Be A Citizen Scientist and Enjoy the Fun!

Bird counts record many species like this sanderling. Image credit: Ray Uzanas.

Have you tried becoming a citizen scientist yet?

I was one for a few hours in February during the Great Backyard Bird Count (GBBC), an exciting, global event, where everyone adds their sighted birds into a database—and loved it. It was fun, easy, and I came away feeling like I made an impact.

What is a citizen scientist?

According to the Oxford Dictionary, it’s when a member of the public “collects and analyzes data relating to the natural world, typically as part of a collaborative project with professional scientists.”

Examples of citizen science at work might be as simple and meaningful as sampling water quality in a local stream for the Nature Conservancy or helping wildlife biologists count salmon that are using fish ladders to get around hydro dams and leap upstream to spawn in rivers like the mighty Connecticut River.

The wonderful point about being a citizen scientist is it doesn’t matter how old you are or what your background is. Anyone can be a citizen scientist. “All it takes is some time, curiosity, and a sense of wonder,” notes the National Park Service, one of many federal agencies who employ citizen scientists like you and me to help them collect data and better understand the world around us.

Why did I choose to participate in the Great Backyard Bird Count? Because I love birding and it was convenient. All I had to do was pick a site: my own backyard, a street, a park, or take a stroll along the seashore. Then, for at least 15 minutes or more, during any one of the four assigned days (in this case, it was February 17–20), record the different species of birds that I saw—how many, their approximate location, the time of day—and then report them on a free website, called eBird.org.

Personal Benefits

If you have an interest in becoming a citizen scientist, my advice is to choose a project that matches your hobbies. Then, as you know, the activity becomes far more enriching.

In my case, I spent two hours in the sunshine, walking in a lovely land trust, bordering Long Island Sound, and recorded two hooded mergansers, four buffleheads, and six sanderlings, a total of three different species and twelve birds.

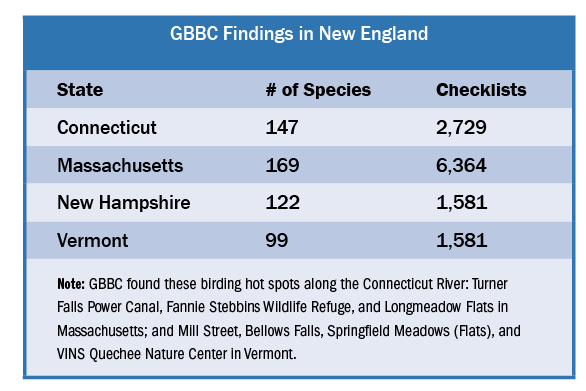

Was I proud to be part of a global effort? You bet! Here are some of the impressive worldwide results of the 2023 GBBC, provided by The Cornell Lab of Ornithology:

-7,538 different bird species were reported. (That’s two-thirds of the 10,960 known species that inhabit our planet.)

-202 countries participated in the four-day event.

-390,652 “checklists” or bird lists were submitted.

-151,479 photos, videos, and sounds were uploaded.

-555,291 estimated global participants observed birds—and I was one of them!

Another benefit of becoming a citizen scientist is you often get to rub shoulders with frontline scientists who are performing cutting edge experiments and learn from them.

Another benefit of becoming a citizen scientist is you often get to rub shoulders with frontline scientists who are performing cutting edge experiments and learn from them.

For instance, I learned that the GBBC is in its 25th year. Launched in 1998 by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society, the GBBC is now growing so quickly, it’s mushrooming! In 2021, for example, an estimated 300,000 people worldwide participated, compared with more than half a million this year.

“Historically, the GBBC event was national. Then we expanded to Canada, and now it’s global, with over 200 countries participating this year,” explained Becca Redomsky-Bish, project leader for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s GBBC.

Why are bird counts important?

“Large, global bird counts, like GBBC, allow us to monitor changes more closely in bird populations over time. They tell a compelling story that isolated annual research or censuses cannot replicate. And just as important, GBBC is a wonderful way for anyone to feel connected to birds, nature, and being part of something bigger than themselves,” Bish said.

“Birds have a unique way of providing that entry-level interest in people,” she said, adding, “They are accessible and mesmerizing to watch.”

In sum, expand your knowledge and become a citizen scientist. You’ll enjoy it!

Bill Hobbs is a contributing nature writer for Estuary magazine and The Times of New London, CT. He can be reached for comments at whobbs246@gmail.com.