Chapter 7: A Railroad Bridge

I asked my teacher at the Academy, Reverend John, if I could go to the Town Hall meeting tonight, the one about the new railroad bridge, and then write about it for my essay assignment.

“As long as you don’t favor one side or the other, JJ.”

“But, Reverend John, I do favor one side,” I said

“Then that will be the hardest part for you, JJ, won’t it?”

It looked like everybody in Saybrook was at the Town Hall meeting tonight. When news got out that a representative from the New Haven & New London Railroad would come here to answer questions about the new railroad bridge. I guess we all wanted to hear what he had to say. Mariners, from here to Hartford, were pretty steamed up about building a bridge.

Captain Otis who runs the steam rail-ferry Shaumpishuh stood up and spoke first. He pointed toward the ceiling. “Mark my words, the day we watch a train pass over the Connecticut River on a bridge, from Saybrook to Lyme, will mark the beginning of the end for our way of life here on the river. Pretty soon, horses, carriages and carts, wagons, and people will demand a bridge of their own. And what will become of Saybrook and the Shaumpishuh? And me? And my family? Ferrying the train cars across the river—that’s my livelihood.”

“Sell the Shaumpishuh for scrap,” a commercial shad fishermen offered.

“Not as long as I draw a breath,” Captain Otis shouted back.

The railroad representative, sitting up there in the front row, stood and turned to face all the rest of us. “The train will stop in Saybrook,” he promised, with a big smile. “You have my word. Your taverns and inns all along the waterfront will get more business than ever, you’ll see. The smaller ferries will carry on as always.”

“Saybrook will turn into a place people glance at out their train windows at as they pass us by,” my father said, more to himself than the room.

“Bridges are a danger to navigation. Period!” Ray’s father shouted.

Then the railroad man got serious. No more smile. “I’m here tonight because I need you to promise me that what happened eight years ago when we tried to build a bridge in this same spot, won’t happen again,” he explained.

“For those who don’t remember, it was 1852 and the New Haven & New London Railroad had just initiated services. We’ve got the same problem today that we had back then. When the train gets here to Saybrook, it has to stop. The engine is decoupled and the cars have to be ferried across the river on the Shaumpishuh to Lyme where they’re rolled off, connected to a new engine, and continued on to New London.

“No offence, Captain Otis, but that ferry connection has always caused delays. A railroad bridge will eliminate those delays.”

“And, eliminate my job!” Captain Otis shouted.

“A lot of truth in what Otis says,” the tavern owner said, nodding.

The railroad man continued. “Eight years ago, we proposed to build a covered, hand-turned, wood swing drawbridge between Saybrook and Lyme. That bridge would have left enough of an opening when the bridge was open for a whole fleet of warships to sail up and down the river two by two. ‘Prove it!’ you all shouted. So, we planned a demonstration. We anchored two sailing ships facing upriver, one on either side of the opening of the proposed swing drawbridge.

“Just like tonight’s meeting, that day was pitched with a great political fever. The people in favor of a bridge gathered here, on the Old Saybrook side of the river, and those against a bridge over on the Lyme side. Both sides tried to out-do each other, flying banners and offerings of free food and drink.

“Finally, it was time for the Shaumpishuh to sail up the river through the opening of the drawbridge. People in favor of the bridge gave up loud cheers when the rail-ferry did just that, passing between the two sailing ships with plenty of room on both sides. The Shaumpishuh continued upriver a bit, turned around and sailed back down the river. On her second approach to the opening, however, something happened. I was told that a sudden and powerful current grabbed onto the Shaumpishuh and pulled her off course,” he said, looking directly at Captain Otis.

“That’s exactly what happened,” Captain Otis said. “That current pulled the Shaumpishuh toward Lyme, smashing broadside into one of the two sailing ships. There was nothing I could have done. That sailing vessel sank to the bottom of the river while we all watched.”

“As a consequence, that bridge was never built,” the railroad man said.

“And yet, your railcars have continued to be ferried across the river to this day,” Captain Otis said. “No need for a bridge.”

The railroad man stood up, gathered his papers, put on his hat, and spoke in such a way as to say that this debate has ended. “When this new bridge is finished,” he said, all smiles again, “more passengers will be able to travel to New London in half the time, and you, Captain Otis, can find easier work on a regular passenger steamboat. It’s progress, my good man. Progress.”

I spent the next two days after the town meetings tagging along with Captain Otis and the New Haven railroad man, so I could, like Reverend John said, “Gather first-hand information from both sides of the debate for my essay.”

“Welcome aboard the Shaumpishuh, JJ,” Captain Otis said. “Weather’s not the best today, but you being a ferryman yourself, you’re no stranger to wind and chop.”

He handed me a pair of heavy leather gloves and said, “Wear these. Avoids rope burn.”

