Chapter 11: Out on a Limb

My battalion of three-month Connecticut Union Army volunteers, along with a cavalry unit and a couple of drummer boys, sailed out of New Haven on board a double paddle-wheel ferry headed for Camp Glenwood, a mile or two north of Washington, DC. The Captain told us it would take us three days to get there.

Three days sailing on a big paddle-wheeler might be pretty exciting for a fifteen-year-old like me whose longest sails were the half-mile or so between Saybrook and Old Lyme on our little family ferry. But, now that those three days are behind me, I’ve got more bad than good memories. And I’m not alone.

We soldiers complained because the Cavalry horses and mules were tethered to rope lines that stretched the whole way across the upper deck, leaving no space for a fellow to come up out of the hold and get a breath of fresh air. The Quartermaster complained of not having enough hay and grain to feed the animals. I’m no expert on horses, but some of them looked like no amount of food was going to make them battle ready. Not a one of us could draw a deep breath for the general stench of manure and the horse and donkey pee that leaked through the upper deck and down into the first deck below where we soldiers spent those three days.

We were awakened predawn our third day sailing to the steady roll of a snare drum reveille, and Lieutenant Dunbar’s voice. “Wake up call!” he shouted. “We passed through the Chesapeake Bay while you slept and are now sailing up the Potomac River toward Camp Glenwood. If you’re interested, we’ve reached a spot in the Georgetown Channel where a soldier can get a great view of the US Capitol building off our starboard side. That is, a soldier could see the Capitol if he were up top instead lazing away on his cot.”

“Permission to go topside, sir,” several men said at once.

“Permission granted,” the Lieutenant said.

Since we slept in our clothes, all we had to do was jump into our boots and lace them up. We bolted past the wash basins, ignoring the standing order to wash our face and hands first thing every day, nearly knocking the Lieutenant and the little drummer boys down as we scrambled up the ladder and out onto the top deck.

“Single file! Single file!” the Lieutenant shouted as we passed.

We all balled up in one spot topside because there wasn’t space along the railing for so many of us to spread out single-file and catch sight of the Capitol.

I took advantage of the confusion and made my own opportunity. I slipped under the ropes and climbed onto the back of one of those horses.

“Get down from that horse, soldier! Now!” the Quartermaster shouted.

But it was too late. Lots of other fellows, seeing what I had done, did the same.

It was worth getting yelled at. What a view of the Capitol I got, with the sun just rising in the east behind it. I never would have guessed seeing a building could give me goosebumps or make me feel so proud.

“Fresh baked bread!” Stephen shouted, sitting low in the swayed back of a mule.

“You’re just conjuring,” I said. “You’re so desperate for fresh air.”

Pretty soon lots of fellows are shouting, “Hey! Smell that? Somebody’s baking bread!”

We were exhausted after three tough days on the ferry and a full day of drill, but we didn’t get to sleep that night in Camp Glenwood like we thought we would. As soon as we finished a hearty supper of bean soup served up with plenty of homemade bread, I put on my haversack, took up my rifle, and joined my battalion a for a night march. Lieutenant Dunbar, and the two drummer boys with their steady cadence, led us through the warm and humid night to take advantage of the high visibility provided by the full moon.

Night critters, like raccoons, opossums, foxes, and skunks would appear in our path from time to time, and disappear like ghosts, into a bramble or thicket when they saw us. At one point, I had stopped just long enough to take a drink of water from my canteen when an owl dove down a few yards in front of me, grabbed a scrambling vole, and flew back up into the trees, all without making a single sound. Rest in peace, little vole, I said to myself. Marching through the quiet moonlit Virginia woods reminded me of how much I like sitting in my uncle’s currach back home, fishing for shad by lantern light on my Connecticut River.

The bright moonlit night gave way to a cloudy, gray, and windy first light. Exhausted and nearly asleep on our aching feet, Lieutenant Dunbar had just ordered us to set up camp at the edge of a small wood when we heard the sound of voices and gunshots. We dropped our gear, set our bayonets, armed our rifles, took shelter among the trees, and listened.

Who was firing the rifles, Union or Confederate? Who were they firing at? A sickening cold swept over my stomach and my thighs. Fear.

The Lieutenant pointed to me and three other soldiers and signaled for us to move forward with him. We followed the sound of footsteps, dodging around bramble and trees. Within minutes we had surrounded the shooters who turned out to be three barefoot kids with 22-caliber rifles.

The Lieutenant pointed to me and three other soldiers and signaled for us to move forward with him. We followed the sound of footsteps, dodging around bramble and trees. Within minutes we had surrounded the shooters who turned out to be three barefoot kids with 22-caliber rifles.

“We scouting for President Jackson!” they shouted. “We just scouts! Don’t kill us!” The Lieutenant fired over their heads, and they retreated to the west.

“Spit! They’re just kids,” I laughed.

“If a kid’s a good shot, and he’s aiming at you, you’d be just as dead,” the Lieutenant said. “Remember that.”

“Am I supposed to fire back at a kid?” I asked, but he didn’t hear me.

