This article appears in the Summer 2024 issue

This article appears in the Summer 2024 issue

On the afternoon of Essex’s Groundhog Day parade, figures walk through the misty streets, past clapboard houses and American flags, and gather in The Griswold Inn’s Wine Bar. They munch popcorn, sip wine, and await the popular art tour by owner Geoffrey Paul offered a few times every winter and spring. His fellow owners, brother Doug and sister-in-law Joan, mingle with the gathering crowd, greeting old friends and new alike. “We don’t think of ourselves as ‘owners’ of The Gris, but rather as caretakers of a unique and significant documentation of our history,” says Joan. “Of course, we also take great pride in offering a wonderful backdrop for our guests to celebrate life!”

On the afternoon of Essex’s Groundhog Day parade, figures walk through the misty streets, past clapboard houses and American flags, and gather in The Griswold Inn’s Wine Bar. They munch popcorn, sip wine, and await the popular art tour by owner Geoffrey Paul offered a few times every winter and spring. His fellow owners, brother Doug and sister-in-law Joan, mingle with the gathering crowd, greeting old friends and new alike. “We don’t think of ourselves as ‘owners’ of The Gris, but rather as caretakers of a unique and significant documentation of our history,” says Joan. “Of course, we also take great pride in offering a wonderful backdrop for our guests to celebrate life!”

Those guests come from all over the world, and this group is no different. One elderly sailor who moved back after decades in New Mexico says he missed the Connecticut River and in particular missed meeting people at The Griswold Inn. One couple who has just recently moved to Essex says they want to learn more about their new home. Another tells me that they took the tour already and are back for a second time.

Geoffrey arrives with his shock of thick white hair and casual blue pullover and thanks us all for coming. “You can take a picture of the main street in so many communities and see the same hotels and the same restaurants, and you can’t tell where it is,” he says. “There are those people who want that experience, who want to know what they’re getting. But thank goodness there are those of you who seek out special and unique places like this one.”

Covered Bridge Room at the Griswold Inn. Image Credit: Caryn Davis

The Griswold Inn is certainly unique—one of the oldest continuously operating inns in America, not resting for economic depression or civil war, serving colonial veterans and steamboat captains and rumrunners alike. The Paul family says that the recent pandemic was “tough,” tougher even than Prohibition, but in 2023 they celebrated the biggest year in the history of the inn. Indeed, for people like the ones here today, places like this have a renewed importance in the community.

“Inns were the centerpieces of every community in New England,” says Paul. “This was where ideas were exchanged, where politics were discussed, where gossip was shared. This was where people celebrated the birth of their children, their marriages, the deaths of their elders.” He pauses, looking around at all of us. “This is what we still do here today.”

The Griswold Inn in Essex, CT. Image credit: Robert Benson Photography

Another part of an inn’s task is to preserve and promote the local culture. The Griswold Inn displays hundreds of works of art and craft throughout the building: oil paintings, prints, advertisements, broadsides, bills of fare, artifacts from boats, antique firearms, and other ephemera. “We predate any historical society,” says Paul. “Let’s say you were an old colonial soldier; you’ve done your part to win independence and you had a relic that you treasure. There’s a good chance your kids don’t want it. You have no place to put it. So, you leave it to your bar.” What remains after more than two centuries is an accumulation of the culture of the town, the river, the state, and the nation.

The Lovell Family owned it from the 1880s to 1972 and collected much of this art, influenced in the mid-20th century by Thomas Stevens, the first director of the Mystic Seaport Museum and namesake of the library at the nearby Connecticut River Museum. And yet, Paul points out, even in the depths of the Depression, they never sold a piece. For the last two decades, the Paul family has added to it, curated it, finding nice pieces like a drawing by Norman Rockwell or a prized Antonio Jacobsen to match the existing collection.

The inn’s collection has three core components. The first is a wonderful set of locally-made guns predominantly from the Connecticut River Valley. Another is a compendium of ephemera, prints, and souvenirs from regional history. And the third, the “strength of this collection,” as Paul puts it, is what might be the largest and best privately-owned collection of steamboat art in America.

Antonio Jacobsen, Steamer “Connecticut,” Griswold Inn Collection, Paul Foundation, Essex, CT.

The history of the steamboat is intimately connected with this section of the Connecticut River. Born upstream in Windsor in 1743, John Fitch served in the Revolution and built the first steamboat in the country in 1787, operating it all summer on the Schuylkill River for the assembled state representatives at Philadelphia’s Constitutional Convention. Though he was granted a patent in 1791, Fitch himself failed to raise enough money to make steamboats popular and died in despair. Others took up the project, and by 1810 the first steamboat chugged its way up the Connecticut River, with regular cruises between Hartford and Middletown launching three years later. Everyone from the Marquis de Lafayette to Mark Twain enjoyed these magnificent Connecticut passenger vessels, until finally in 1931, they suspended service and never returned.

