Many areas in this country have icon species that add richness to their sense of place. The Texas Gulf Coast is busy working to restore the iconic Kemp’s ridley sea turtle, and we have here in the Connecticut River watershed the American shad (Alosa sapidissima).

Dams built in Connecticut and Massachusetts in the 1700s extirpated our icon species, the American shad, from the upper valley. For all the disappointment over the failure of the salmon restoration program, shad have benefited by work done by the Connecticut River Atlantic Salmon Commission (CRASC) especially from the addition of fish passage facilities at the dams from Holyoke, Massachusetts, upriver to Wilder, Vermont, that have the American shad again returning to the Connecticut River in large numbers.

American shad are typically 20 to 24 inches in length and as anadromous fish spend most of their lives in saltwater. They range along the Atlantic seaboard and its large river estuaries from Labrador to Florida. As adults, they travel in large schools along coastal areas and may migrate more than 12,000 miles over 4 or 5 years until they are sexually mature when they return to freshwater rivers to spawn.

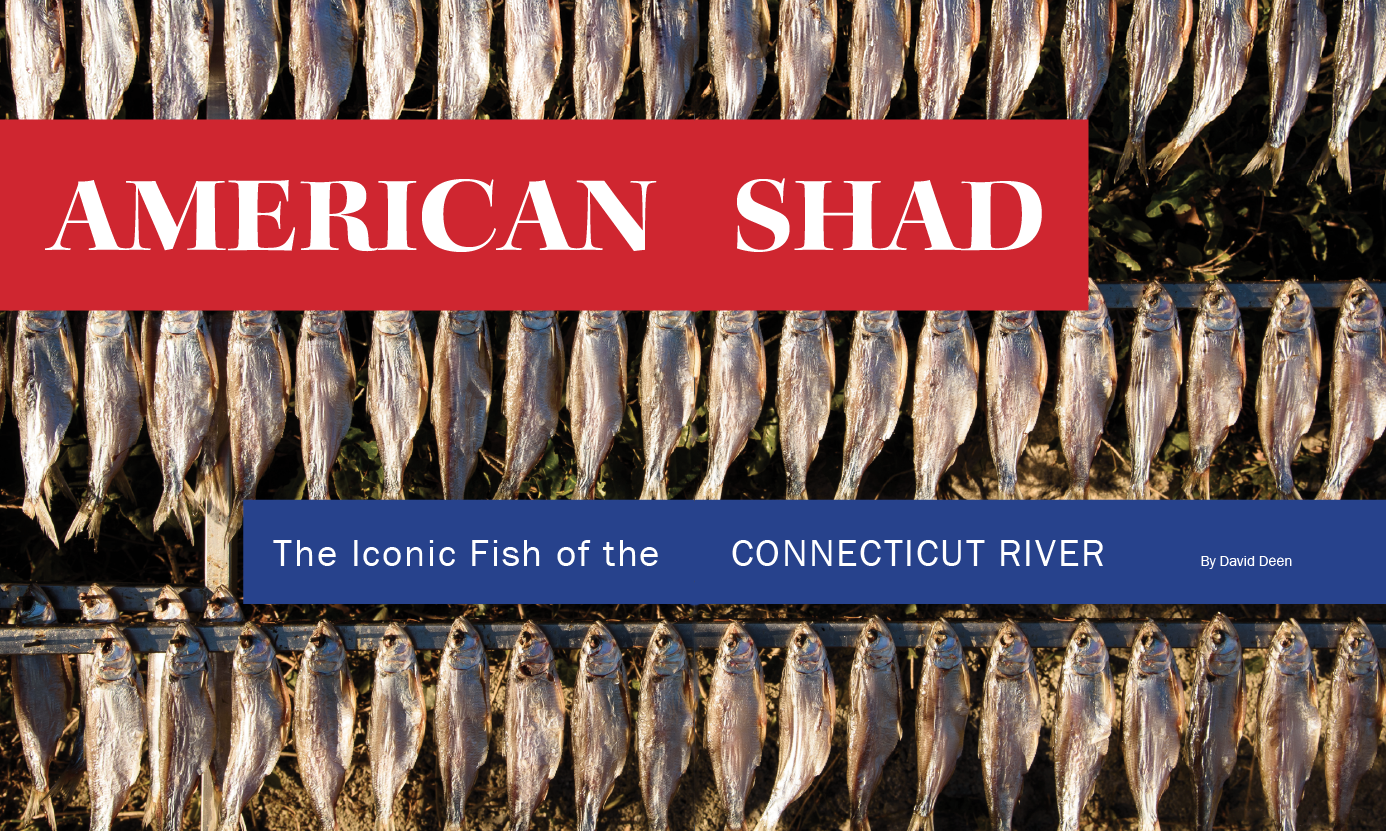

Historically, Native Americans harvested shad during the spring spawning run, teaching colonists how to catch shad to feed their families. History has credited dried shad with saving George Washington’s troops from starvation as they camped along the Schuylkill River at Valley Forge. By the early 1800s, anglers caught shad by the ton. Farmers took advantage of this seeming endless supply, using shad as fertilizer for their fields.

Native American petroglyphs at a shad harvest site in Bellows Falls. Image Credit: Al Braden

At best, only one percent of the fertilized eggs will become adult shad. Southern populations spawn, and then almost all die. Northern populations like ours have some survive spawning; meaning that up to 30–60% may live to return to the Connecticut River to spawn a second or third time. Fish that do survive can live for ten years.

Larval and juvenile American shad are prey for a variety of predators including American eels, black bass, and striped bass, supplementing the food chain that supports some of our favorite game fish. Once shad enter the ocean, they are food for sharks, blue fish, tuna, and porpoises. Adult shad in rivers have few predators other than human fishers.

