This article appears in the Fall 2024 issue

This article appears in the Fall 2024 issue

Elizabeth Mine

A New Life for a Vermont Superfund Site

By John Buck

There are few certainties in life. Death and taxes come to mind without argument. The certainty of change would have to be included, too, for Vermont’s Elizabeth Mine in Strafford.

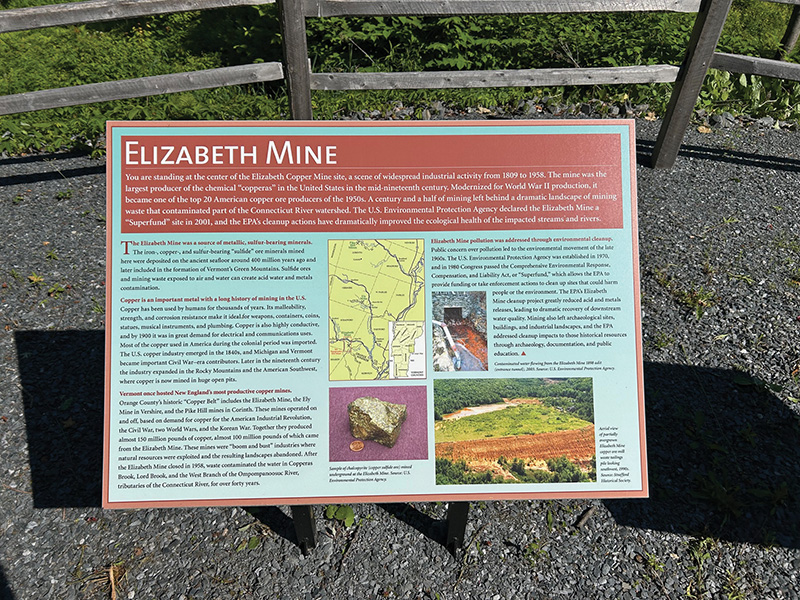

From pre-colonial virgin forest to copper ore discovery in 1789 by farmer John Taylor, to over 150 years of commercial copper extraction, to abandonment and toxic spoils leached into the Ompompanoosuc River (a tributary of the Connecticut River), to complete reclamation, the mine has undergone profoundly transformative changes.

Until one visits the reclaimed mining site it is difficult to picture twenty-first century Vermont, with its pastoral and forested landscape, as the one-time leading copper producer in the United States. In fact, due to its 150-year production history (until it closed in 1958), the Elizabeth Mine ranks among the top twenty copper sources in the US. That is no small measure given the extensive deposits still being mined in the western states.

Also notable are the patented mining innovations developed by Baltimore mining family-transplant Isaac Tyson made during the mine’s nineteeth-century transformation from copperas to full-fledged copper metal production. Tyson’s patent focused on the use of a blast furnace to create the temperatures required to fully extract the copper from the sulfur and rich iron ore. So enamored was he with this advancement and a strong supporter of innovation, President James Monroe made a special trip to Vermont in 1817 to view the process firsthand. The mine was also one of the first to utilize steam power to operate digging and transport equipment. Make no mistake, though, despite those advances and the economic and educational enrichments to the local community, human and animal power remained essential to profitable mine operation, with its physically demanding, dirty, and dangerous work for both.

Elizabeth Mine was operated as an open-faced mine from its inception until 1886. The copper ore was extracted by stripping away the trees and soil to expose the surface bedrock below. This approach created large swaths of denuded land. While not all of the mine’s land was exposed at one time, it eventually encompassed approximately 850 acres. Then, in 1887, horizontally drilled tunnels (adits) were incorporated. Thereafter, including the 1,370-foot-long Tyson Adit built in 1898, the mining company was able to access the extensive ore deposits well below ground level.

Modern deposit-estimating technology of 1909 measured the copper deposit seam to be up to 2 miles long, 600 feet deep, and as much as 64 feet wide. Despite the mine’s years of profitability and its extensive copper deposits, however, the company generally operated financially on the edge.

The ebbs and flows of the copper industry had forced the company to take out heavy loans during the down periods of the late nineteenth century. Repaying those debts with copper production was often hampered by the difficulty of obtaining quality smelting materials, expensive fuels, and unreliable transportation means. Many local railroads, such as the Lamoille Valley, Chelsea and Barre, and Central Vermont, laced Vermont at this time, but had not yet reached Strafford. Ten miles separated Strafford from the Boston and Maine-operated Pompanoosuc Station. Vermont, a long journey from most anywhere, remained that way until the construction of the interstate highway system of the 1960s and ‘70s. That meant shipments to and from the mine had to travel over the dirt roads of the day, an arduous effort under good conditions and nearly impossible during the extended spring mud season (Vermont’s so-called “fifth season”). With mounting debt and no realistic means to service it, compounded by low copper prices and fewer and fewer prospective buyers, the Tyson family, after nearly seventy years of ownership, closed the mine. It fell into receivership around 1904 and was purchased by New Jersey zinc magnate August Heckscher for $200,000 in 1906, considered a bargain even in those days.