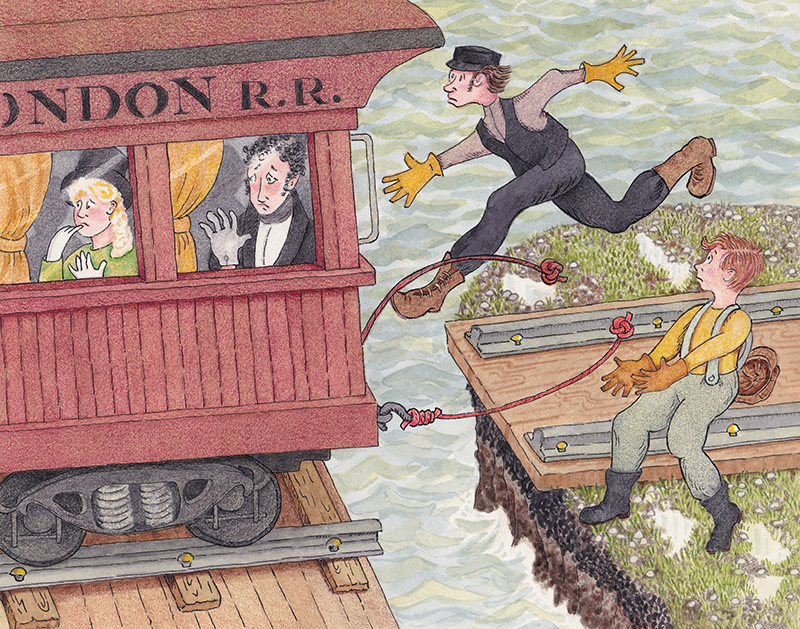

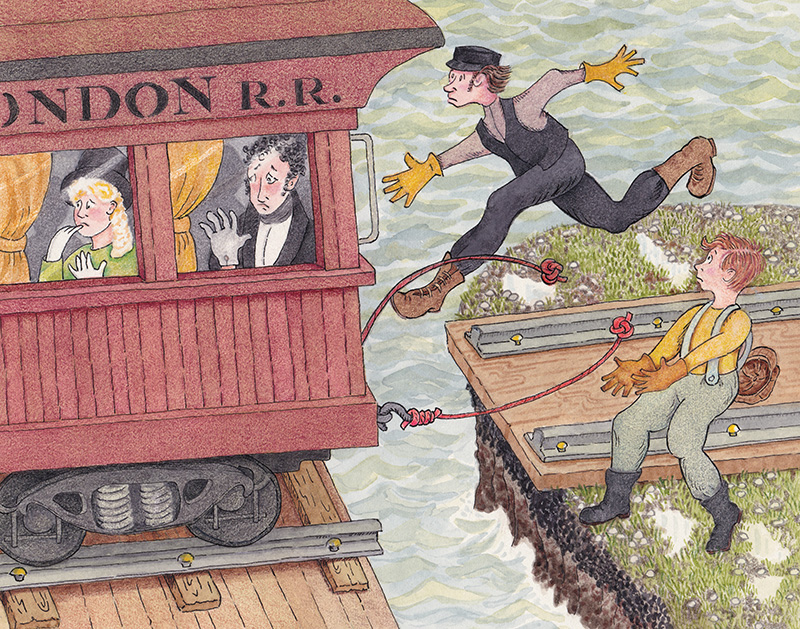

As the wind came up, the Shaumpishuh fought to hold steady alongside the dock. Captain Otis and I stood on either side of the ferry ramp and held fast to guide ropes attached to the first passenger car. Those passengers who dared look out their windows to witness the operation took on a wild-eyed look. The river rose and fell with no particular rhythm.

“Now!” captain Otis shouted, and we pulled the guide ropes until the first passenger car’s wheels rolled onto the ferry rails. A sudden swell raised the rail-ramp and both passenger cars rolled onto the ferry, nice as you please.

We secured the passenger cars to the ferry with chains, fore and aft, and set out to steam our way across the river to Lyme. The train car doors were opened, and the passengers were invited to eat and rest in one of the two cabins alongside the passenger cars, but because of the rough waters, most stayed in their seats for the hour or two until the captain announced we were arriving in Lyme.

Captain Otis lined up with the rails on the Lyme ramp, but the ferry kept moving up and down with the river making it hard to match up the rails with the dock ramp. We grabbed the guide ropes and pulled with all our might. The two passenger cars were almost fully off the ferry when the Shampishuh dipped down into the backside of a big river swell. Captain Otis dropped his guide rope and did a flying leap back onto the ferry. The guide rope flew out of my hands and both cars rolled back onto the ferry with a mighty clamor, and screams from inside the cars. For a minute I thought those cars were rolling so fast they might just keep going out the other end of the ferry and into the river. I bet that’s what the passengers were thinking, too. We finally got those cars off, attached to the waiting engine, and on its way to New London.

The railroad man didn’t have any chores for me to do. He fed me tea and lunch at the bridge-building site on the Saybrook side of the river. He showed me how the new covered, swing-draw railroad bridge was being built of the strongest and finest lumber money can buy. “The foundation,” he said, “is as strong as the pilings that have held up the whole city of Venice for a thousand years.” Then he went on to tell me about the ancient builders and the monuments, cathedrals, aqueducts, even bridges they built that are still standing today. “This bridge is being built in the tradition of all the great builders,” he said.

Turns out, my essay wasn’t about a debate between two sides. I wrote instead about how things just keep moving ahead, even if we’re not ready to move ahead ourselves. Progress either hits us over the head with logic, or waits, enjoying a long nap under the apple tree until we catch up.

For several years, the new railroad bridge experienced a series of delays and unexplained accidents. Finally, the first railroad bridge opened in 1870, sixteen years after it was first proposed. However, the engineer and his crew abandoned the train at the last minute out of fear of the new bridge collapsing, so the principal bridge builder saved the day and drove the train across the new bridge and into the future.

The Shaumpishuh rail-ferry served the New Haven & New London Railroad Company from 1852 to 1870.

Charles Dickens, on his 1868 tour of America, wrote about his experience crossing the Connecticut on the Shaumpishuh. He wrote about “he whole train being banged aboard a steamer” and about the cars breaking loose from the guide ropes: “the carriage rushed back with a run downhill into the boat again.”