own pace—which creates abundant natural bank swallow habitat and can protect human homes. These little birds with little brains have evolved to succeed with healthy riparian forests. With our big brains and creativity, we can too.

Here’s to the strength and dynamic energy of the bank swallow, a successful resident of our river valley. I pay homage to those same characteristics that I see in the many human residents working on behalf of the Connecticut River to make it a better place for everyone and everything.

Andrew Fisk, PhD, is the Northeast Regional Director for American Rivers. American Rivers is championing a national effort to protect and restore all rivers. Healthy rivers provide people and nature with clean, abundant water and natural habitat. For fifty years, American Rivers’s staff, supporters, and partners have shared a common belief: Life Depends on Rivers.