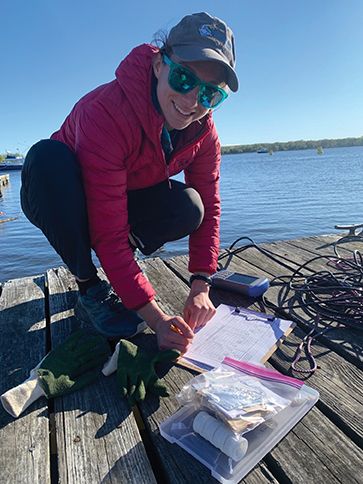

Concluding her morning outing after testing the water

quality in seven locations along the Connecticut River. Image Credit: Estuary

Five a.m. Streaks of soft pink light the predawn sky. It’s late June, and I’m on my way to Essex to meet Kelsey Wentling, a river steward with the Connecticut River Conservancy.

Mist is rising from the river as we both arrive—nearly simultaneously—at the Connecticut River Museum, our launch site. Kelsey has driven all the way from her home in Northampton, Massachusetts—an hour-and-a-half journey. Yet, even at 5:30 in the morning, she’s energetic, organized and eager to get to the day’s task: testing water quality at half a dozen spots along the river.

As she pulls gear from her car, she tells me about her mission. She is one of several river stewards measuring the algae and chlorophyll content, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, salinity, and water temperature at intervals all along the 400 miles of the Connecticut River. She’s been doing this job—among others—for three years—after getting a master’s degree in Environmental Science from UMass, Amherst. Her assignment today involves mapping the test sites on her GPS, drawing water samples into a long test tube, and recording her findings for submission to a database that tracks the health of the river. The work has to be done within a couple of hours after sunrise, before the water temperature and contents are affected by sunlight. She makes the trip from Northampton twice a month between April and October. With a smile she admits it’s easier when the sun doesn’t rise so early.

By the time Dick Shriver (Estuary’s publisher and a licensed captain) arrives and we’ve made our way to the boat the museum has made available to us, the mist has turned to a dense fog. It envelopes us utterly as we don jackets and head out on the river on a northerly course, Dick at the helm. Waves slap against the aluminum hull. But all other sounds are muffled. Kelsey, undaunted, consults her GPS and confers with Dick, who tosses out an anchor when we’ve reached our first stop. Kelsey checks her equipment and lowers the sizable test tube into the water, careful it’s at the desired depth. She works with purpose, gracefully mocking herself as she struggles with the electronics of water-testing. When she brings the test tube up, she records the data on a clipboard. She seems pleased with the numbers.

Quite quickly we’re off to the next site. Kelsey’s sights are on her work, not the pea soup fog, though I peer into it hoping to spot the shoreline or a buoy or anything that might tell me visually where we are. When Dick heaves the anchor overboard at the next stop, we can just barely make out the boat landing at Ely’s Ferry. The sun is rising and beginning to burn off the fog.

Kelsey readying the the “water probe” (or “sonde”) for its descent to the river bottom. Image Credit: Dick Shriver

We head south, along Nott Island, sampling as we go. Then west toward Hayden’s Point. We spot ospreys and a bald eagle as blue sky replaces the fog. Now, with a grin, Kelsey points toward a boathouse at the waterline south of us. “I’d love to live there,” she tells me. Understandable. It would suit her.

At twenty-eight, Kelsey has the trim figure of the marathon runner and Ultimate Frisbee player she is. She also has the confident bearing of a young woman who’s given a lot of thought to what she wants in life and believes herself to be on the right track.

She points again, this time to a sleek motor launch anchored in front of the boathouse. A Hinckley picnic boat? A Billy Joel? Whatever it is, it’s handsome. “I’ve told so many people I’d like a ride that someone promised me an introduction to the owners.” She’s laughing at herself, clearly showing a more playful side. But her focus returns to the work as we reach the last test site in the shallows south of the Essex Yacht Club.

As we make our way back to the museum dock, she tells me she makes a separate trip every two weeks to drag the bottom of the river for signs of subsurface invasives and to kayak on the scout for colonies of water chestnut, which also threatens the river’s ecology and economy.

I am struck by her devotion to her job, her impressive knowledge, her unaffected demeanor, her can-do attitude. She’s already told me that she hopes and expects soon to add advocacy—lobbying, reviewing permits and regulations, helping forge legislation to protect and preserve the river—to her portfolio of tasks.

But Kelsey is not to the river born. Her childhood years were spent in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and for a time, Manhattan. How can it be that she has immersed herself so deeply and determinedly in the Conservancy’s mission to prevent pollution, improve habitat, and promote enjoyment of the river from source to sea?

“It’s important work,” she tells me. “It’s my highest priority—the natural world and our place in it. My job is both meaningful and enjoyable.” She goes on to say that, as a child—the next-to-youngest of six siblings— she spent a lot of time outdoors. But it wasn’t until high school, in Stonybrook, New York, that she took a course in environmental science and began to focus. College at the University of Delaware was a revelation. “I couldn’t believe we have all these problems and aren’t doing enough about them.”

She also credits her summer vacations on Cape Cod as part of her inspiration. For two weeks each August, she and her family rent a rustic cottage right on the beach. Swimming, kayaking, rowing, biking, and other seaside pleasures fill their days and reinforce Kelsey’s belief that the natural world is where she wants to be.

Is it a lifetime commitment? Kelsey hesitates. “I want to see a better river,” she says. “I want to engage more people, give them more access to and knowledge of the river. Make people feel safe and welcome on the river.” And how to do that? “By enhancing water quality. So that native fish can return. Salmon used to be in the river, but now we find only one or two per year.”

Kelsey with US Sen. Blumenthal at a

Connecticut River Conservancy gathering to raise awareness of non-native invasive plant life at the federal level. Image Credit:Judy Preston

“Water chestnut,” she goes on, “looks like lily pads. But it alters the habitat, the temperature of the river. The result is a monoculture. Eliminating it is a significant issue.” Why? Because of the health of the river, “and the economic impact,” she adds. “Property values go down. Tourism, marinas, recreation are all impacted.”

So, it isn’t only idealism that motivates Kelsey. Both the practical realities and “the human dimension” are at the core of her ambition.

And where does she see herself in five years? “I don’t know,” she answers. “I’m constantly learning in this job. I want always to work where I’m still learning.”

I think about those words as I watch her launch her kayak at Ely’s Ferry. She heads northward along the riverbank, searching for water chestnut and making a difference to the river with every dip of her paddle.