From the Publisher:

Great American Outdoors Act

The Pondicherry Division of the Conte Refuge. Image Credit: David Govatski

Passage of the Great American Outdoors Act (GAOA) in 2020 was greeted enthusiastically by those who enjoy nature and the outdoors. The new legislation has two components. The first part “established the National Parks and Public Lands Legacy Restoration Fund.” This fund, “supported by revenue from energy development, provides up to $1.9 billion per year for five years to make significant enhancements in national parks and other public lands, ensuring their preservation and providing opportunities for recreation, education, and enjoyment for current and future visitors.” The second part guaranteed permanent, dedicated funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), calculated as a portion of fees from oil and gas leases. This will provide at least $900 million per year for the entire country. These funds will support “increased access to state and locally owned outdoor recreation opportunities; creation or expansion of national trails, parks, and forests; preservation of working lands (e.g. private farms, forests, and ranches); preservation of historic or cultural sites; development or rehabilitation of urban parks; and conservation of wildlife habitat.”

I wanted to know how much of the latter might benefit our watershed. Subsequently, I researched the history of this act and spoke to several experts on the matter.

Congress created the Land and Water Conservation Fund in 1964. This monumental legislation was a bipartisan commitment to safeguard natural areas, water resources, and our cultural heritage, and to provide recreation opportunities to all Americans. Thanks to federal funds from LWCF, every one of our fifty states touts special places for Americans to enjoy, including national wildlife refuges such as the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge; national parks like Acadia National Park and the Great Smoky Mountains; national forests; rivers and lakes; coastal areas; community parks; trails; and ball fields. Every year, $900 million in royalties—paid by energy companies drilling for oil and gas on the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS)—are put into this fund.

Unfortunately, Congress only fully funded LWCF once in its 55-year history, so a longtime goal of the conservation community was to ensure that its yearly-promised $900 million be appropriated. In 2020 this was achieved with the passage of the Great American Outdoors Act, which finally ensured that LWCF funding would be guaranteed for conservation and recreation every year.

GAOA 2-year anniversary celebration in Old Lyme, CT. (L to R) Joyce Leiz, COO Connecticut Audubon; Kristen Sykes, Director of S. New England Conservation Projects and Partnerships, Appalachian Mountain Club; Ned Lamont, Governor of CT; and Claudia Weicker, Board Chair of Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center. Image Credit: Alisha Milardo of the RTPEC

Kristen Sykes, Appalachian Mountain Club’s Southern New England Director of Conservation Projects and Partnerships and Advocacy Chair for the Friends of Conte, focuses on the four watershed states of New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. She notes that there is a huge need for LWCF funding for the Connecticut River watershed and that the Conte Refuge could spend $15 million or more per year on land conservation projects throughout the four states for the foreseeable future. In addition to land acquisition projects, LWCF also funds trails, playgrounds, and community gardens in watershed cities such as Holyoke, Springfield, and Hartford.

Amy Lindholm, the Appalachian Mountain Club’s LWCF Coalition Manager, notes that the watershed has $40 million in project opportunities waiting for LWCF funding for FY23/24. In Lindholm’s view, the GAOA is the “most significant conservation legislation in 25 years,” but still more funding is needed. The LWCF Coalition, which Lindholm represents, has 1,000 member groups nationwide.

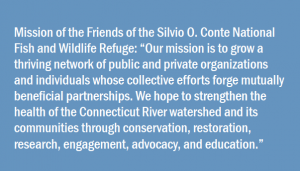

Similarly, a coalition of organizations representing the Connecticut River watershed is the Friends of the Silvio O. Conte Refuge (FOC). As noted on their website: “The Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge was established in 1997 to conserve, protect, and enhance the abundance and diversity of native plant, fish, and wildlife species and the ecosystems on which they depend throughout the 7.2 million-acre Connecticut River watershed.” The FOC is comprised of more than 70 public and private member organizations that represent a wide variety of mission-compatible interests, such as the Appalachian Mountain Club, Mass Audubon, Audubon Vermont, the Connecticut Audubon Society, Farmington River watershed Association, Friends of Pondicherry, Kestrel Land Trust, Trout Unlimited, the Springfield Museums, and The Nature Conservancy. FOC is an informal, all-voluntary group started in 2005.

Markelle Smith, who works for Mass Audubon and chairs the Executive Committee of the FOC, states that the “LWCF will now have more money for Refuges, including the Conte Refuge, and by extension for the partners who collaborate with Refuge staff on land acquisition projects in the watershed.” Conte has regularly received from $0 to $6 million each year from the LWCF but received $17.2 in FY 2022: $5 million from the LWCF, plus an added $12.2 million in one-time “earmarks” for specific projects sponsored by specific legislators and passed by Congress. Smith adds, “the Connecticut River watershed has it all: rural, suburban, and urban communities adjacent to the river, as well as floodplains, intact forests, and wetlands…. Conte and the Connecticut River watershed can be a national model for collaboration between all scales and types of organizations advancing conservation.”

Many have recognized the importance of the FOC as a collaborating collective of organizations with overlapping missions. The value of such collaboration has been proven, by the LWCF Coalition’s legislative success, FOC’s advocacy for the watershed, and partnerships on the ground to achieve land protection goals: more than 40,000 acres have been protected in the watershed because of LWCF. Such was the case with the Fannie Stebbins Unit of the Conte Refuge. This land was saved for posterity by a collaborative effort between The Nature Conservancy; the town of Longmeadow, Massachusetts; the Allen Bird Club; the Natural Resources Conservation Service; and the Conte Refuge, among others (see Estuary magazine, Spring 2020: “A Treasured Refuge Becomes Permanently Protected—An Environmental Success Story”).

David O’Neill, President of Mass Audubon, opines that the newly appropriated LWCF funding offers “enormous hope of motivating others. It’s a moment we can’t miss.” With O’Neill at the helm, the Mass Audubon board has committed to fund two years of a limited staff for FOC. This is big news for the watershed, as it has been a recognized need for some time.

Dick Shriver

Publisher & Editor