Hidden Gems of the

Wild and Scenic Westfield River

Story and photos by John Burk

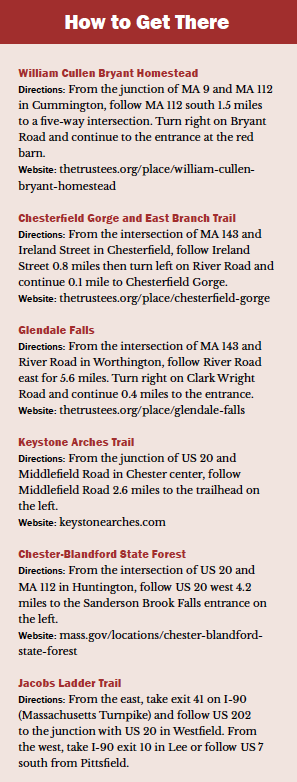

Set on a historic railroad line in the scenic Berkshire foothill towns of Middlefield and Chester, Massachusetts, the Keystone Arches Trail offers a fine sampling of the Westfield River watershed’s rich natural resources and history. As I walk along an abandoned railroad bed and old turnpike on the banks of the river’s West Branch, views unfold of cascading streams, rolling valley hills, unbroken forests, and the trail’s namesake, a series of striking nineteenth-century stone arch bridges built as part of the Western Railroad, America’s first mountain railway.

