That’s how proprietor Jon Cohen characterizes aptly named Deep Meadow Farm, nestled in a picturesque valley between the 3,144-foot Mount Ascutney and the Connecticut River in the village of Ascutney, Vermont. With more than fifty acres of rich river bottom soils permanently preserved for agricultural use, the property represents a critical resource central to the Connecticut River watershed’s heritage and identity.

When I visited Deep Meadow Farm on a late spring day, colorful rows of vegetables lined many of the fields. Cohen and several of his fifteen employees—multitasking while overseeing activities on a busy morning—graciously provided a tour and overview of the property. They cycle the crop fields—which are spread along a half-mile of river frontage but not flood-prone—through the growing season. Six greenhouses propagate tomatoes and other vegetable seedlings, bedding plants, and flowers. A year-round operation, the farm produces hardy greens such as kale and spinach, in heated greenhouses and hoop houses, and stores harvested root crops during cold months.

When I visited Deep Meadow Farm on a late spring day, colorful rows of vegetables lined many of the fields. Cohen and several of his fifteen employees—multitasking while overseeing activities on a busy morning—graciously provided a tour and overview of the property. They cycle the crop fields—which are spread along a half-mile of river frontage but not flood-prone—through the growing season. Six greenhouses propagate tomatoes and other vegetable seedlings, bedding plants, and flowers. A year-round operation, the farm produces hardy greens such as kale and spinach, in heated greenhouses and hoop houses, and stores harvested root crops during cold months.

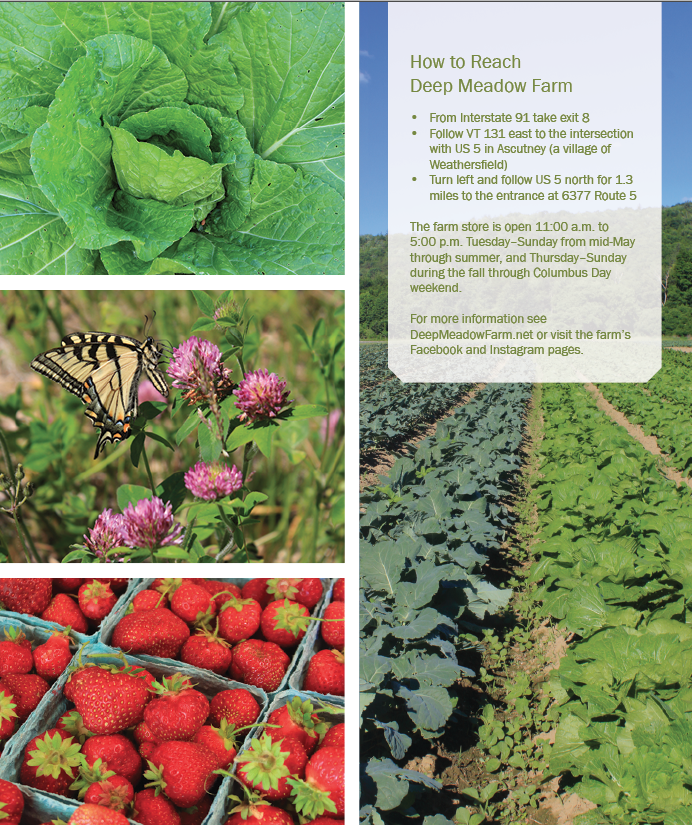

Deep Meadow Farm’s diverse assortment of products include strawberries, lettuce, tomatoes, squash, potatoes, and other certified organic vegetables and fruits, herbs, and flowers. The farm also offers poultry, eggs, and meat, which are raised consistent with organic standards but not certified. Harvested goods retail at a variety of local and regional markets, including wholesale distributors throughout the eastern seaboard, food establishments, seasonal farmer’s markets in Woodstock, Ludlow, Londonderry, and Brattleboro, and the farm’s on-site store, which is open from May to October. Loyal customers obtain produce through a buyer’s program, similar to a traditional Community Supported Agriculture arrangement, that provides flexibility and value for members while generating beneficial early-season income for the farm.

As we walked along a freshly planted field, Cohen, who has farmed the Connecticut River for more than twenty years, detailed characteristics of the farm’s “Windsor loamy sands.” Ideally suited for high-yield vegetable, fruit, corn, and tobacco crop propagation, Windsor soils are excessively deep, well-drained, and permeable. Their sandy texture and low water retention capacity necessitates frequent irrigation, however, with water pumped up from the Connecticut River in Deep Meadow Farm’s case.

