This article appears in the Summer 2024 issue

This article appears in the Summer 2024 issue

Chapter 14: Why Are We at War?

My little cousin, Ben, broadcast the news as he left my side and ran into his house, “JJ’s home! JJ’s home!”

Adam, his twin brother right behind him and letting the screen door slam for the second time, shouted, “He’s got a giant bandage on his hand!”

Hours later, word around Saybrook was that I had been wounded in battle, and, by the end of that day, I heard tell that I would receive a medal for my bravery. None of it true, excepting the bandage.

Truth is, my three-months of service as a Connecticut Volunteer were up. I had to turn in my Springfield 58-caliber rifle, and along with several in my unit I was sent back to Washington, DC, to get the bandage changed on my hand, shave off my beard, clean up, muster out, and be sent home. But, not everyone in my unit was headed for home. Those who didn’t muster out after three-months, signed up for three years like President Lincoln called on us to do.

![]()

I came back to Saybrook to think over what I’m going to do next.

![]()

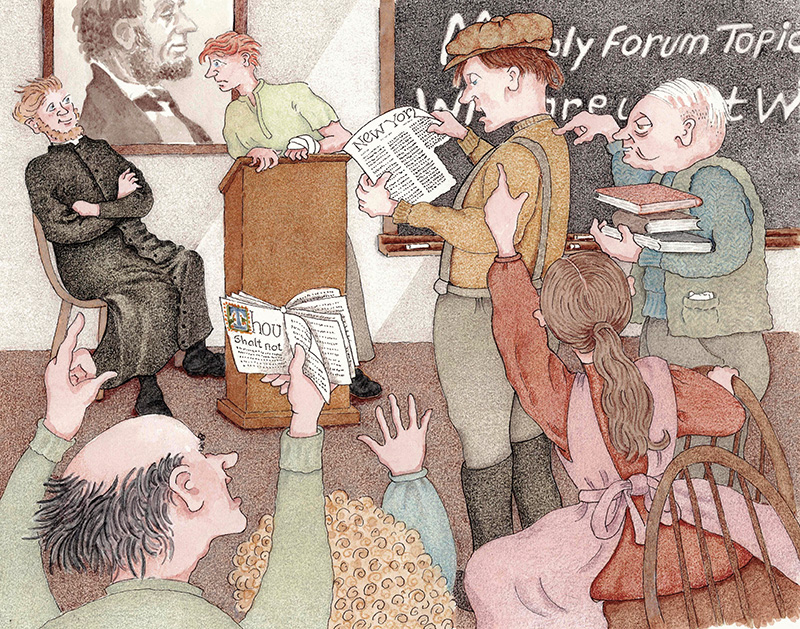

I had only been home two days when Reverend John at the Academy asked me if, as part of his regular monthly Forum, I’d be up for hosting the meeting and telling the people of Saybrook about my Army experiences. He already had a handbill: Why Are We at War? I read it and prayed to God he didn’t expect me to answer that question.

I bought my way into the Academy last year by handing over my hard-earned $100 so I could study oceanography and learn all I can about the Connecticut River, not to try and explain why the North and the South are at war. The Reverend promised me the purpose of me participating was for the people of Saybrook to hear about my experiences and try to fit “what you experienced into the wider scope of the war,” he said. “People love this forum and often come prepared with materials to share.”

![]()

Standing behind the podium made me nervous, but I knew just about everyone in the room, and most of them call me by name. Reverend John put me at ease when he spoke in a casual way and asked me if I would share some of my experiences, and then told the room full of citizens of Saybrook that they should wait to ask their questions or make a comment until I had finished my remarks.

I cleared my throat and started out, “Hello, everybody. The Reverend asked me to tell you what I did while I was serving with my unit of the Connecticut three-month volunteers in Virginia. I could tell you about how I got to see the US Capitol building when our transport ferry sailed by it at dawn, or how many bowls of beans I ate since I left Saybrook.” Everyone laughed, which made it easier to carry on. “But I know the Reverend wants me to stick to things related to the war.

“Our unit leader was Lieutenant Dunbar, a nice fellow and easy to get along with. Our mission was to clear a way across the Rappahannock River at Kelly’s Ford so the Cavalry could cross and not get blown out of the water by three cannons aimed directly at them. Our mission was to disarm those three cannons.”

People crossed their legs, sat up straight, and otherwise looked interested in what I might have to say next.

“On our march to Kelly’s Ford we came across some mapmakers doing reconnaissance for the Union Army. Their hot-air balloon was all tangled high up in some branches, so I volunteered to climb the tree and saw off the limb that would set the balloon free. I also helped build a pontoon bridge, which got us across the river so we could spike those cannons.”

Total silence. Some leaned forward, elbows on their knees, just waiting.

“We and the rest of our unit fired over their heads, waking the Rebels and chasing them into the woods, which bought us just enough time to spike the cannons. The Lieutenant carried the only hammer, so he spiked two of the three cannons. I picked up a rock to drive my spike into the touchhole of the third cannon. I hit the spike so hard that the rock split and sliced the palm of my hand wide open on the sharp edges, and that’s why I trimmed my shirt so I could fit this here big bandage through my sleeve. Well, that’s about all I’ve got to say about what I did,” I said, and I stepped back.