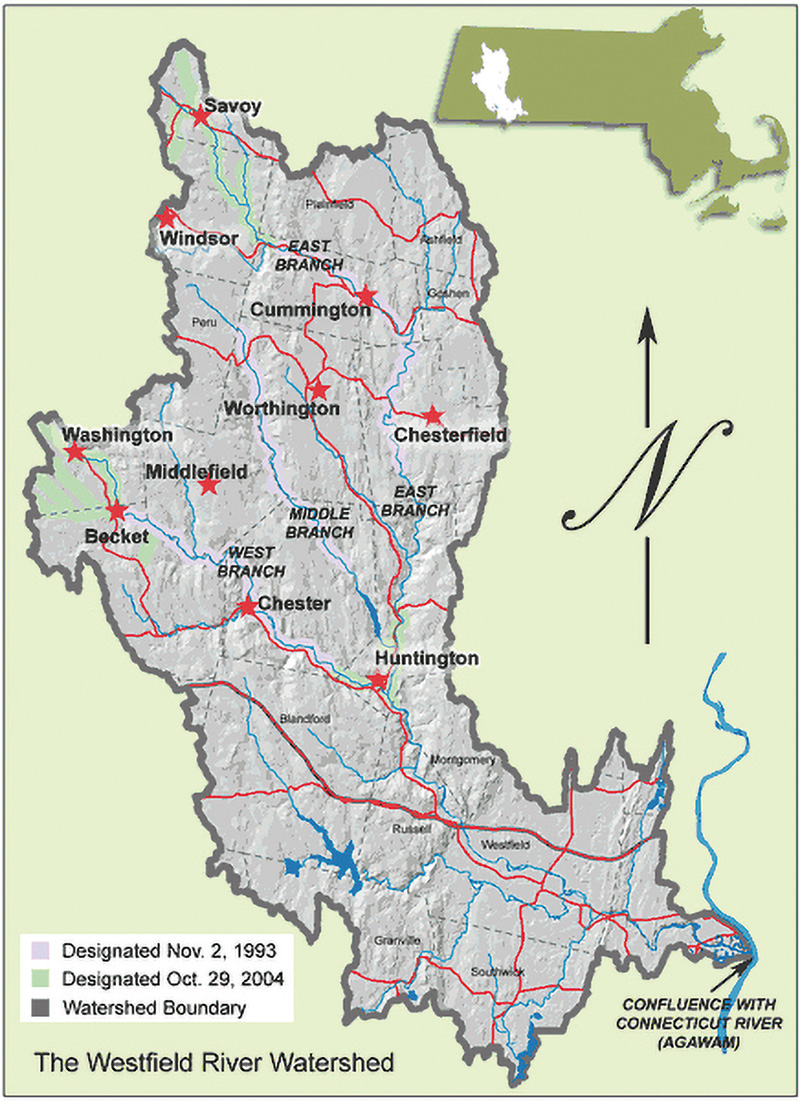

The Westfield River, the Connecticut River watershed’s first National and Scenic River and longest tributary in Massachusetts, drains a largely undeveloped, densely wooded 520-square-mile basin that stretches from the eastern Berkshire Hills to the lower Pioneer Valley. Three major tributaries, the East, Middle, and West Branches, converge in the town of Huntington to form the main stem, which joins the Connecticut River near Springfield. Designated Wild and Scenic segments, established in 1993 and 2004, include 28 miles of the East Branch, 16 miles of the West Branch, 13 miles of the Middle Branch, and 20 miles of headwater tributary streams and brooks. These waterways support diverse fish communities, including trout and other cold-water species, one of the Connecticut River watershed’s largest shad runs, and Massachusetts’s only lake chub population.

Westfield River with autumn fog rays.

In the words of ecologist Glenn Motzkin, whose work includes surveys of rare plants and invasive species in the watershed, “The Westfield River is widely recognized as one of the highest priorities for biodiversity conservation in southern New England and represents one of the region’s few river basins with relatively intact hydrological and ecologic processes. High concentrations of rare species, exemplary natural communities such as riverside meadows and floodplain forests, and extensive areas of high-quality wildlife habitat and cold-water fisheries highlight its significance.”

From a viewpoint atop an abandoned bridge on Keystone Arches Trail, I pause to take in views of the West Branch, Massachusetts’s longest free-flowing river reach, as it winds past steep hills downstream from headwaters in October Mountain State Forest. Despite rugged terrain, the valley provided the most feasible route across the eastern Berkshire Hills for Western Railroad designer George Washington Whistler. Completed in 1841, the railway, which established a crucial link between Boston and Albany, included ten river crossings on intricately crafted stone arch bridges. Two arch bridges remain in service on an active line, and two abandoned structures were designated as National Historic Landmarks in 2021. A former depot in the nearby center of Chester now houses Chester Railway Station Museum, open seasonally on weekends.

Downstream from the Keystone Arches, Chester-Blandford State Forest encompasses 2,300 acres of wooded hills, cascading brooks, and old mine and quarry sites on the south side of the valley. A mile upstream from its confluence with the West Branch, Sanderson Brook drops 60 feet over steep ledges at popular Sanderson Brook Falls. Less-traveled Goldmine Brook Falls lies within a hidden ravine off Route 20 near the Boulder Park entrance. A lookout atop aptly named Observation Hill, reached via a rugged half-mile ascent from Sanderson Brook Road, offers a fine perspective of the West Branch corridor. Nutrient-rich soils sustain abundant spring wildflowers such as red trilliums, Dutchman’s breeches, and trout lilies.

Image Credit: Wild & Scenic Westfield River Committee.

A few miles to the northeast, the Middle Branch winds through a narrow valley in the lightly populated hills of Worthington, Middlefield, and Chester. Several state wildlife management areas protect nearly 10,000 acres of headwater wetlands and adjacent northern hardwood forests, providing habitats for a variety of wildlife including moose, black bears, bobcats, beavers, waterfowl, and wading birds. On a steep rocky hillside in Middlefield, Glendale Brook drops 160 feet over ledges and boulders at Glendale Falls, one of Massachusetts’s largest waterfalls.

Deep valleys and thin soils made the Westfield River watershed historically prone to damage from storms such as the November 1927 flood, which washed away mill dams in Becket and destroyed three of the Keystone Arch bridges. Littleville Dam and Knightville Dam, built in the mid-twentieth century near the confluence of the Middle and East branches, provide flood protection for Huntington, Westfield, Springfield, Hartford, and other communities. In addition to flood storage, Littleville Lake, one of 78 lakes and ponds in the Westfield River basin, provides boating and fishing opportunities and serves as a backup water supply for Springfield. Releases from both impoundments provide consistent flows for the Westfield River Whitewater Race, the nation’s oldest annual canoe race.

The East Branch, largest of the tributaries, emanates from headwaters on the slopes of the Hoosac Mountains in the northern Berkshires. Windsor Jambs Brook, one of its sources, cascades 100 feet through a narrow granite gorge lined with 80-foot cliffs in the heart of Windsor State Forest. Surrounding high-elevation spruce-fir woodlands impart a winter wonderland feel for cross-country skiers and snowshoers.