Shad are primarily plankton feeders, but when offshore, they feed on small crustaceans, shrimp, fish eggs, and occasionally small fish. Larvae consume small crustaceans, midge larvae and pupae, and caddis fly larvae. Scientists found that in freshwater Chironomid, a small aquatic insect larvae and pupae made up over half the diet of shad.

Depending on the source, the shad name can mean delicious, savory, good to eat, or most delicious, but the meat of the fish is filled with bones. One Native American legend has it that the fish began as an unhappy porcupine and the Great Spirit grew tired of its complaining and turned it inside out; thus the bony shad.

But there are three ways to make the fish more palatable. One is to slow cook it by steaming, dissolving most of the smaller bones. The shad roe (egg sacks) are excellent fried or sautéed without any special treatment.

Shad planking, 1893. Image Credit: Library of Congress/William Cruikshank

The second is the traditional “planking,” comprised of boning the shad filet as best you can, nailing it to a plank with a thin strip of salt pork or a strip of bacon, and standing it upright next to an open fire. Again, the filleting and the slow cooking make the fish more enjoyable.

There are some, though, who offer a third choice, and they would change the plank slow cooking method just slightly. When asked, they would tell you to nail the filet to the plank with bacon or salt pork, slow cook it close to a fire, and then throw the fish away and eat the plank and the bacon.

There are few freshwater fish that will take a flyrodder into their backing. Most of our freshwater species live in smallish, discrete habitat areas, limited in scope like pools, and although some of our usual target species fight hard, they tend to jump, dive, or swim in circles the size of their habitat to escape. Not American shad—they come from the ocean, and with a life history that might include 12,000 miles of migration, a long hard run is firmly in their heads. So that’s what they do: they run, and it takes a strong leader and a resistant drag to hold one back from making it back out to the ocean.

There are several ways to fish for shad on the fly. You can launch a boat below Bellows Falls and at the other dams downriver from there. They each have a boat launch, but a word of caution: it better be a small boat or skiff, because the launches closest to the dams are little more than oversized car top launch sites.

Once you are on the water, you need an anchor so you can sit right in the flow coming through the dam, or you can float downstream while casting and retrieving a shad dart and then troll the dart coming back upriver. If shad are there, they are holding in the current about three feet below the surface.

For the most part, shad are moving upstream, and as noted earlier they are waiting for the right water temperature to trigger spawning. But at the face of a dam, until they discover the attraction flow at the fish ladder, they circle back downriver and then try swimming upstream again. Since they travel in small schools you can see them circling endlessly until they find the ladder.

There are some of us fishers who do not own boats for one reason or another or don’t like the idea of falling out of something when we can have our feet firmly on the ground, nothing to fall from. So, my preferred way to fish for shad is to wade fish for them. Unfortunately, the Connecticut River is big and deep and does not welcome wading fishers except for a few unusual situations. This article will talk about two of those locations.

Angling for American shad on the fly. Image Credit: David Deen.

And then there are the flies. Like all anadromous fish, shad do not feed when they return to fresh water. Their physiological changes force them to move upriver solely to spawn, but they do strike at certain brightly colored flies as a defense/offensive reaction. No one has quite figured out what they are doing, but strike they do, and they like gaudy, flashy, size 8 to 12 streamers, with bead eyes. Shad have tender mouths, especially the lower lip, so the flies are tied with the bead eyes tied on top of the hook so the hook turns over when stripped through the water. A successful hook set will be in the top of the fish’s mouth.

For whatever reason they strike, it takes a wee bit of strategy to get a fly in front of a shad. The fish tend to favor swift moving water. They usually swim one to three feet below the surface and in order to drift a shad dart right past their nose takes a full sinking or fast sink tip line with a weighted fly. The usual approach is to cast 45° down and across the current, mend your line immediately upstream then let the current pull the line downstream. While it is drifting twitch it, two twitches, pause, two twitches, pause, repeat. Once hanging straight downstream in the current strip it in, strip, strip, pause, strip, strip, pause, repeat. Muscle up your tippet to 3X on a 7-foot leader.

Rock Wall is the locals’s name for a site on the bypass reach of the river below the Turners Falls hydro dam. The bypass is the original riverbed, but because most of the flow through the dam flows down a canal terminating at the Turners Falls power station, the bypass reach has a lower flow, low enough to allow for walking the shore and/or wading to fish for shad on a fly. Rock Wall is a formation causing a small waterfall; downriver there is gravel bottom that welcomes wading.

Getting there is straightforward. The pullout parking area for Rock Wall is on Migratory Way, the street that leads to the Silvio O. Conte Anadromous Fish Research Laboratory in Turners Falls. The trail down to the river is obvious.

And then in the same reach of river there is Station 1 that is a small hydro power generation facility that gets the water to turn its turbine from the canal. Some small amount of water from the canal flows through the generators and into the bypass reach about a half mile above Rock Wall. The power station flow creates a situation much to the shad’s liking—fast moving water that tastes like upstream. How do you get there? Well, my advice would be to ask someone in Turners Falls the location of Station 1. Once you find it look for the fire hydrant and then go through the owner provided break in the chain link fence and keep going downhill to the river.

When the fish are in the river, angling for them is a real treat. In order to time your trip so that fish are present, search for the website for the Connecticut River Atlantic Salmon Commission and click “fishway counts,” or follow this link: www.fws.gov/project/connecticut-river-basin-fishway-passage-counts.

When you are angling for American shad the phrase “tight lines” has a fun new meaning.