First classified in an 1899 soil survey and named for the town of Windsor, Connecticut, Windsor soils occur throughout the Connecticut River Valley, with greatest acreage in the northern portion of the watershed. They represent the former floor of glacial Lake Hitchcock, which once stretched for 140 miles from present-day Rocky Hill, Connecticut, to Newbury, Vermont (roughly sixty miles north of Deep Meadow Farm). When it drained at the end of the last ice age about 11,000 years ago, the former lake bottom became a valley with deep, rich soils, enhanced by subsequent alluvial and wind deposits, that support some of the nation’s most productive agricultural land.

In historic times, the valley’s rich soils—a crucial resource for Native Americans and colonial farmers—influenced settlement of towns and brought considerable prosperity to the region. Roughly 220,000 acres of the watershed’s rich soils are still actively farmed (about 3 percent of the total watershed area). Most of the prime land lies in the southern portion of the watershed, but the Connecticut River valley soils in Vermont and New Hampshire are among the finest in those states.

In historic times, the valley’s rich soils—a crucial resource for Native Americans and colonial farmers—influenced settlement of towns and brought considerable prosperity to the region. Roughly 220,000 acres of the watershed’s rich soils are still actively farmed (about 3 percent of the total watershed area). Most of the prime land lies in the southern portion of the watershed, but the Connecticut River valley soils in Vermont and New Hampshire are among the finest in those states.

Organic certification ensures that farm products are grown and handled in a sustainable and safe manner, using practices that protect and cycle natural resources, promote ecological balance, and sustain biodiversity. Although certification is optional, has no effect on farm income, and increases labor and potential crop losses, Cohen feels it is important for the big-picture health of the environment. The USDA implemented federal certification in 1990 to establish consistent national organic standards for growers and consumers and to prevent fraud.

Deep Meadow Farm’s sustainable management practices include use of mineral and animal-based fertilizers and environmentally safe pesticides. Cover crops such as red clover or winter wheat, plants that are grown specifically to protect and improve soils and future crops, provide numerous benefits such as erosion mitigation, enhancement of organic matter, and control of weeds, pests, and diseases. Beehives and flowering plants sustain pollinating insects, which are crucial for food production and crop yields; pollinators such as bees and monarch butterflies have declined significantly worldwide due to habitat loss, pesticide use, and other factors.

Cohen and his partner acquired the property in 2012 though Vermont Land Trust’s (VLT) Farmland Access Program, which provides opportunities for farmers to purchase or lease affordable land. Since 1977, VLT has preserved 158,000 acres of farmland (about 2.5 percent of the area of all of Vermont) and used federal, state, and private funding sources to protect the site, a well-known local landmark that had not been actively farmed for years.

After VLT issued a request for proposals, Cohen’s bid was selected out of a competitive group of applicants based on his strong business plan and prior experience running a successful farm. Acquisition of the land provided space to grow a greater variety of crops and raise animals.

After VLT issued a request for proposals, Cohen’s bid was selected out of a competitive group of applicants based on his strong business plan and prior experience running a successful farm. Acquisition of the land provided space to grow a greater variety of crops and raise animals.

VLT holds a permanent conservation easement on all of the land apart from a seven-acre homestead, which allowed the property to sell for approximately half of what would otherwise be its market value. If Deep Meadow Farm or any similarly protected property goes up for sale in the future, VLT retains the right to review prospective buyers to ensure the land continues to be productively used for agriculture. As Cohen puts it, “the land’s value is not as a money-making investment, but for growing food.” Other land trusts in the Connecticut River watershed offer similar options for farms and prospective buyers.

Permanent protection of places like Deep Meadow Farm is crucial for maintaining the Connecticut River watershed’s rapidly declining agricultural land base. Despite productive soils, the region’s farmers face numerous challenges, including global market competition, rising land values, development pressure, and climate change effects.

Permanent protection of places like Deep Meadow Farm is crucial for maintaining the Connecticut River watershed’s rapidly declining agricultural land base. Despite productive soils, the region’s farmers face numerous challenges, including global market competition, rising land values, development pressure, and climate change effects.

According to a report by the Trust for Public Land, more than 25 percent of the watershed’s farmland was lost between 1982 and 2002 alone, and just 11 percent of the prime soil acreage was protected as of 2006. The American Farmland Trust has listed the Connecticut Valley as one of the country’s most threatened important agricultural regions. Farm preservation ensures continuity of local food sources, strengthens community economies, preserves scenic and historic landscapes, and provides open space benefits such as wildlife habitat and flood control.

At the end of the day, I stopped by the farm store, where employees reported an active sales day for strawberries and other produce. Such community support further increases the viability of locally owned family farms. In the words of Deep Meadow Farm’s website, “In an effort to become secure in our future, it is essential to restore local sources for food. We invite you to go beyond putting food on your table and join an important movement that will restore the sovereign control of our food to you.”