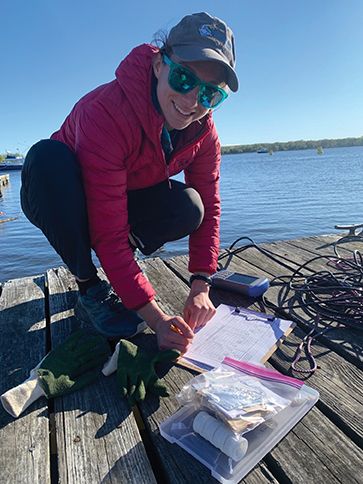

Concluding her morning outing after testing the water

quality in seven locations along the Connecticut River. Image Credit: Estuary

Five a.m. Streaks of soft pink light the predawn sky. It’s late June, and I’m on my way to Essex to meet Kelsey Wentling, a river steward with the Connecticut River Conservancy.

Mist is rising from the river as we both arrive—nearly simultaneously—at the Connecticut River Museum, our launch site. Kelsey has driven all the way from her home in Northampton, Massachusetts—an hour-and-a-half journey. Yet, even at 5:30 in the morning, she’s energetic, organized and eager to get to the day’s task: testing water quality at half a dozen spots along the river.

As she pulls gear from her car, she tells me about her mission. She is one of several river stewards measuring the algae and chlorophyll content, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, salinity, and water temperature at intervals all along the 400 miles of the Connecticut River. She’s been doing this job—among others—for three years—after getting a master’s degree in Environmental Science from UMass, Amherst. Her assignment today involves mapping the test sites on her GPS, drawing water samples into a long test tube, and recording her findings for submission to a database that tracks the health of the river. The work has to be done within a couple of hours after sunrise, before the water temperature and contents are affected by sunlight. She makes the trip from Northampton twice a month between April and October. With a smile she admits it’s easier when the sun doesn’t rise so early.

By the time Dick Shriver (Estuary’s publisher and a licensed captain) arrives and we’ve made our way to the boat the museum has made available to us, the mist has turned to a dense fog. It envelopes us utterly as we don jackets and head out on the river on a northerly course, Dick at the helm. Waves slap against the aluminum hull. But all other sounds are muffled. Kelsey, undaunted, consults her GPS and confers with Dick, who tosses out an anchor when we’ve reached our first stop. Kelsey checks her equipment and lowers the sizable test tube into the water, careful it’s at the desired depth. She works with purpose, gracefully mocking herself as she struggles with the electronics of water-testing. When she brings the test tube up, she records the data on a clipboard. She seems pleased with the numbers.

Quite quickly we’re off to the next site. Kelsey’s sights are on her work, not the pea soup fog, though I peer into it hoping to spot the shoreline or a buoy or anything that might tell me visually where we are. When Dick heaves the anchor overboard at the next stop, we can just barely make out the boat landing at Ely’s Ferry. The sun is rising and beginning to burn off the fog.