The Holyoke Dam, seen from Vietnam Veterans Memorial Bridge, creates the reservoir in the Connecticut River to feed the Hadley Falls hydroelectric generating facility, at left, in Holyoke, MA. Image credit: Christopher Zajac.

On a fine spring day in May, a morning mist rises as snowmelt from the peaks of Vermont and New Hampshire spills over the long slope of Holyoke’s granite dam. Just downstream at Slim Shad Point, a band of anglers shields their eyes from the rising sun, casting lines into the rapids. A few are already proudly taking their shad to the headquarters at Hadley Falls Station to be weighed for consideration in the HG&E (Holyoke Gas and Electric) Shad Derby.

Anadromous fish who pass this gauntlet of sportsmen and sportswomen are drawn away from the dam and into the Robert E. Barrett Fishway by an attractive water flow system. A gate closes and machinery whirrs to life. The migrating fish begin what is, for them, the strangest part of the journey: an elevator ride to the top of the dam. They wait patiently as they rise, while fascinated tourists watch them through the windows of this moving aquarium. In the exit flume, the fish are individually counted—hundreds of thousands every year—before swimming into the still, flat waters beyond.

Above the power station, past the maze of canals and fleet of brick factories, the smokestacks and spires of the Paper City shine vermillion in the dawn. On the other side of the river, a pair of intrepid canoeists has portaged and is putting back into the stream, perhaps heading for Springfield or even all the way to Old Lyme, Connecticut. This is the last point boats cannot pass on the Connecticut, and they will have smooth paddling from here to the estuary, eighty-six miles south.

The viewing room at the Robert E. Barrett Fishway at Holyoke Dam in Holyoke, MA. Image credit: Courtesy of HG&E.

The current Holyoke Dam—once a waterfall with a fifty-three-foot drop at the north end of a sharp bend in the Connecticut River—is the third to be built at this location. In the 1840s George C. Ewing marked this peninsular site as a great spot for an industrial city. After purchasing 1,200 acres, and with an investment of four million dollars, the Hadley Falls Company began to build the first dam during the summer of 1848. This timber dam filled with rubble and stone was the second longest in America, and the proud engineer remarked, “There! Those gates are shut, and the God Almighty himself cannot open them!”

He spoke too soon. By the afternoon of that day, the dam was leaking, and at 3:20 p.m. the whole structure collapsed. According to Arthur Ferry’s recollection decades later, “Many people were walking about, picking up shells and relics, until warning was shouted that they were in danger, and then there was a lively scramble to get to safety….[E]specially do I remember Mr. James H. Clapp. He was a portly man and came struggling and puffing up the bank, and seeing my father and Mr. Ebenezer Warner, he reached out his hands and cried frantically, ‘Devil, Devil, Warner, help me up!’”

The Robert E. Barrett Fishway is at left alongside the outflow from the Hadley Falls generating station in Holyoke, MA. Image credit: Christopher Zajac.

An editor of the Springfield Republican, J. G. Holland, remarked that “Strong hearts trembled within them, and every face was pale at the sight. The labor of many minds and hundreds of hands for a long summer—the pride and confidence of the contractors, just in the hour of triumph were swept off in an instant, and naught but the huge wreck that remains is left to tell of the mightiest structure of the character, that was ever built in this country.”

View of the great dam, Holyoke, MA. From South Hadley Falls/J. Bowker lithograph, Published by Harvey H. Cragin, ca. 1868. Image credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Not to be deterred by this engineering failure, the company constructed a second dam a year later, built 1,017 feet long with four million feet of timber. It was again “built with the wrong face up stream,” according to the Engineers Club of Philadelphia, but unlike the previous dam, it held firm. Still, vibrations caused by the dam assailed the surrounding buildings for almost two decades until an apron was built that solved that problem. A greater problem of erosion remained, and the worthies of Holyoke called again and again for a new dam throughout the final years of the 19th century. At last, a new dam was commissioned in 1895, and with the help of the longest cableway in the world, stones were set into place. It was finished five years later on January 5, 1900, the longest stone dam in the world at the time.

