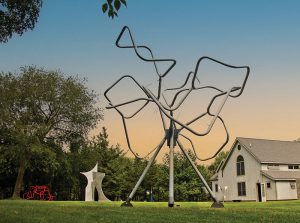

"After Fletch," sculpture by Gil Boro. Image Credit: Christina Goldberg

Made You Look

On our way to the Augustus Saint-Gaudens National Historical Park, my wife, Amy, and I cross the Cornish-Windsor Covered Bridge, the longest two-span truss bridge in the world, just as an ambulance flashes by and turns a beautiful architectural monument into a functional thruway. Still, Saint-Gaudens himself traveled across this bridge many times over the years and as an artist must have noted its profoundly sculptural form. Did it seem more beautiful to him because of its place on the river? Undoubtedly. Perhaps it influenced his own sculptures, as he worked each day in the hillside studio above. What does a river give to sculptures, to their spectators, and to the sculptors themselves? Or is it the other way around?

Aspet House at Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, New Hampshire. Image Credit: National Park Service, Public Domain

We continue driving up the forested hill, finding the park swamped with tourists, many here for a concert of traditional Abenaki music later in the day. We wander around the grounds, watching a hummingbird moth drink from the flowers in the garden, enjoying the mountain breeze that cools the summer lawns. People read on Saint-Gaudens’ porch and lounge in his water garden. At the visitor center is a heroic statue of Abraham Lincoln, standing up from a throne, framed by white birches and an ivy-covered concrete plinth.

Abraham Lincoln sculpture by Augustus Saint-Gauden. Image Credit: Eric Lehman

“That’s Abraham Lincoln,” one grandmother tells a small girl. “He’s the greatest American to ever live.” Of course, that isn’t honest Abe, despite the bushy eyebrows, stately beard, and sorrowful eyes. It is a sculpture. But maybe that is its magic; we relate to the object the way we relate to another being, in a full three dimensions.

In the spring of 1885, Saint-Gaudens and his wife took the train to Cornish in order to sculpt this monumental statue because his lawyer had told him that “there are Lincoln-shaped men in this area.” He had just finished his first big commission after years of working as a cameo-cutter, where he honed his incredible talent for precise and expressive work. He had only lived in cities, and his first view of the old inn that would become his house made him think of ghosts; he “immediately hated it.”

But the view of Mount Ascutney above and the Connecticut River below won him over. He named the property Aspet, for his father’s birthplace, and planted gardens, added porches, and built a succession of studios, including the huge 1904 high-windowed building where he made plaster casts and created a showroom for clients. “I was so enchanted with the life and the scenery,” he said. “I thought what a joy it is to come to the country.”

Other artists and friends began to spend time in the area, establishing the informal Cornish Colony, a node in the American Renaissance of art and letters. As commissions came in, assistants gathered at Aspet to help. Saint-Gaudens and his family spent a life surrounded by fellow artists, and surrounded by art inside their house—tatami and tapestries, busts and bas-reliefs, and a John Singer Sargent painting in the dining room. Today, this house and studio and sprawling property serves as a museum, with sculptures in the open air, available to all. A place to create or a place to display; this idyllic spot high above the Connecticut River has been both.

Clover Adams Memorial at Saint-Gaudens National Historic Park in New Hampshire. Image Credit: Eric Lehman

Lincoln stands in the sun, but hidden by the hedges is the shaded, hooded memorial for Clover Adams, who took her own life in 1885. The “original” of this statue rests with her in a cemetery in Rock Creek, Maryland. Nearby is one of several memorials for Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th, a bronze symphony that took fourteen years to complete. I have seen the “original” on Boston Common, and another “copy” in the Smithsonian, as well as smaller versions in other museums. After all, to cast a bronze sculpture only once seems strange to someone who spent years shaping it. And unlike someone else’s copy of a Van Gogh, these are all “originals.” The one on the Common is the “first” and this is the “final” form. Is it better in one place or another? In the bustle of downtown Boston or this quiet garden above the river?

"Pleiades" consists of seven twenty-foot-tall sails installed on two farm fields in Amherst, MA, for the Amherst Biennial 2010. Courtesy of Nancy Winship Milliken Studio

Whatever the case, none of these Saint-Gaudens works was necessarily created to specifically complement or interact with the Connecticut River itself. However, the small art gallery nearby does host a changing exhibit called “One River, Many Views,” which highlights the site’s relationship with the waterway below. Nancy Winship Milliken is exhibiting her sculpture in this gallery in 2023. Her “contemporary pastoralist” environmental and site-specific outdoor installations use natural materials like sheep’s wool and clay, which interact with the wind, sun, and rain. “Landscape with water is so much brighter—the light changes the work,” she says. “The water and the surrounding farmlands and estuaries are flat. It’s about the land around the water. The rolling hills, the waves of the hills. That’s what attracts sculptors like Saint-Gaudens.”

