Chapter 9: War

Here in Saybrook, we’re still adjusting to the idea that our new President, Abraham Lincoln, is calling up an army so he can preserve the Union and abolish slavery. It’s hard for us in New England to get used to being called, “The North,” let alone to imagine there is an actual fighting-war going on at all when the battlefields are so far away we can’t hear the gunshots or smell the mortar fire.

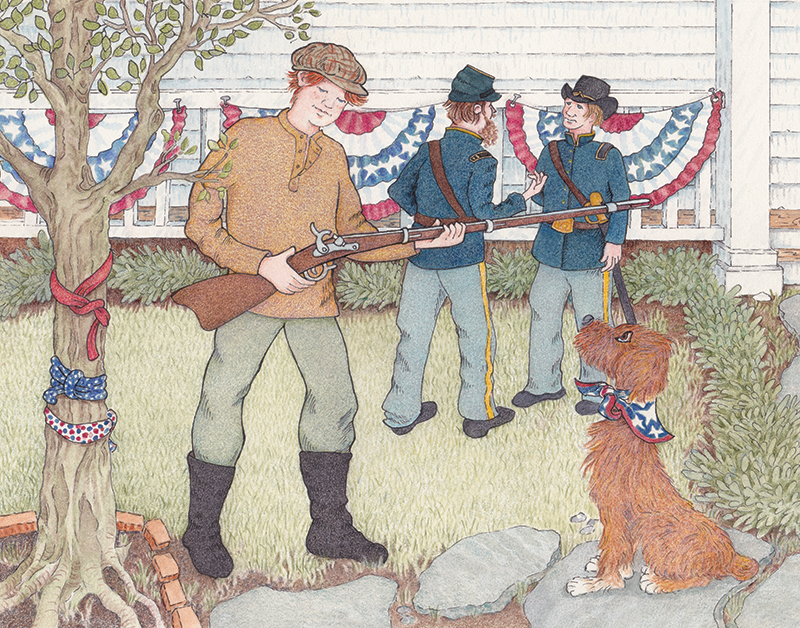

As soon as Cap sailed in from Lyme this morning, he secured the ferry to our dock and dropped the ramp, and I greeted the first man to step off. He wore a deep blue uniform jacket of the Union Army—my first time to see that uniform up close—and, boy, was his sharp. There were at least a dozen other uniformed men traveling with him. Cavalry, he said. They had left their mounts in Lyme and had come here to Saybrook today to “…march with the masses for patriotism…” Then he lifted his hat high over his head and finished up saying, “…for the Union!”

I stepped right up, saluted, and said, “Welcome to Saybrook. Sir.”

“Second Lieutenant Noyes,” he says to me, returning my salute.

I asked if I could follow along with him and his men today and offered my help if they should need anything.

“What’s your name, son?” he asked as we headed for town along the Shore Line rail tracks. Funny him calling me “son” since I took him for not much older than me.

“JJ, sir. JJ is easier to say than my whole name, which is Jeremiah Jedidiah, same as my father—he’s the captain of the ferry you just took across the river.”

Spit! Just like I always do, I gave too much of an answer. Sometimes a person will just turn and walk away when I talk too much, but the lieutenant let me finish what I had to say, and then he spoke to what was on his mind.

“I’ll tell you what you can do for me right now, JJ. We need a saw and a straight enough tree, not too tall, one we can use to fashion a flagpole—we’ll call it a Liberty Pole—so we can fly this fine ensign I was just given by a Mr. Babcock, across the river, in Lyme.”

“No need, sir,” I said, “Saybrook’s already got a big flagpole on the green.”

“I’m sure you do, JJ, but I know there’s is a certain group of men here in Connecticut who are sympathetic to the South. Secessionists. They’ll be expecting to fly their peace flag today, competing with the Stars and Stripes for space on that town flagpole.” He flashed a big old smile and said, “See, JJ, I figured if I put up my own flagpole, I can fly this fine Union flag.”

Lieutenant Noyes and I worked the crosscut saw together, felling a maple tree in just a few minutes, then a bunch of us worked with hatchets stripping the limbs, twigs, and suckers away from the trunk. Five or six men hoisted the tree trunk up onto their shoulders, and we all headed toward town and the green.

As we walked past the station, the doors of the train opened, and hundreds more men in all manner of blue uniforms poured out.

“Infantry,” Lieutenant Noyes said, giving me a little punch in the shoulder.

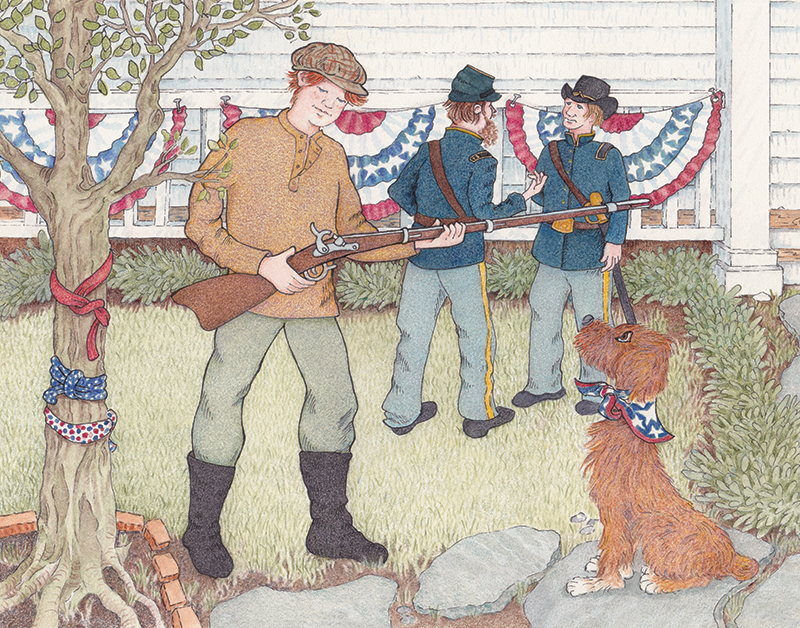

Most of the infantry soldiers carried a long rifle, a .58 caliber Springfield.