The purpose of these successive dams was to create power for the textile mills, machine shops, and paper mills of the growing manufacturing city. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, immigrants from Ireland, Quebec, and Germany arrived to work and live in Holyoke’s brick factories and boarding houses, including twenty-three paper mills that produced 150 tons of paper per day. In 1877, John McCormick tested his Hercules turbine here, and eleven years later perfected the McCormick-Holyoke turbine, with double the output of the previous waterwheels. The “Venturi meter” that measures flow was also designed and tested here before being marketed commercially in 1889.

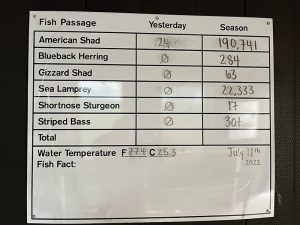

A board at he Barrett Fishway with a running count of migrating fish. Image credit: Courtesy of HG&E.

In the early 21st century, Holyoke Gas and Electric took over the dam and canal system, providing two-thirds of the city’s annual electricity. Two hydroelectric generating wheels on the west bank of the river produce thirty-three megawatts of power. The Canal System provides water to ten in-service generating stations that produce another seventeen megawatts, using the drops between canal tiers to use the same water up to three times for electrical production. The State of Massachusetts named Holyoke a Green Community, and the high-speed fiber optic network, solar panels, and hydroelectric resources drew the Massachusetts Green High Performance Computing Center to Holyoke in 2012.

“The City of Holyoke was founded on innovation and sustainable practices, when industrialists were drawn to the natural drop in the river in the mid-to-late 1800s. HG&E is proud to uphold these values as the current owner of these historic assets,” says Steve Roy, Electric Superintendent for HG&E. “We are a municipal utility, managed locally, which puts us in a unique position to make decisions based on the needs of the community and our ratepayers.”

“There are advantages to having a facility like the Holyoke Dam be part of a municipal utility,” says Andy Fisk, who is both a Holyoke resident and president of the Connecticut River Conservancy. “The license terms reflect best practices, and so we have a facility that is operating under best practices for hydropower.” Those procedures include a new rubber crest that tops the dam, and a weir on the canal that protects endangered mussel species during draining periods. Upstream habitat is also safeguarded by minimization of water level fluctuations.

The canal gatehouse at left, controls water flow into the canal system, in the foreground, in Holyoke, MA. The Holyoke Dam is in the background behind the concrete wall. Image credit: Christopher Zajac.

As the first and most successful fish lift on the Atlantic coast, the 1955 Robert E. Barrett Fishway and elevator lift has long been a key part of the dam’s conservation efforts. But what might be the most exciting part of the lift is also more recent. Federally endangered shortnose sturgeons became a focus of concern since they faced injury risks from the turbines and had to be removed by hand out of the fishway. Working with the Conte Laboratory, the state of Massachusetts, and the National Marine Fisheries Service, the municipality reengineered parts of the fish ladder to prevent large fish like sturgeons from swimming through the turbines, completing the work in 2016.

“HG&E has done an amazing job on sturgeon passage with some really cool engineering to get sturgeon up and down stream for the first time since the dam was built,” says Fisk. “They worked very hard on that, and it represents a very important milestone for this federally endangered species.” The sturgeon seem to like the change, with more appearing in the lift than ever before. Indeed, the migration of shad, herring, striped bass, sea lamprey, and even Atlantic salmon not only keeps anglers busy, but they also keep the river ecosystem healthy and strong.

“We are focused on balancing renewable, hydroelectric energy generation with the protection of valuable natural, cultural, and scenic resources,” says Steve Roy. “We are proud of our efforts to protect various species and habitats along the Connecticut River and continue to partner with various stakeholders to carefully balance energy production and environmental needs within the community.”

In other places throughout America, dams have been targets of environmentalists and anglers alike. To some critics, the balance between the community’s needs for energy and needs for healthy waterways seem inevitably mired in conflict. As perhaps the most prominent “bottleneck” on the Connecticut River, the Holyoke Dam could be one of those flashpoints. But by adapting to new economic and social realities, this dam has somehow weathered almost two centuries and seems poised to weather a third.

At noon, the sun shines directly on the dam, dazzling the water with amber light as it cascades over the dam’s smooth, sloped surface. Families linger at the fences of the Hadley Falls Canal Park, and cars slow down on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Bridge to watch this phenomenon. It is undeniably beautiful, even to the eyes of the most hardened conservationist. Can a dam be more than a source of sustainable power? Can it actually be a work of art? The Holyoke Dam may offer an answer.