After earning an MFA from Massachusetts College of Art and Design in 2008, Winship Milliken has risen quickly to be an in-demand sculptor in New England, with solo and select group shows at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Boston Sculptors Gallery, Brattleboro Museum and Art Center, and many more. Her work perfectly demonstrates the journey that sculpture has taken since Saint-Gaudens, from representational to conceptual, from materials like bronze and marble to materials like wood and wool. “Saint-Gaudens was very much an artist of his time,” she says. “He strove to bring movement to his figures and bring them to life. A lot of artists still search for that.”

Milliken at work. Courtesy of Nancy Winship Milliken Studio

Winship Milliken’s own work is about process as much as it is about bringing life to objects. She uses sustainable and reclaimed materials, often cast-offs from cultural or artistic use, as a response to climactic and environmental changes. She finds or harvests these materials in their natural state, then molds, weaves, and burns them into form. “In our age, materials have changed—there are so many malleable ways of making sculpture now,” she says. “I use horsehair that changes with the movement of the wind. My sculptures are nature-centric, Saint-Gaudens’s works are human-centric.” In his memoirs, Saint-Gaudens agreed with this assessment of his work, saying, “To me, after all, Nature, no matter how superb, when it lacks the human element lacks the vital thing.”

Path of Life Sculpture Garden in Windsor, VT. Image Credit: Eric Lehman

Just across the river from the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site in Windsor, Vermont, the Path of Life Sculpture Garden seems to bridge these nature-centric and human-centric ideas. Walking past the Harpoon Brewery and the Silo Distillery, we enter through the “tunnel of oblivion” and can immediately see a fourteen-acre field of stone and wood sculptures. Each waypoint represents a point on the path of life, “accented by the Connecticut River.” A group of kayakers is getting ready to put in at the end of the field, while families walk along the Path of Life, part of the process, part of the sculptor’s intention. Nature here has become a metaphor for the human journey of life, much like the river itself.

“Amateur” sculptor Terry McDonnell and an occasional landscaping crew began this impressive work in 1997 by planting thirty red oak trees in “an arc that mirrored the gentle bend” of the river. Over the past two and a half decades, he has added to it piece by piece, from a large granite Buddha representing “Contemplation” to a fifty-foot-high bamboo circle representing “Forgiveness.” There are blueberries and prayer wheels, a hedge maze and a circle of giant wooden heads. This is bigger than sculpture, it is a “whole installation” that has a “cohesiveness of experience,” a landscape itself turned metaphor.

Although two sculpture gardens so close might seem an anomaly, the number of these installations and institutions in the watershed is astonishing in scope and variety, from the private but nonprofit Wickham Park in Manchester, Connecticut, to the public galleria in Riverside Park in Hartford to the private landscape designers showcase at Earthworks Garden in Leverett, Massachusetts. There are even more outdoor installations of various sizes at dozens of museums and hundreds of private studios up and down the valley. Some host residency programs, including Saint-Gaudens, which offers one for a sculptor every summer session in the Ravine Studio, just north of the Park’s lawns on the edge of a steep ravine. When we peek inside the clapboard-shingled cottage, a model of a skull sits on the desk, a project just worked on that very morning.

Three hours’ drive to the south on the Eight-Mile River in East Haddam, Connecticut, artists arrive from all over the world to a more wide-ranging residency program. With open-air and closed-studio laboratories for all the creative arts, including sculptors, I-Park encompasses dozens of natural and built environments prepared by artists-in-residence. The on-site exhibitions left by sculptors around the 450-acre campus often respond to and reflect the natural and constructed location. From a castle constructed of vegetation to an Ikea bed in a swamp, this unique place is both a wonderland for visitors and a sanctuary for artists to do their work.

One of I-Park’s more local resident artists, Bob Chaplin, has shown in indoor and outdoor galleries around the world, including on bluffs above the river in Farmington and Avon, Connecticut. His unique garden installations often harken back to the medieval “Hortus Conclusus,” controlled spaces as a protection from wilderness. One at I-Park that “commands the most interest and attention” is his Forbidden Garden, which uses poison ivy to protect a beautiful rose. “Staying there in a bucolic environment for a month with no distractions apart from the wind in the trees and the consistent bird song allowed me to explore new directions in my art,” says Chaplin. “The large meadow here provided a larger canvas for me to explore the role of invasive species and how they have changed our perception of the landscape.”

These sorts of outdoor spaces often serve as both installations and galleries for the sculptors. At the far south end of the valley, on the banks of the Lieutenant River in Old Lyme, Studio 80 and Sculpture Grounds uses juried competitions to provide a broad range of exhibitions of diverse sculptures. This town was once a center of American Impressionism, and the property abuts the Lyme Academy of Fine Arts, with a convenient path for students or visitors to take between the two. Studio 80 also hosts an annual exhibition that has featured the sculptural works of over 120 acclaimed artists.