Lieutenant Noyes rushed up to a bearded officer who had just stepped off the train and said, “Sir! I remember you, sir. Aren’t you Captain Hawley? We were both at the battle of Bull Run, or First Manassas, as they like to call it down south. I’m Lieutenant Noyes, Cavalry. Glad to see you survived, sir.”

Captain Hawley told us the tale about how he survived. “Pretty good for an old man of thirty-five…” he said. He told us how mad he was when he heard that men were coming to Saybrook today to fly a white peace flag and speak out against Lincoln and the Union when men like himself were fighting and dying at Bull Run in the cause of preserving the Union. He held his rifle high and said, “I’ll take on any man who dares to speak treason against the Union.”

He lowered his gun, and with a fire still in his eyes, he looked directly at me and said, “How about you, son? You’re a strong and able looking young man. How old are you?”

“Fifteen, sir,” I said. “Sixteen before too long.”

“First Rifle Company A would be proud to have the likes of you in our ranks.”

“Am I old enough, sir?”

“The army is taking men fifteen to fifty,” he said. “Three months of service and you’re back here in Saybrook telling your family and friends about how you did your part to preserve the Union. What do you say—want to sign up? What’s your name?”

“JJ, sir. Does every fellow who signs up get that blue uniform? And a Springfield fifty-eight-caliber rifle like that one?”

He studies me for a minute, stroking his beard and squinting his eyes, the kind of look people get when they’re hatching an idea.

“Say, JJ,” he said, “you sure do know your guns. I might just want to put a story about you in my paper, the Hartford Evening Press.”

“A story with me in it? Spit! That would be fine, sir.”

“I’m organizing an infantry company. You’re just the sort of lad the Army is looking for. It would be a story about the caliber of fine young Connecticut men ready to serve. I might even introduce you to Governor Buckingham. You’d like that, I’ll wager.”

He was right about that. Here in Saybrook, we like to think of Governor Buckingham as one of our own, which puts us just one handshake away from meeting President Lincoln himself. We have it on authority that the Governor and the President are such close friends that Lincoln sleeps in Buckingham’s spare room whenever he’s passing through Norwich.

“It would be swell to meet the Governor in person, sir,” I said.

As I walked along with Captain Hawley, Lieutenant Noyes, and all the other soldiers, up to the green, I took a notion I was one of them.

I helped Lieutenant Noyes dig a hole. We tied Mr. Bradford’s flag to one end, then raised that maple flagpole, jamming a few big rocks into the hole to keep it secure. The reverend opened the doors of the Congregational church on the green, and the choir sang out America so loud I bet they could hear it all the way up in Essex. Hearing that patriotic music and looking around and seeing the red, white, and blue hanging from every porch rail, cart, and tree in Saybrook, made me feel proud.

The Peace flag crowd had their chance, too, with a speech or two, and the display of that white flag. But the assembly of hundreds who gathered here in Saybrook today left no question that the sentiments of the majority were on the side of Lincoln and preserving the Union. I asked Captain Hawley why we had to give the Peace flag people time to have their say and fly the white flag.

“Because Mr. Lincoln says that every man should have a chance to state his position, especially when we don’t agree with him.”

Captain Hawley let me examine his gun up close while he and Lieutenant Noyes carried on about the terrible turn of events at Bull Run and how the Union troops needed to win the next battle or old Jefferson Davis and his Confederate Army would get the idea they were winning this war.

Just as I was examining the Springfield up close, I hear my Mum’s voice.

“Jeremiah Jedediah! You put that weapon down before I draw another breath. I’ll not see a son of mine march off to war, carrying a weapon onto some god-forsaken battlefield on land he doesn’t know.”

“Cap? Why did Mum get into a huff when I was looking at Captain Hawley’s rifle? What’s she so mad about?”

“Not mad, son. Just worried. It’s a mother’s lot in life to worry about her children, especially when she comes upon the only child she’s got holding a weapon and in the company of Union soldiers.”

Cap told me he was worried, too, but that he understood why a man would take up a gun to defend his family, his home, and his country. He said when he was my age there wasn’t a war to join, but if there had been he might have answered the call. “But I had brothers and sisters,” he said. “You’re all we’ve got, son.”

I’ll wait until after we’re finished with supper tonight to tell Mum and Cap that I signed up with Captain Hawley today and joined the Union Army.

Historical Note

Joseph R. Hawley was mustered into the three-month 1st Connecticut Infantry with the rank of Captain. Hawley helped recruit an infantry company. Called upon to give a speech that day in Saybrook, he jumped up onto a wagon and said, “The word ‘peace’ must not be spoken until that disgraceful affair at Bull Run is wiped out.”

“This day’s gathering was without doubt the greatest assembly seen in Old Saybrook during this century.”

When Civil War demand for the Springfield .58 caliber musket/rifle (originally manufactured in Springfield, MA) exceeded supply, the Colt factory began production in its Hartford Armory. “Connecticut’s firearms industry achieved an unrivaled degree of success during the Civil War, manufacturing enough firearms to equip a large portion of the Union armies.”

–David J. Naumec, Arms historian

My thanks to the Old Saybrook Historical Society for their work in gathering material used in this series.