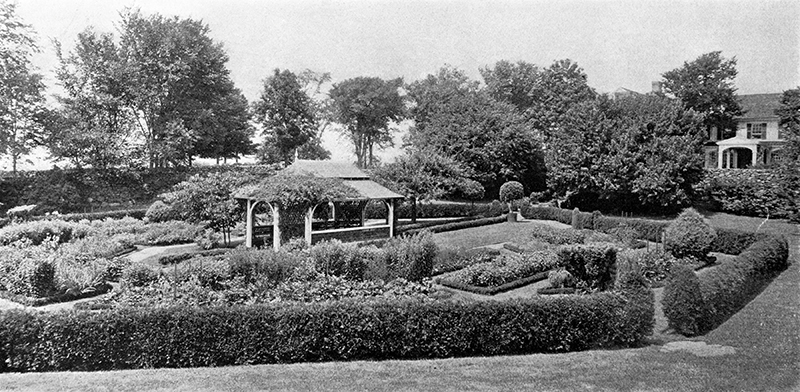

Flowers in bloom in the Sunken Garden with the main Hill-Stead house up on the hill in the background. mages Credits: Caryn Davis, Historical images Courtesy of Hill-Stead Museum

By Caryn B. Davis

The Tunxis Indians were the among the first people to utilize the land and the waters along the Farmington River, which were rich in wildlife, for hunting and fishing. In the early 1600s, the English settlers arrived. They soon discovered the fertile soil was suitable for farming, and the river made it possible to power the first grist mills and later sawmills and factories. The town of Farmington continued to grow and was incorporated in 1645.

By 1828, the Farmington Canal had been constructed. Merchants could now transport people and products by barge or boat to New Haven Harbor and up to Northampton, Massachusetts, bypassing the slower Connecticut River. But the canal system only lasted twenty years before it was replaced by the railroad. With the ability to move merchandise farther and faster, more factories sprang up, along with the need for housing and schools in what was quickly becoming a prosperous community.

Sarah Porter, an education reformer, established the prestigious Miss Porter’s School in Farmington in 1843 to foster the education of women. It attracted the attention of Theodate Pope, the daughter of wealthy industrialist, Alfred Pope, and his wife, Ada. Theodate left her home in Ohio at age nineteen to attend.

Grainstacks, White Frost Effect by Claude Monet from his haystack series hangs above a camelback sofa in the drawing room of the Hill-Stead Museum.

After graduating in 1888, Theodate accompanied her parents on a ten-month Grand Tour of Europe. She maintained a detailed diary during her travels, noting the buildings, farmhouses, artworks, and scenery that inspired her. She toyed with the idea of becoming an artist, but instead found herself drawn to architecture and declared it for her vocation. She convinced her parents to finance a retirement home that she would design for them on 250 pastoral acres they had purchased in Farmington.

Initially, her father engaged the services of the distinguished architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, designers of New York’s Pennsylvania Station, the Boston Public Library, and other notable buildings. However, Theodate insisted on leading the design process, and soon her doting parents acquiesced.

In the dining room, the two largest portraits are of Ada and Alfred Pope.

“While nearly all of the groundbreaking female architects born in the 19th century attended schools or universities to learn the trade, or at least received some form of formal higher education, Theodate simply took another path by engaging a professor at Princeton to serve as her private tutor in art history,” says Melanie Bourbeau, Senior Curator, Hill-Stead Museum.

(Ultimately, Theodate became one of America’s first female architects, designing an array of Connecticut homes and institutions, including the Avon Old Farms School, Westover School, and Hop Brook School.)

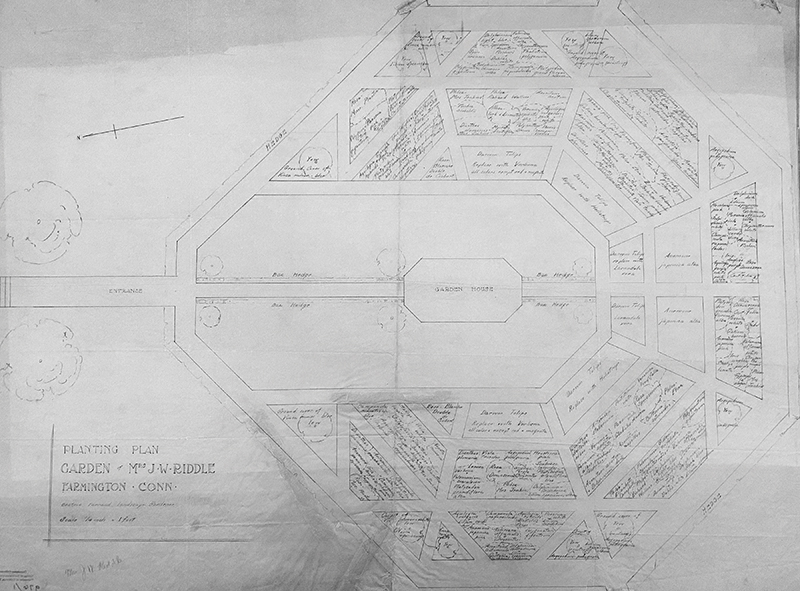

An old photo of the sunken garden from the Hill-Stead Museum collections. Above: Beatrix Farrand planting plan for the garden at Hill-Stead.