"World Tree," sculpture by Gil Boro. Image Credit: Christina Goldberg.

Artist Gilbert Boro is the owner of this majestic property and the onsite fabrication studio. His sculptures are on display across the country, but many of the large-scale pieces are right here in this partially forested outdoor gallery, a few feet above the reeds and cattails of the river. He first received his degree from Duke before going on to complete advanced degrees from Columbia University. Over a long career he has worked with varied aesthetics and materials including wood, stone, metal, and fiberglass.

“I am an abstract sculptor,” says Boro. “I focus on the interplay of space, place, and form.” This is most obvious in his large, curving fiberglass labyrinths that seem to hang in space like strands of alien DNA. Though he respects the history of figuration and the importance of the human form, the scale of his sculptures is based on more than an object in space. “The sculpture becomes a space in and of itself to be fully explored with all the senses,” Boro continues. “My approach to sculpture is rather unconventional in that I encourage viewers to really explore the art—touch, feel, climb, walk through, or perhaps turn the piece. Utilizing all the senses changes the experience from being an observer to actually becoming a participant.”

Gilbert Boro. Image Credit: Christina Goldberg.

Many sculptors who create large-scale pieces have a difficult time displaying in ordinary galleries, so Boro wanted to share his Sculpture Grounds as a community space. Executive Director of Studio 80, Christina Goldberg, believes that the location on the river creates a unique, peaceful, tranquil atmosphere, noting that they carefully choose the artwork on the waterfront “to consciously mirror the same harmonious and tranquil energy the river radiates.” Working closely with the artists, they place the pieces to compliment or contrast the environment of the cedar grove, the grassy lawn, or the blooming garden. “Although the landscape is a masterpiece on its own,” says Goldberg, “displaying sculpture only adds to its allure by accentuating the natural beauty, bringing new perspective to the space and creating a brand-new place to be explored with all the senses.”

The combination of sculptures and landscape creates a unique sense of place for both artists and visitors. “There is something notably special about outdoor art,” Goldberg continues. “There seems to be a perpetual dialogue which happens between material, form, the way colors and surfaces change in the different light of day, and the ever-changing seasons.”

While Gilbert Boro’s coiling fiberglass and metal sculptures are in some ways built to stand the test of time, Nancy Winship Milliken has a different philosophy. She has exhibited up and down the watershed, but her temporary, natural material exhibits no longer wave in the wind in Amherst, Greenfield, Deerfield, or Northampton, where she used to live. “We are finite and this is my way of expressing life. I’ve learned to accept that I’m not the sole maker,” she says. “The environment has its say on the pieces, as it should. It’s almost like a theater piece, with characters that the environment transforms.” Indeed, this acceptance is something all artists must face, knowing that over centuries, even work in marble or bronze or steel will break down and fade. Nothing is permanent, not even the watershed’s landscape itself.

That impermanence is something many artists fight against, valiantly extending culture and ideas beyond their lifetimes. Others, like Winship Milliken, try to accept it, allowing sun, rain, heat, and cold to continue her work. She cites Eleanor Robinson’s idea of “celebratory ecology,” wherein ecology “calls each of us to spend time outdoors, and observe colors and movement, presences and absences of species, and yes, to simply enjoy the bounty. We celebrate ecology and are all inspired to do all within our power to protect and learn about this essential life-giving ecosystem.” How can art achieve that? After exploring the sculpture gardens of the Connecticut River Valley, the answer seems obvious.

At Saint-Gaudens on that sublime summer evening, my wife, Amy, and I sit on the lawns with a crowd of a couple hundred people, listening to Abenaki music echo off the pergola of the artist’s studio and out into the endless air. A huge thornless honey-locust planted by Augustus himself looms over the house. Across the river is Mount Ascutney, sculpted by wind, water, and time. Should we see the tree and mountain as sculptures, too? After all, our human sculptures—whether conceptual or representational, whether built into the landscape or separate from it, whether built to last one year or a thousand—might inspire us to see everything in three dimensions as art, maybe even the river itself.

Gil Boro studio manager and lead fabricator Bryan Gorneau at work. Image Credit: Christina Goldberg.

“I haven’t been thinking about sculpture all day,” says Amy as we leave, echoing my thoughts. “I have been interacting with the land. It was great to see Saint-Gaudens pieces there, but I found myself equally as fascinated by the tree bark and the hummingbird moth.” As we drive down along the river, I embrace this perspective and begin to see sculptures in every church spire rising from each village we pass, every rusted car and rock wall, every cattail and reed.

“What sculpture should do is make you look,” says Amy, pointing. “There’s one with a heron sitting on it.” I stop and stare, but see only a piece of driftwood, shaped and moved there by the Connecticut River. Who is the sculptor now?