What has remained is the art. Paul begins his tour by showing us the steamboat mural behind the wine bar, painted in 1969 by local artist Aldis Brown, with its unique perspective out of the back of a boat, looking back at the town of Essex. He demonstrates the built-in device that rocks the large painting back and forth to provide the illusion of being on a ship.

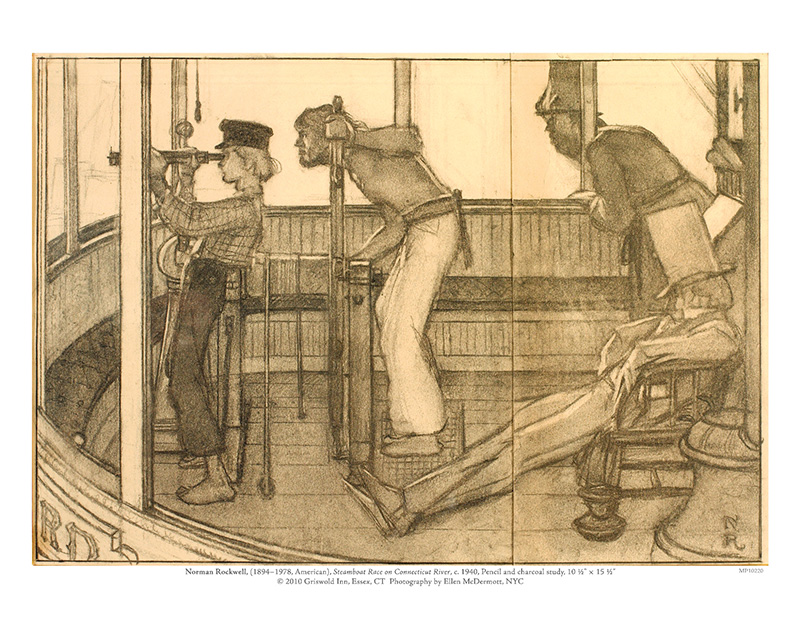

Norman Rockwell, Steamboat Race on the Connecticut, Griswold Inn Collection, Paul Foundation, Essex, CT.

On the wall next to the bar is a line drawing of four men on the deck of a steamer. “It’s a good little drawing,” Paul laughs. “It’s by a guy named Norman Rockwell.” Paul saw it at a marine art dealer in California, and when he heard the title, “Steamboat Race on the Connecticut,” he bought it immediately. The director of the Norman Rockwell Museum informed him that not only had it been a cover of the Saturday Evening Post, but it also told the story of an illegal steamboat race with an undercover agent from the United States Steamboat Inspection Service ready to bust the captain for putting the passengers at risk. Even more than that, the race it depicted took place just off Essex. “Well, this picture came home,” Paul says simply. “It belongs here.”

The oil painting rendered from that drawing was presumed destroyed in a fire, but a few years later it appeared on the cover of a Christie’s catalog with an estimate of over $1 million. Paul bid on it anyway, hoping it wouldn’t go that high, but instead it went even higher. “I sobered up after a few days,” says Paul, “and called Christie’s. ‘Can’t you tell me who bought it?’ I asked.” They did tell him because it was going to be exhibited in public by “two guys who don’t collect art.” “You would never have gotten this picture no matter what you did,” they told him, “because it was bought by Steven Spielberg and George Lucas for their Museum of Narrative Art.”

Artist Unknown, Challenge, Griswold Inn Collection, Paul Foundation, Essex, CT.

Paul moves from behind the bar and points to a valuable oil painting by Antonio Jacobsen, one of thirty at the inn, the largest collection in private hands in America. Jacobsen was born in Copenhagen in 1850 and emigrated to the United States in 1873, where his artistic abilities landed him a job painting ship portraits for the Old Dominion Steamship Company. He kept going, painting between 5,000 to 6,000 tugboats, sloops, and other ships, sometimes daily, recording almost every ship that docked in New York harbor between 1873 and 1919. That means he finished a painting every two days. “He was the Andy Warhol of his day,” says Paul. “Probably he did the body of the ship and others painted the water and sky and so on.”

Most of the oil paintings in the collection were commissions. “You’ve got to appreciate and understand how important artists were to the captains and owners of the vessels,” Paul continues. “Captains and owners were the only ones who could afford oil paintings, and when they would commission artists to paint the vessel, they called them portraits.”