Theodate built a Colonial Revival home widely praised for its outstanding design. It was christened Hill-Stead because it was set upon a sloping hilltop. Staying true to her colonial aesthetic, the house was furnished simply, in comparison to the glitzy interiors of other estates from the same era. By this time, Alfred had amassed a sizable European and American art collection. He had become acquainted with impressionist art while on the Grand Tour where he purchased the first of three iconic grainstacks paintings by Claude Monet. (Two remain in the permanent collection and can be seen at Hill-Stead.) The textiles, colors, decor, and position of the furniture in each room were thoughtfully selected to complement the artists’ work that graced the walls.

When the house was near completion in 1901, Theodate focused on the property, adding vegetable gardens, greenhouses, and an octagonal sunken garden featuring 1,000 roses, with steps leading down to a gazebo or “Summer House” at its center.

Beatrix Farrand planting plan for the garden at Hill-Stead.

Hill-Stead was a place for Theodate’s family to entertain, and many prominent artists, writers, poets, politicians, physicians, and educators were guests, including the preeminent garden designer Beatrix Farrand. Farrand was one of the country’s first female landscape architects, and one of eleven founding members of the American Society of Landscape Architects, and the only woman in the organization. Like Theodate, Farrand was a trailblazer, and around 1920, she created a redesign of the sunken garden. However, it never came to fruition, and the existing garden was grassed over during World War II as labor and supplies dwindled.

In the 1980s the Connecticut Valley Garden Club and the Garden Club of Hartford decided to join forces to revive the garden and solicited the help of a New Haven landscape architect, Shavaun Towers, to lead the research and design effort. Towers utilized photographs from the museum archives along with topographical forensics to determine where the original garden beds had once been. But just prior to breaking ground, a museum board member discovered a newly published book about Farrand at a plant sale at Hill-Stead which just happened to be a fundraiser for the garden project. In the appendix was a listing indicating that one of her projects had been the “Residence of Mrs. J. W. Riddle, Farmington, Connecticut.” (Riddle was Theodate’s married name.)

“The landscape architect said the project came to screeching halt while they all regrouped, looking into this new source matter, and discovered the planting plan for the garden in the Farrand archives at the University of California, Berkeley. It was at that point the decision was made to implement the Farrand plan instead of what they believed the original garden layout to be,” says Bourbeau. “Farrand’s plan reflected her sensitivity to site-specific topography and proposed a more sophisticated planting scheme than the original garden. It seemed the most logical decision to make to use her design in lieu of a less notable garden plan that had once been extant.”

The garden has now been fully restored to its intended glory in accordance with Farrand’s original plan. It boasts 90 floral varieties in 36 beds in shades of pink, blue, purple, and white. This cool palette was Farrand’s preferred choice for much of her design work, and coincidentally complements the impressionist paintings on view indoors. The heirloom roses are still present, while heliotrope from the 1920s is grown for the Hill-Stead Museum in the greenhouses at Harkness Memorial State Park in Waterford, Connecticut. Today, visitors can wander the garden and sit in the gazebo as the Popes once did to escape the summer heat. In keeping with the Popes’s reverence for poetry and literature, the Hill-Stead hosts an annual Sunken Garden Poetry Festival featuring many Poet Laureates and Pulitzer Prize winners.

Before Theodate passed away in 1946, she had the foresight to establish a trust to turn Hill-Stead into a museum, which officially opened in 1947. She requested that all the contents remain in the house, and nothing new be added, so it would always look as it did when the family had been in residence.

For garden lovers, it is well worth the trip to Hill-Stead to overlook the vast fields and mature trees that define the property, walk the sunken garden’s paths, and experience Beatrix Farrand’s mastery of landscape design. But another reason to visit lies within the interior landscape where a world class art collection awaits. Whether it be one of Claude Monet’s View of Cap d’Antibes, or Edgar Degas’s Jockeys, these works—along with paintings by Manet, Cassatt, and Whistler, as well as sculptures by Barye, rare etchings, Japanese woodblock prints, and a vast array of rare books—are all on display. During a guided tour by a well-informed docent, visitors will be taken through many different rooms that have barely changed in 75 years. Best of all, Hill-Stead does not really feel like a museum, giving you the sense of walking through the Popes’s house while they are out for the day, but sure to return home in time for dinner.

For more information visit www.hillstead.org.

A view down into the Sunken Garden at Hill-Stead Museum.