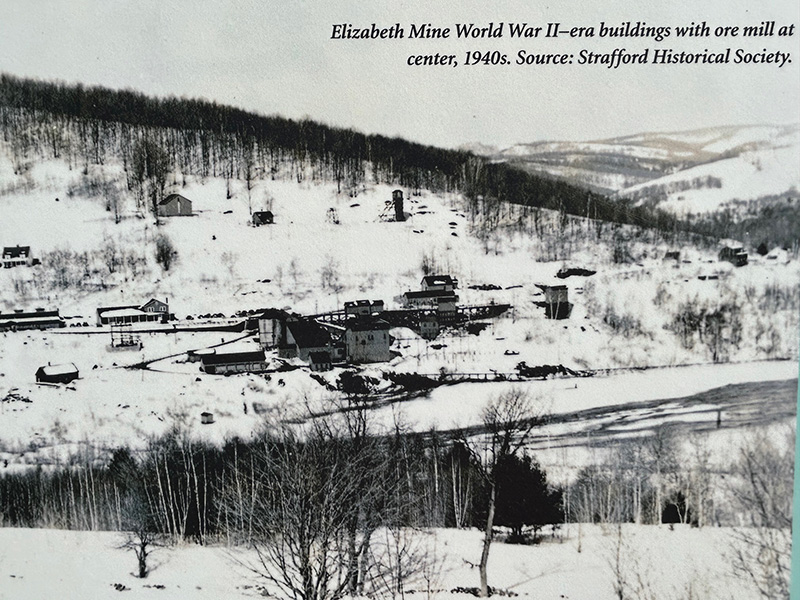

World events continued to influence the profitability of the mine in the early twentieth century. World War I put a high premium on copper, and the mine flourished until the Great Depression of the 1930s, only to be pulled back from the brink by World War II. The mine continued to produce significant amounts of copper well into the 1950s, but as world competition began to erode the mine’s profitability, the mine ceased operations for good. But that is only the first part of the story.

From Productive Mine to Superfund Site

History only recounts the successes and failures of the mine’s economic prowess and industrial innovations. What hadn’t been accounted for in any serious way until the end of the twentieth century was the operation’s waste by-products. Since the mine first began operation, it had been generating piles of earthen spoils (excavated soil and rock) and the sluiced residue, or tailings from ore extraction. This mine waste was transported by wheeled slag pots that could easily be handled by one man, and dumped near the mining operation. No thought was given to its impact on the surrounding environs. Eventually the extensive spoil piles and tailings, all infused with toxic metals and acids, began to percolate through the adjacent soils, eventually finding their way to wetlands and small surface waters, then to larger streams, and eventually to the west branch of the Ompompanoosuc River.

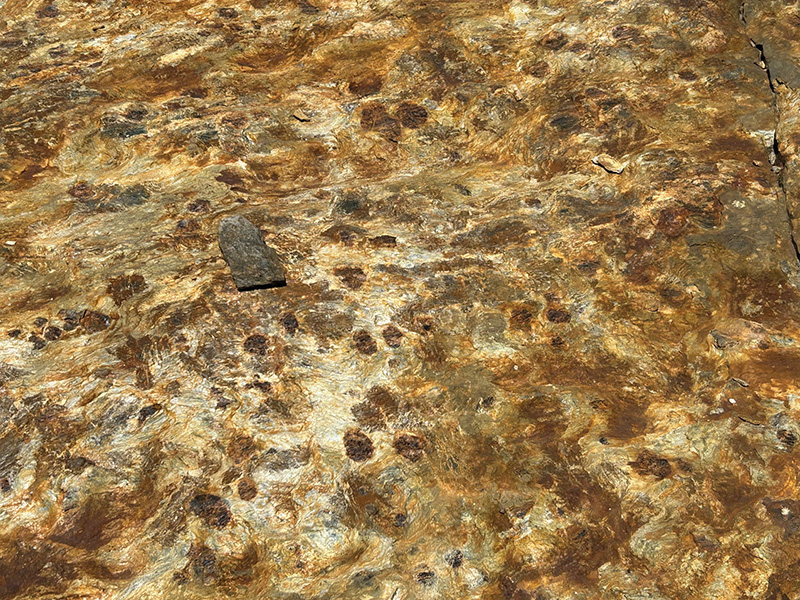

As the orange hue of the river became more and more evident throughout the latter part of the twentieth century, alarm bells went off, first among Strafford’s residents, then with state officials, and finally with the federal Environmental Protection Agency. Analysis of the contamination revealed toxicity levels well above scientifically-determined safe levels—so much so that the Elizabeth Mine was designated as a Superfund Site in 2001.

