From the Publisher:

On My Mind...

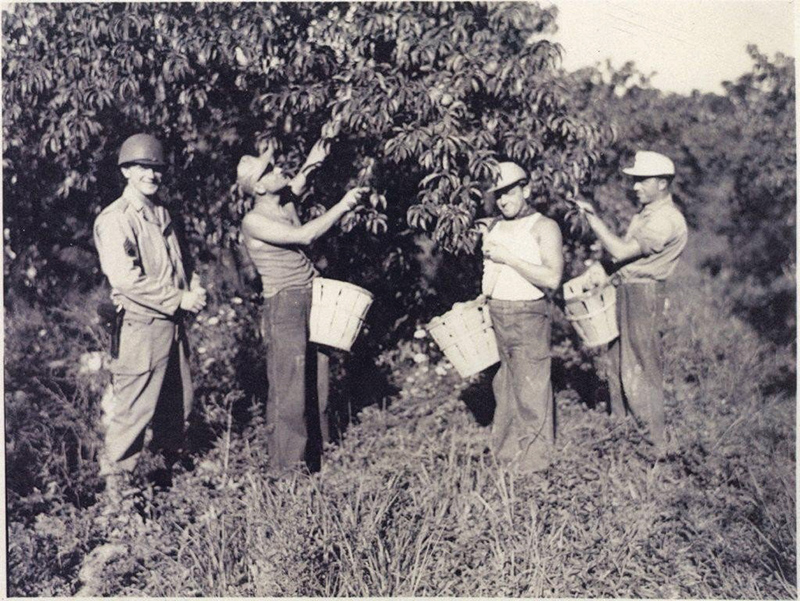

Three German POWs and a US Army guard picking fruit on a Maryland farm in 1944. Image Credit: Courtesy of the Howard County (MD) Historical Society where the original is housed in its archives.

Dick Shriver

Publisher & Editor

My father operated a farm in Maryland in 1944 and planted five acres of string beans, all to go toward the war effort. As anyone with a garden can tell you, five acres is a lot of beans and, at some stage, will require a lot of pickers. Pickers were paid by weight, and at the end of the day, my mother drove the farm truck loaded with sacks of beans down to the Baltimore harbor. From there, we were told, the beans were shipped to the western front. One interesting aspect: most of the beans were picked by German prisoners of war (POWs) camped at the Fifth Regiment Armory in Pikesville. Being eleven years old at the time, I was also conscripted to pick beans alongside these mostly young soldiers who arrived each day in the back of army trucks. We were all paid at the same rate. The Germans so they could buy cigarettes, and my cousins and me so we could buy lemon phosphates at the local drug store. A coveted prize at the time was a POW’s cap lying on the roadside having blown off in the wind as they passed by.

While WWII was raging, a philosophical battle was also on the rise involving what at the time appeared to be extremist views to many. William Vogt published his seminal book, Road to Survival, in which he advocated for population control, since the planet could provide, in his opinion, food and other resources for only a limited number. Fairfield Osborne wrote Our Plundered Planet, in which he argued that people are more likely to destroy themselves in conflict with nature than by any weapons of war, such as desecration of the soil through—among other mechanisms—bad agricultural practices. At the time, the world population was just over two billion.

The world didn’t just survive; its population grew to nearly eight billion today. One person often credited with avoiding mass starvation and malnutrition-related diseases along the way was Norman Borlaug. According to some, Borlaug saved the lives of a “billion” people. This plant pathologist perfected a strand of wheat, for example, that not only had an abundance of kernels, it also had a shorter, stronger stem capable of carrying the weight of those extra kernels through all kinds of weather.

The results of those philosophical debates in years past are playing out in the Connecticut River Watershed today in a multitude of ways. Here is what we see. Fish for human consumption and for the survival of other forms of wildlife are being restored, in some cases with the hope of approaching pre-colonial levels. Water quality throughout the watershed has greatly improved over the decades and today is monitored routinely, though much work still remains to be done. The sharp decline in bird populations and numbers of species in North America generally has been reported, and its impact in the watershed is being tended to in various ways: pollinator and rain gardens are growing in number, for example, and ways to construct them are being widely promulgated. Large nonprofit agencies and many dozens of land trusts and associations are working to preserve and conserve land and to sustain ecologically-appropriate uses. To offset the loss of trees to development, better forest and tree management practices are being introduced. Family farms are being managed better from an ecological standpoint and are being deeded into perpetual farm use in lieu of housing developments. A premium is placed on projects that provide for environmental equity and justice in urban areas. Tens of thousands of trees are being planted each year to mitigate the impact of flooding. Many wildlife species are being counted regularly for purposes of identifying troubling or encouraging trends. “Buying local” is an increasingly popular theme consistent with healthier food and combatting climate change. Thousands of children each year are provided with instruction, examples, training, and hands-on research to inspire good stewardship of the watershed’s resources. Federal and state agencies are collaborating with private and nonprofit groups to the advantage of the entire watershed. Untold numbers of volunteers contribute via annual cleanups and other activities. Growing numbers of families are enjoying the pleasant nature of the Connecticut River Valley and tributaries via stand-up paddleboards, canoes, rowing shells, kayaks, hiking, biking, and camping.

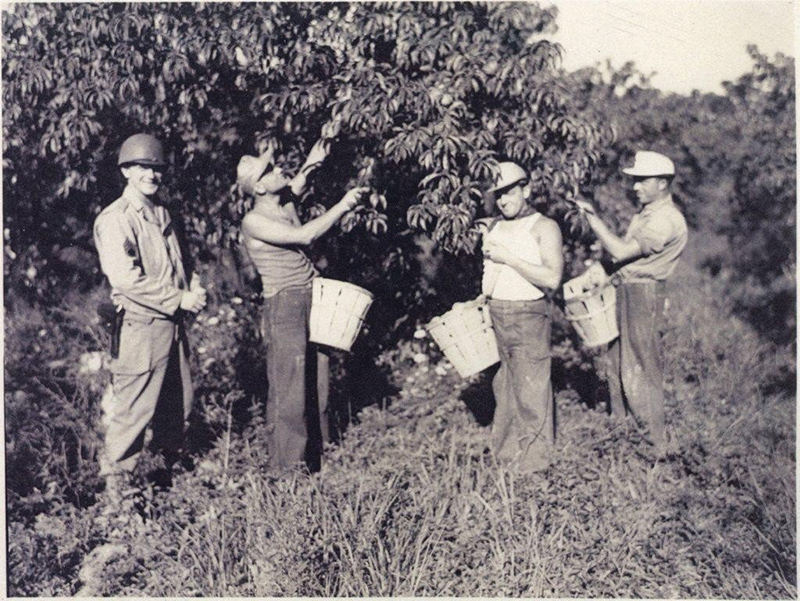

Driving through the Vermont countryside last year, we spotted Jon Cohen’s Deep Meadow Farm. What caught our eye were the long rows of colorful vegetables on the dark, flat, alluvial deposits from geological history of “Windsor sandy loam,” earth that allows water to penetrate easily to the roots of plants (as contrasted with Pennsylvania red clay, e.g.). It just looked both prosperous and well-managed by a good steward of its natural resources. John Burk’s subsequent article herein proved us right.

Deep Meadon Farm. Image Credit: John Burk