Atop the south side of the valley in Cummington rests the pastoral former homestead of acclaimed nineteenth-century poet and New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant. Now owned by the Trustees of Reservations, a private conservation organization whose landholdings also include Chesterfield Gorge and Glendale Falls, the property’s attractions include Bryant’s boyhood home and late-life summer retreat, a photogenic red barn and hayfield, and the Rivulet, an enchanting old forest with 150-foot-high white pines and 200- to 300-year-old hemlocks, birches, and maples.

At the nearby confluence with the Swift River (not to be confused with the Swift River in central Massachusetts that supplies Quabbin Reservoir), the East Branch bends south through the “Pork Barrel,” a seven-mile reach in Chesterfield with deep pools and a long gorge bordered by woodlands of Gilbert Bliss State Forest. Paddlers prize this section for strong continuous rapids and outstanding scenery.

Chesterfield Gorge, one of the watershed’s best-known landmarks, stands as another testament to the carving power of high-energy waterways. Scoured by glacial meltwater and the East Branch over thousands of years, its granite walls rise as high as 70 feet above the river. Stone abutments at its upper end mark the former site of the High Bridge, built in 1762 as part of the Boston Post Road, a colonial thoroughfare between Boston and upstate New York. Downstream from the gorge, East Branch Trail continues through a protected corridor along the riverbank past cascading streams, old mill and bridge sites, a broad hollow once farmed by Native Americans and colonial settlers, and a state wildlife preserve within Knightville Dam’s flood-storage area.

From the confluence of the three branches in Huntington, the Westfield River main stem meanders 26 miles along the transition from Berkshire uplands to the Connecticut Valley. Steep exposed cliffs of Tekoa Mountain, one of the watershed’s most distinctive natural landmarks, loom over the north side of the valley in Russell and Montgomery. Its barren slopes and regionally uncommon pitch-pine-scrub oak forests are evidence of natural fires. Informal trails lead to views of the Westfield and Connecticut river valleys, a Massachusetts Turnpike highway bridge, and the cities of Westfield and Springfield. Old mills and factory villages in Russell, including the former Strathmore Paper Company site, stand as artifacts of the river’s industrial heritage.

Along the main stem and lower West Branch runs Jacob’s Ladder Trail Scenic Byway, a picturesque 35-mile stretch of Route 20 extending from Russell to Lee. Built in 1910 as the nation’s first mountain-crossing auto road (predating the Mohawk Trail Highway by four years), it ranked as one of the region’s most-traveled highways during the early twentieth century and was part of the Yellowstone Trail, a transcontinental route from Massachusetts to Washington State. Travelers enjoyed multistate views from the Summit House at the road’s height-of-land in Becket. Today the Trail retains much of its historic character as it traverses largely undeveloped valley towns and villages.

Upstream from its confluence with the Connecticut River, the main stem passes through the lower Pioneer Valley, where eighty percent of the watershed’s population resides. Prior to European settlement, the Woronoco, part of the overall Pocumtuck nation, established a village in the fertile floodplain. Westfield, settled around 1660, became an agricultural and manufacturing center with a variety of industries, including paper and powder mills and whip makers. The Metacomet Range traprock ridges of Provin Mountain and East Mountain, part of the 215-mile New England National Scenic Trail, serve as a crucial protected corridor amid development. Adjacent Robinson State Park features an extensive trail network on the river’s south banks.

Efforts of Westfield River Watershed Association (WRWA), Wild and Scenic Westfield River Advisory Committee, and partner organizations are crucial in preserving the river and its many attractions. Founded in 1953, WRWA has coordinated many land conservation, ecological restoration, water quality, and education and outreach initiatives over the past seventy years. The river’s relatively clean water stands as a marked contrast to the mid-twentieth century, when it suffered heavily from industrial pollution. WRWA President Brian Conz cites current priorities as “addressing effects of climate change on the watershed and recreation, supporting river access for underrepresented and marginalized groups, developing a more diverse board, and infusing our activities with an ethic of environmental justice.”

At Keystone Arches Trail’s western end, I reach the remains of an arch bridge that washed out during the 1927 flood. Calls of migratory songbirds echo from the valley’s densely wooded hills, and a mink makes hunting rounds on the rocky riverbank. Heading back to the trailhead, I pass numerous hikers, fishermen, and paddlers, all enjoying the watershed’s many amenities. Several freight and passenger trains rumble along the active rail line across the valley, underscoring the Western Railroad’s legacy.

John Burk is a writer, photographer, and historian from western Massachusetts whose credits include 15 books and guides and articles in nature and regional publications.