They all clapped for me, and shouted things like, “You made Saybrook proud, JJ!”; “A hot-air balloon, imagine!”; and “Good idea—pontoon bridge!”

Still clapping, Reverend John stepped up to the podium and said, “Thank you, JJ, for sharing your experiences with us. You can now open the forum up to the room to voice any questions or share thoughts or comments.”

“Why did you sign up, JJ?” A man asked.

Reverend John turned to me and waited for my answer.

“Good question!” another man shouted out, leaning forward, resting his arms on the chair in front of him.

“To be honest?” I said, “—because I was promised a Springfield 58-caliber rifle. I didn’t think about whether I got to keep it or not. That gun is such a beauty, and long, almost as tall as me if you put the butt-end down. Yeah, it was that gun.”

A woman near the back row stood up and said, “Well, young man, that’s just simply an idiotic reason to take yourself off to war.”

“No personal attacks on JJ,” the Reverend said. “Let’s keep it civil.”

The Reverend, trying to help out, said, “Can you tell us, JJ, other than that rifle, just what did you think you were fighting for? And, why you think anyone here should think it would be worth risking his life to sign up with the Union Army.”

From this point forward, the forum turned into a flood of opinions.

“Every southern state wants the choice to hold slaves or they say they’ll secede from the Union.”

“The Union Army is fighting to free the slaves, that’s obvious,” one white-haired man said with all the wisdom of his multiple decades.

“Oh, yeah?” said the man sitting next to him. “We’ve got plenty of slaveholders right here in Connecticut. Do we need to turn our Union Army on our own citizens?”

A tall man rose to his feet. A successful shad fishermen known by all, he took an article from his shirt pocket he said he had clipped from the New York Tribune and read Lincoln’s response to a column by Horace Greely, a known critic of Lincoln’s approach to the war. He unfolded it and read directly, quoting Abraham Lincoln: “If there be those who would not save the union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union and is not to either save or destroy slavery.”

“President Lincoln has since refined his thoughts about slavery!” a young girl said at the top of her voice, one arm raised. She wagged her finger at the shad fisherman, “We just learned all about it in school. Our President wrote up an Emancipation Proclamation to be officially put into law one year from now. That shows what’s in his heart and exactly where he stands. He is four-square against slavery.”

“Who are you, little sister, to speak for what’s in a man’s heart? He may be President, but he’s still a politician!”

Everyone was shouting, and hard as he tried, Reverend John could not restore order for several minutes. At one point he turned to me, smiled, and said, “It’s wonderful, JJ, isn’t it? This debate has been festering under the surface. Just look at what you started. You should be proud.”

“Proud?” The only thing the good citizens of Saybrook weren’t doing was breaking up the furniture or throwing haymakers, probably because there were ladies present, including my mother, whose eyes I searched to read what she thought about the fact that I created chaos. I got my answer when she smiled and winked at me, and my dad smiled and tapped the brim of his cap with two fingers.

![]()

Ray caught up to me the next day on my way to pay Squire a visit.

“Hey, wait up, JJ. That was some talk you gave last night at the Academy. Really got folks thinking.”

“Yeah! Got me thinking, Ray. I joined in a war I knew nothing about. I never gave a thought to the Union or why some states seceded. Spit! I am an idiot.”

“I’ve been wondering, JJ…” Ray took a long pause as we kept walking, “You suppose that, well, if we were to both sign up for the Union Army at the same time, we could serve those three years together?”

“What? … What did you just say?”

“I know, I know,” he said. “I was against you signing up, thought you put way too much stock in that fancy rifle, and not enough in the possibility that you could be shot by a soldier on the Rebel side with his own fancy gun. But, things are different now.”

“Different?” I said, as I knocked on Squire’s door. “What’s different?”

The door opened wide before Ray could answer and there stood Squire’s niece, Ashley wearing a Union Army nurses uniform with a red cross on the front of her apron.

“Hello, fellows.”

“I meant to tell you,” Ray said, “Ashley is serving in a field hospital in Virginia.”

“Just home for a bit to look in on uncle,” she said. “Then back to my post.”

Leslie Tryon is an award-winning author-illustrator of children’s books (Simon & Schuster publisher). Five generations of Tryon’s family served as ferrymen on the Connecticut River between Old Saybrook and Old Lyme, Connecticut, and many of those men were named JJ.

Historical Note

“Historians have long concluded that Southern states’ desire to preserve and expand the institution of slavery was the driving force behind a war that led to the deaths of at least 620,000 Americans. It was emphasized in numerous speeches by leaders on both sides at the time.

“Historians note that multiple attempts at compromise were made in the run-up to the Civil War and that negotiations came to an impasse over irreconcilable differences over slavery.”

Washington Post, 1/13/2024

by Toluse Olorunnipa