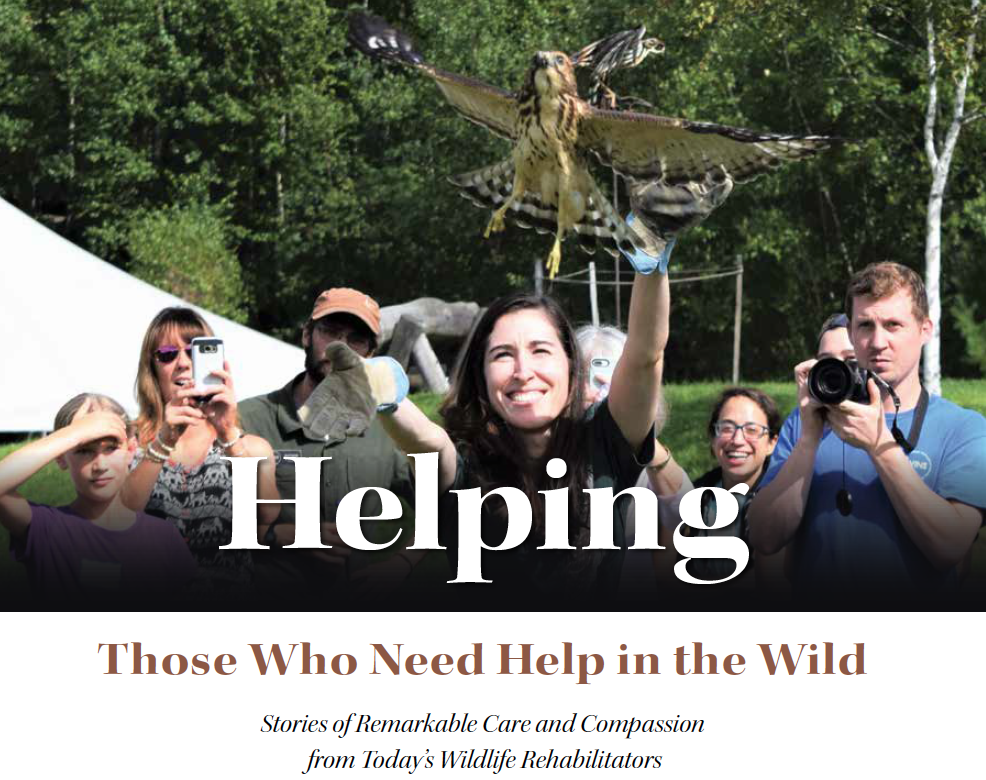

Grae O’Toole, releasing a rehabilitated raptor back into the wild. Image Credit: Courtesy of the Vermont Institute of Natural Science

By Bill Hobbs

How many times have you seen an injured animal or bird and wanted to assist it, but didn’t know where to turn?

The good news is there are wildlife rehabilitators in each state. And you can locate them by Googling either “animal rescuers” or “wildlife rehabilitators” or by calling your local authorities.

It takes a very special person to answer that call. A person who is committed, caring, knowledgeable and has a deep commitment to helping animals, mammals, birds, and other wildlife who can’t help themselves during their time of need.

Wildlife rehabilitators would think nothing of spending a few sleepless nights nursing a small songbird with cuts and abrasions back to health. And once that bird gets back on its feet, they would then go the extra mile to release it in the exact same place, or close to where it was originally found, “because it is a known territory for them, and it’s the best way to set them up for success,” one rehabilitator explained.

Indeed, many wildlife rehabilitators operate out of their homes, paying out of their own pockets for most of their supplies, medicines, and holding cages. They are often self-taught. To date, there are no formal degrees offered in wildlife rehabilitation; only online or in-class accredited courses are available. In fact, the National Wildlife Rehabilitators Association recommends a degree based in biology or ecology, with a curriculum that includes ornithology, mammalogy, or animal behavior, if one wishes to pursue this career.

Further, most wildlife rehabilitators are highly specialized, caring for either mammals, birds, reptiles, or amphibians. They must be state licensed, and they are deeply committed to temporarily caring for injured, sick, or orphaned animals, rehabilitating them so that they can be released back into the wild.

Debbie Datilio, a retired registered nurse, fits that description perfectly. Specializing in small mammals, Datilio has a practice in Lyme, Connecticut, called Gift of Time Wildlife Rescue. During the last fifteen years, she has successfully worked with and helped release back into the wild over 100 skunks, 200 opossums, and countless squirrels and rabbits.

Datilio with two of her baby opossums. Photo Credit: Bill Hobbs

But on the morning of May 1, 2022, Datilio got a call that she won’t soon forget.

