A woman dressed as 19th century doyen Phoebe Griffin Noyes wandered across the green grass of the Old Lyme Public Library lawn as my wife, Amy, and I shook hands with Wick Griswold. “Roooarrr!” he exclaimed, his standard greeting, with sunburnt, white-bearded face open wide. It was the Midsummer Festival, and we were all there to sell books as we did every year, making small talk with weekenders and locals, buying jewelry from silversmith Michaelle Pearson, and listening to Jim Lampos sing moody folk songs by the historical society’s white clapboard façade. A breeze off Long Island Sound rustled the trees and lamppost flags along Main Street from the Florence Griswold Museum to the town green, where patriots had burned heaps of tea in 1773.

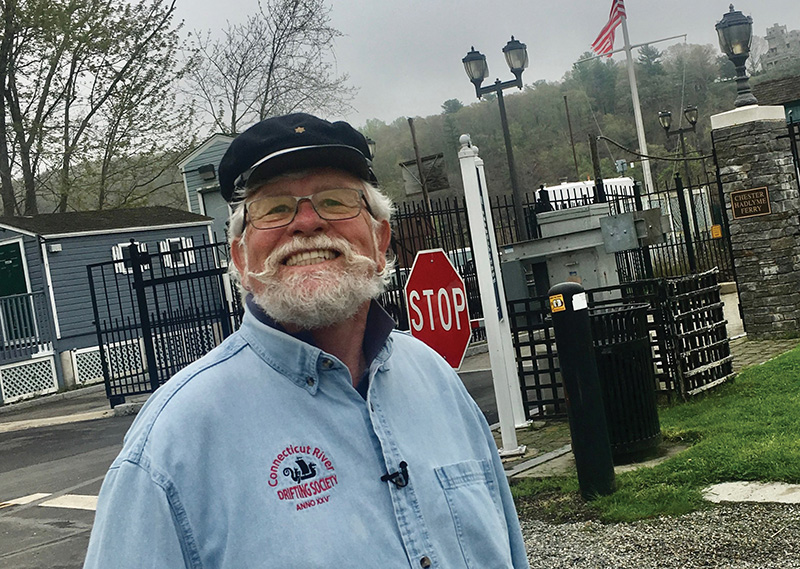

Wick Griswold (1944–2023). Image Credit: Stephen Jones.

Wick, Amy, and I sat on folding chairs under a tent and chatted with festivalgoers, who as usual rarely bought our history books. We ate kielbasa at the firehouse, drank lemonade, and tried to stay cool in the July heat. When the festivities slackened, we drove through salt marsh flats and cattail ponds to a local pub, where Wick’s wife, Annie, joined us as we cracked clean lobsters and sipped dirty martinis to celebrate not the few books sold but rather the fellowship created. Wick told stories of his crazy Griswold clan, and we planned to go “drifting” in his canoe soon. Although he was almost thirty years older, his heart remained so young, so fresh and light, with such humor and joy in the world, that I often felt like an elder brother.

Long before I met him, he had labored as a dock worker, truck driver, short-order cook, and commercial fisherman. But in those years, he worked as a professor of sociology known mostly as “Gris” at the University of Hartford, where he and his unorthodox teaching methods were legendary. The course he created, “Sociological Perspectives on the Connecticut River,” involved—among other activities—taking the students on annual expeditions to clean up the Connecticut River. He often taught these unique classes in his casual beach-life clothing from the bow of a canoe or by the flickering light of a campfire. “They paddled out to Great Island at the mouth of the river and dragged back a barge filled with flotsam,” Woody Doane, Wick’s long-time friend and Sociology department chair, told me. “I accompanied the class on several of these outings and know that many of his students found the course to be a transformative experience.”

“He fostered a respect for nature in a very immediate way by requiring students do some kind of community service,” agreed another friend, Roger Desmond, Professor Emeritus at Hartford’s School of Communication. “The Hog River runs directly through the campus; it’s now better known as the Park River and is part of the watershed to the Connecticut. Students from suburban, often affluent backgrounds, joined him in a major project which involved cleaning the Hog by hand, getting wet and seeing how trash thrown into the Connecticut could pollute it.” In addition to these expeditions, he led service-learning trips to Texas, New Orleans, and Puerto Rico after the areas had been damaged by hurricanes. On his retirement, the University of Hartford honored him by creating the Hillyer College Wick Griswold Award for Service.