He points out one nearby, a painting by James Bard, one of the folk-art Bard brothers, who painted almost 500 steamboats on the Hudson River. Some of those vessels also worked on the Connecticut, and when the Mariners Museum in Virginia deaccessioned one, Paul snapped it up. The rest are all owned by museums. The vessel in this painting was sent by Cornelius Vanderbilt to the Connecticut River to dominate the New York-to-Hartford run. For six decades Bard went to great effort to depict every steamboat to the last detail, even measuring the vessels by hand.

Antonio Jacobsen, Steamer “City of Worcester,”

Griswold Inn Collection, Paul Foundation, Essex, CT.

Paul then shows us two pen and ink drawings by Samuel Ward Stanton from the 1890s. Stanton’s family built steamboats, but he had an aptitude for art and liked drawing them instead. “He made it his mission to draw every single working steamboat in America in the 1880s and 1890s. The vessel in one of the prints, Saratoga, juxtaposes the giant vessel with a little sailboat. Another is depicted with the engineering marvel of the Statue of Liberty. By then, newer steamboats were more like floating palaces, forerunners of the great cruise ships of the 20th century. Stanton himself might have become one of the world’s most prolific steamboat artists, but the last vessel he sailed on happened to be the Titanic.

With more than a glint of pride in his eyes, Paul takes the group to what might be the jewel of the entire collection, what he calls the finest Jacobsen in existence, a portrait of the enormous steamer Connecticut in all its glory. At 383 feet long, the vessel held up to 1,500 passengers, and this three-quarter view in the original frame is a masterpiece even to untrained eyes. “There was no way I was going to let a museum get a hold of this just so they could keep it in the basement,” says Paul. “But the painting is more important than the vessel. Jacobsen did all this one himself, to show his skill as an artist. This was not something he was churning out for commercial purposes.” He pauses. “They believed that there was nothing man couldn’t do, and that’s what Jacobsen is illustrating with this picture.”

An hour into the lecture, we crowd onto the blue carpet of the lobby to see interior views of the Connecticut and the Middletown. Paul continues the story of more steamers and more paintings, of disasters on Long Island Sound and in the Connecticut River, of the origin of red lights on bridges because of a crash at the Middletown-Portland Bridge. He spends time on the intricacies of printmaking and mentions a copper vessel found in the ceiling of the inn, probably where the Lovells hid liquor during Prohibition.

We walk carefully through the evening crowd gathering in the epic Taproom, the oldest part of the inn, called by many one of the best bars in America, then into the Covered Bridge Room, which surely must rival it. There are few rooms in the world like this, and fewer in America, packed floor to ceiling with art and artifacts. It got its name not because of its unusual arched ceiling, but rather because the wood used to build it came from a local covered bridge. “If you collect American Marine art, and you believe in heaven, this is what it looks like,” Paul says, standing in front of the huge fireplace. “That’s not to say that each object in here is masterpiece quality. But each piece was acquired over many years and screwed into its own comfortable niche. You can’t replicate this. You can go to a museum and see the same pictures, but it’s in a more sterile environment. There’s something warm and captivating about the history that you’re surrounded with here.”

This room and much of the rest of the inn was preserved, ironically, by the Great Depression, when so many similar places were “renovated” or torn down. The Lovells never sold off the collection to pay their bills. “Poverty is what has preserved us,” says Paul. “And now, we are at risk of losing that history more than ever before.” These days, the danger is due to wealthy owners who may not even live in the area, or care about the history and culture of the place. “Luckily,” Paul continues. “The people that move here, for the most part, like the character of the place.”

It is a powerful experience to dine and drink at The Griswold Inn. It is even more powerful to discover what this cultural space means. As Paul takes his leave, he gives us one more directive. “Now that you’re experts,” he says firmly, “it’s your job to take this history out into the world, to educate and inspire.”

My wife and I retire to dinner just outside the Gun Room, near pistols by inventors Samuel Colt and Simeon North, and long rifles made in Hartford and Springfield. We slurp rich chowder and sip cocktails that would make the temperance crusaders shudder. Across from us is another steamboat painting and, experts now, we argue about its merits. Others from the tour sit nearby, all unofficial docents, ready to educate and inspire. A folk singer strums a guitar in the Taproom, singing a sad song about travel and home.

For some, The Griswold Inn is a home, a family, a community. For others, it may only be a stop on their travels. For a few it is a work of collective art, illustrating the perfect harmony of experiences collected through the endless movement of time. But on that misty day in February, I first saw it in a brand new way, as both the vessel and the painting.

Eric Lehman is the award-winning author of 22 books, including New England Nature, New England at 400, Quotable New Englander, and A History of Connecticut Food.