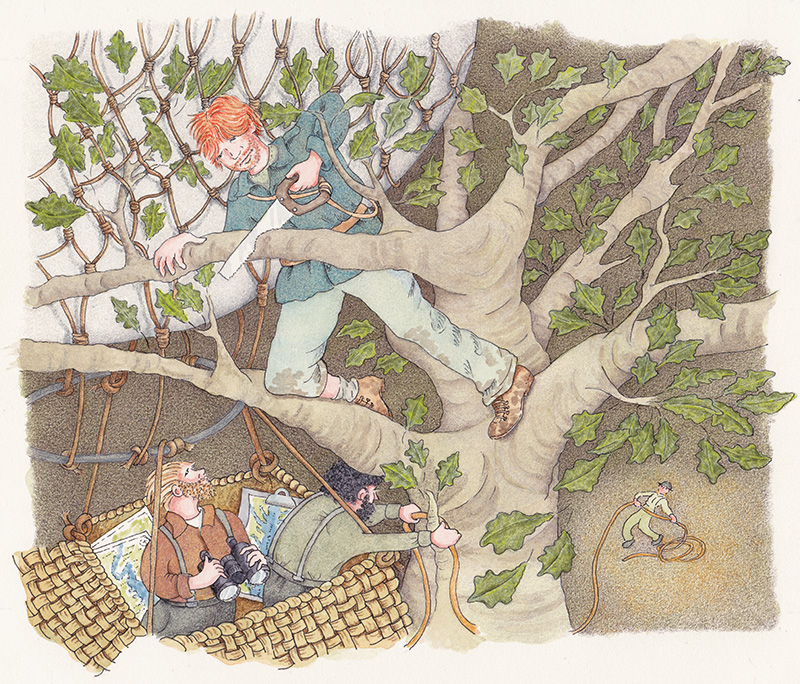

After several minutes of leading us in a zigzag pattern through the woods, the Lieutenant stopped abruptly, signaling silently for us to halt. We clustered together alongside an ancient oak at the edge of a large clearing and tried to make sense of what we were looking at.

We saw five unarmed men out in the open. Each man grasped a heavy rope with both hands that led up to a basket big enough to hold the two grown men inside. The basket was cockeyed, all tangled up in some branches maybe thirty feet up off the ground.

It was a hot air balloon, just like one I saw in a drawing once, only this one didn’t have tassels and buntings hanging off of it and wasn’t painted all over with bright colored pictures. This balloon was just plain fabric, like the sailcloth we used for grandfather’s old sail ferry, only not as heavy, and it was draped with something like fish netting.

We followed the Lieutenant’s hand signal to move forward, walking out from the safety of the trees and into the open, our rifles trained on the men.

“Don’t shoot!” they shouted.

“You Union?” The Lieutenant asked.

“Civilian,” one man said. “Doing reconnaissance for President Lincoln. For the Union.”

“What’s, ‘rec’… that?” I asked.

“Reconnaissance,” Lieutenant Dunbar answered.

“Some call it, spying,” one of the men said. “If we can raise this balloon a thousand feet, the men in the basket will be able to see fifty miles in every direction. We pull it back down again when they signal that they’ve finished their mapping. A big gust of wind caught hold of the balloon this morning, and next thing we know it’s caught in the branches of that tree. Then we heard gun shots.”

“If it was the shooters we chased down,” the Lieutenant explained, “they’re just kids. Claimed they were scouts. You make maps for the Union Army? Think you can you see as far as Kelly’s Ford from up there? That’s where we’re headed; it’s on the Rappahannock. It sure would help to know if there’s a Confederate position near there.”

“Kelly’s Ford?” one man asked. “Got to get this balloon loose first before we can raise it and get a look around. First, we need a fellow tall enough to reach that bottom branch there, then climb up to the basket.”

“I can!” I said. “I’m tall enough.”

“If you can climb up that tree and free the basket, soldier, you can ride her back down with the crew.”

“Is there room for another person?”

“They’ll squeeze you in, soldier,” he said, and handed me a saw.

“I’m happy to help these fellows, Lieutenant. With your permission. Sir.”

“Carry on, soldier,” the Lieutenant said.

I grabbed that lower tree limb with both hands, walked my feet up the tree trunk to a limb a yard or so above my hands, slung both legs over that limb until I was hanging by my knees. I freed my hands, pulled my body up, and began to move up into the tree, climbing around the limbs and foliage, until I found the perfect spot to balance and begin working the saw.

Dear Mum and Cap,

The picture on the other side of this postcard is of the Bienville ferry, the one that carried us troops and cavalry horses down south to DC. I went up in a hot air balloon. I’ll tell you more about it when I have time to write a real letter.

I’m growing a beard. It’s coming in red, just like you guessed it would, Cap.

Your son—Jeremiah-JJ-Jedidiah

Historical Notes

“Workers constructed 20 ovens in the US Capitol basement to bake bread for the thousands of troops camping in and around the city.”

Architect of the Capitol, aoc.gov/explore

~~

Abraham Lincoln had a keen interest in an air-war mechanism to use for reconnaissance purposes. Aeronaut Thaddeus Lowe coordinated with Topographical Engineers to make preliminary observations for the purpose of mapping Confederate battlefields. The Balloon Corps served the Union Army from October 1861 until the summer of 1863.

National Park Service,

Air Balloons in the Civil War

~~

For this story, I’ve referenced a letter, written by my great uncle, about the three days he spent on a troop ship with the 7th US Cavalry, 400 horses, and 200 mules.

Sargent Edward Sullivan,

Battery. H. 2nd US Artillery 321’

~~

The daily ration for Union cavalry horses was 10 pounds of hay and 14 pounds of grain. A soldier’s daily ration weighed a little more than 4 pounds.

Three million horses and mules served during the Civil War; approximately half lost their lives. May 4, 1861—Abraham Lincoln’s compassion for animals led him to initiate the service of a veterinary surgeon to each cavalry unit to care for the animals so vital to the war. Two years later the American Veterinary Medical Association joined the effort.

~~

My thanks to the Old Saybrook Historical Society for their work in gathering material used in this series.