The night before, Sheila and Myra Amsdenfish, from nearby Waterford, Connecticut, sped in their car past a large, dead opossum and thought it looked odd—freshly struck by a car, and possibly still alive.

They stopped, went back to the inert animal, picked it up, and found it was a pregnant female, clearly dead. But she had twelve tiny joeys, or baby opossums, still alive, suckling in her pouch.

“Sheila and Myra did all the right things,” Datilio later said. “They removed the joeys from the mother’s pouch, kept them warm overnight (with a heating pad), and contacted me in the morning.”

When Datilio received the joeys, she weighed them. Each weighed an ounce. Then she tube-fed them a clear electrolyte solution every two hours for the first four feedings to flush their system and hydrate them. Then she started a weakened formula and gradually worked up to full strength, every three hours around the clock for the next four days.

“I was a bit bleary-eyed for the first few days,” Datilio admitted. “But it takes time for wildlife to get over the hump, after intake, so rehabbers are in this ‘hover mode’ until they stabilize the animals.”

Debbie Datilio weighing one of twelve joeys (baby opossums) under her care. Photo Credit: Bill Hobbs

Three months later, with lots of care, ten of the twelve opossums survived for release. “It is so rewarding to be able to give them a second chance to live their wild lives,” explained Datilio. “Rescuing, rehabbing, and releasing our native wildlife back to the wild has occupied a special place in my life for the past fifteen years, and I’m thankful to have moved to a community here in Connecticut that values its wildlife as much as I do,” she said, adding, “We rehabbers couldn’t do it without the support of our caring communities.”

There are many other rehabilitators that are equally as committed. Grae O’Toole, for example, is the director of the Wild Bird Rehabilitation Center at the Vermont Institute of Natural Science, or VINS, in Quechee, Vermont, a nonprofit environmental education, research, and avian rehabilitation organization. Their stunning 47-acre campus, which is open to the public year around, features live bird programs, raptor enclosures, interpretive nature trails, a spectacular new Forest Canopy Walk, and educational programs.

In 2021, O’Toole said the center admitted 1,098 songbirds and raptors—some with terrible injuries—and successfully returned more than 43 percent—or 470 rehabilitated birds—back into the wild, a result that was no small feat.

O’Toole said that unfortunately many birds are brought to the center with injuries too serious for them to survive or have any quality of life and must be humanely euthanized. Of course, these events are heartbreaking for any rehabber, O’Toole said, but they take solace in every one of their successes, as well.

What’s Grae O’Toole’s favorite part about being a wildlife rehabilitator?

“It’s saving lives and the initial problem-solving stages that I find most rewarding,” said O’Toole, who has a degree in biology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “No day is ever the same. There’s always a new bird, with a new challenge, and each day is always consistently inconsistent, which is what I love.”

Barry Genzlinger and his wife, Maureen, are two more individuals who answered the call to become wildlife rehabilitators. In 2015, they founded the Vermont Bat Center, in Milton, Vermont, to provide information and educational programs about bats to individuals, schools, and other groups, and to support the rescue and rehabilitation of injured and orphaned bats throughout the Green Mountain state.

When the pandemic hit, the Genzlingers and everyone else who handled bats had to follow strict COVID protocols, dictated by state officials. They had to wear masks, gloves, and gowns; work in a sterile environment; and have minimal contact with the animals. At one point, Barry said they had to use test kits and send blood samples to Tufts University and await negative results, before they could release any bats back into the wild. Why?

“The fear was that when COVID first hit, we humans, who are traveling around the world, would bring COVID back [to the US] and introduce it into the North American bat population,” Genzlinger said.

Thankfully, over time, Genzlinger said state officials eased their restrictions, allowing bat rehabbers to release bats without COVID tests.

“I spent fifteen years learning all I could about bats and bat houses through my association with Bat Conservation International and the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department, and my wife has graciously come along for the ride!” said Genzlinger, who taught math in high school for eighteen years and then ran a successful software company, before getting into wildlife rehabilitation.

What’s most rewarding about rehabilitating and releasing bats for Genzlinger?

“Our biggest reward is being able to get out in the public and talk to people about bats and their value to the environment and try to dispel the notion that has been beaten into them for the last sixty years by the entertainment industry that bats are evil, they come out at night, eat people, and all have rabies, which isn’t true,” he said.

Finally, Molly Gezella-Baranczyk, executive director of the National Wildlife Rehabilitators Association, told me wildlife rehabilitators need our help with donations. Communities do not typically fund wildlife rehabilitators, and almost everything comes out of their own pockets.

She said, “Listen to what they are telling us, because wildlife rehabilitators are the best source to help that animal survive in the wild.”

Bill Hobbs is a contributing writer and columnist for Estuary magazine. He lives in Stonington, CT, and can be reached for comments at whobbs246@gmail.com.