His work in the community is equally legendary. In recent years, he hosted “Connecticut River Drift” on I-CRV in Ivoryton. His literary efforts included A History of the Connecticut River, Connecticut Pirates and Privateers, A History of Griswold Point, Connecticut River Shipbuilding, and Connecticut River Ferries. Two of these books were collaborations with Stephen Jones, professor emeritus in the Maritime Studies program at the University of Connecticut, Avery Point, and co-operator of two Mystic River maritime facilities.

Wick Griswold and Eric Lehman. Image Credit: Amy Nawrocki.

“While Wick certainly had the background to deal with the river in the most sophisticated of contexts, it was his wide-eyed enthusiasm for the water in its most primitive impact that not only first attracted me to him, but sustained our relationship,” said Jones. “Working with Wick was not much different than playing with him. There would be a swirling of data, images, words that seemed to be looking for some sort of a rhythm, a pattern, a home, and next thing you knew there were sentences, paragraphs, chapters, and next thing you knew: a book or a film or both!”

One of those films is the forthcoming The Connecticut: Our River, produced and directed by Vincent Hogan. He and Wick spent over six hours talking about the river. “We could have spent six days!” said Hogan. “He was a true steward of the river, and was dedicated to protecting and preserving it for future generations. He is one of the most inspiring people I know, and I am grateful for his friendship and mentorship.”

Wick’s stewardship of the Connecticut River inspired many, and helped make lasting changes in the way people interacted with it. What he really loved to do, though, was to drift on it. It was a term he picked up from Jones’s classic book Drifting, long before they became friends and collaborators. He led the Connecticut River Drifting Society as its “Commodore,” telling his accomplices, “See you on the ‘rivah,’” or “T’aint a river until you fall into it.”

“For Wick, rivers were sites that connected the past and the present, the local with places far away (upstream, downstream, or across the ocean), and people with nature,” said Doane. “Many of my most treasured memories are of time we spent along the Connecticut River—camping on Selden Island, paddling along the river and one of its estuaries like Whalebone Creek or Black Hall River, and riding across the river from Hadlyme to Chester on the Selden III. His love for the River affected (and infected) all of his friends.” Roger, Woody, Vincent, and everyone I talked to are proud to be among his converts. So am I.

One beautiful summer day, Amy and I visited Wick and Annie at their cottage on Griswold Point. Wick had spent his summers on the Point since he was a child, but he and Annie had just moved permanently into one of the smaller houses on the land that his extended family had lived on for almost 400 years. Before a dinner of scallop pie, they took us on a stroll past the white clapboard perfection of the Big House and into the salt-crusted trees. We walked soft sandy lanes, speaking of our mutual love of shad, that “inside-out porcupine”-of-a-fish with its tender white flesh. He pointed out naturalist Roger Tory Peterson’s house on the far side of the Black Hall River, the ospreys hovering over Great Island, and the piping plover and least tern nesting areas on the sand bar. We talked about the history of his family, the governors and ship captains, the Congressmen and innkeepers. But it wasn’t faraway events he described, it was as if all this was still happening, as if we lived in it, right now.

“Lady Fenwick is my favorite,” he said. “Expert with a gun or with a song.”

“What’s it like to have that sort of family history?” I asked. “I mean, to live in the same place, to have such illustrious relatives…?”

“It’s a gift to have that continuity,” he mused. “And a burden.”

Nowhere did I feel closer to history than the day we walked amongst the driftwood and purple flowers on Griswold Point. But what Wick really taught me had little to do with the past. He taught me that we are always in the now, the place where we can make a difference, where we can transform a mind or heart. On the lucky days I spent with Wick, I tried to pay attention to the way he lived—in the moment, with a profound joy, eating up life as if it were a fine lobster, a twinkle in his eye and a smile splitting his old seadog face.

“Onward and awkward!” he cried, and we followed.