Superfund designation is reserved for only the most egregious environmental threats such as the infamous Love Canal of Niagara Falls, New York. This designation is only the first legal and administrative hurdle to cross, however, towards addressing the problem. Successful remediation—a daunting process—involves the efforts of local, state, and federal personnel to arrive at a solution that adequately removes the hazards presented by the mine, preserves the historic nature of the mine, and satisfies citizen concerns for the impacts of the cleanup itself, and only then is cleanup complete. All of this must be done within the financial capacity to do so.

Ten years after the Superfund designation, after years of back-and-forth negotiations among government and citizen stakeholders, revised cost estimates, and state and federal appropriation debates, mine reclamation began in 2011. Due to the environmental sensitivity, the extensive contamination, and overall complexity of the reclamation, the project wasn’t declared complete until 2022. The final cost of the project at $103,000,000—borne by the EPA—was four times greater than the original estimate.

The heart of the project includes 250 acres declared as a Superfund Site and within it the fortification of abandoned mine shafts, air vents, and a dam holding back 700,000 gallons of water. Also included are the stabilization of open bedrock cuts and reclamation of a contaminated eight-acre wetland. An important part of the remediation is the after-life monitoring by the State of Vermont at a cost of over $60,000 per year to ensure the project is having its intended result. Further adding to the after-life value of the reclamation and remediation is the installation of a 20,000-panel solar farm on the site that generates up to 8.7 million kilowatt-hours (kWh) per year, enough to power more than 1,300 homes.

Today the Ompompanoosuc River is running clear, and the Elizabeth Mine site is generating electricity every day the sun shines. Overlooking the site is a well-designed series of interpretative panels constructed in concert with the Strafford and Vermont historical societies. The educational site provides the viewer with a comprehensive 150-year timeline between the mine’s early beginnings through its expensive cleanup project.

While not explicitly stated, there are two messages that come across in the historical account. First is the enormous magnitude of what can be accomplished when diverse groups of people and governments work together for the common good. Second, and most important, is the notion that environmental quality and eventual reclamation of the land should be a priority incorporated within any production process when planning the original project. It is vastly more cost-effective to prevent contamination before it happens rather than face the untold costs of post-contamination cleanup.

John Buck is a retired state wildlife biologist living in Waterbury Center, Vermont. He runs the family’s 70-acre maple syrup farm along with his children and grandchildren.

Visit Elizabeth Mine

From Interstate 89, take Exit 2 and head east along State Highway 132 to the village of South Strafford. The mine is located just over two miles south of the village on Mine Road. There is a small parking area with excellent interpretive signs providing a good overview of the site.

To read an in-depth account of the profound economic, engineering, environmental, and social complexities related to the Elizabeth Mine, refer to Vermont’s Agency of Commerce and Community Development online publication, From Copperas to Cleanup, at https://accd.vermont.gov/document/copperas-cleanuppdf.

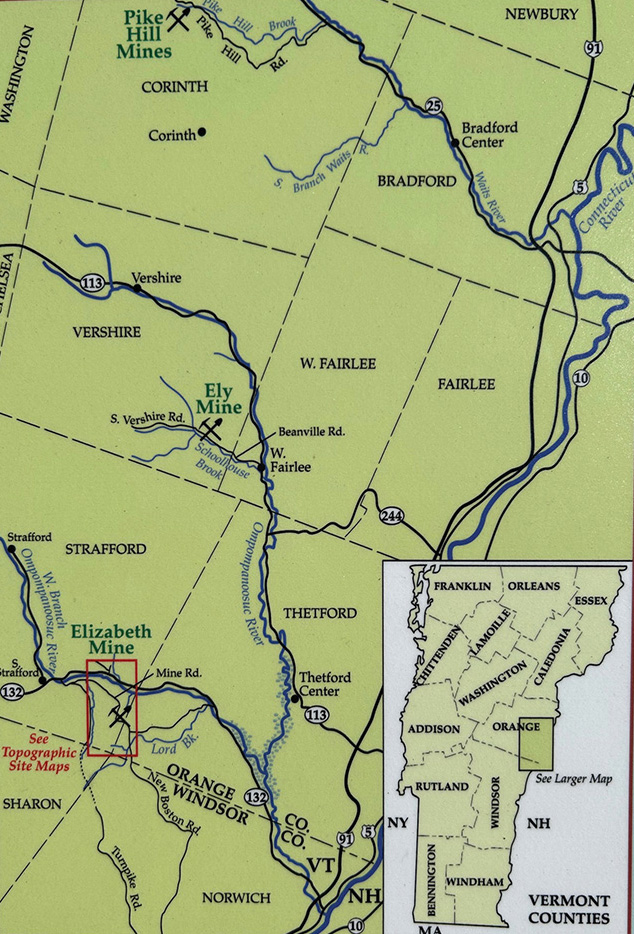

Map showing location of Elizabeth Mine Site.