Image Credit: Getty Images/WilshireImages.

It’s hard to believe that a tree could save a democracy, but according to legend, that’s exactly what happened when Sir Edmund Andros arrived in the Connecticut colony in 1687 to collect the royal charter given to the Puritan settlers by King Charles II in 1662.

Why was this particular piece of parchment so important? When the Puritan settlers traveled from Massachusetts to create a colony in the wilderness along the Connecticut River in 1636, they had no official authorization to do so. Under the leadership of Rev. Thomas Hooker, they established a General Court that bound the settlements of Hartford, Windsor, and Wethersfield together to keep order, but it was not a formal document. In 1639, they created the Fundamental Orders, a written covenant based on the consent of the governed. It began with a preamble, followed by eleven orders that gave all governing power to the General Court (one of the reasons Connecticut is so litigious), with the right to elect deputies and magistrates given to the freemen or electors.

Many of us feel that this is the first written constitution, conceived and executed before John Locke even went to school. Connecticut is the Constitution State because of the Fundamental Orders. They allowed the colony to govern itself without interference from the crown.

The colony had been established during the reign of Charles I, who was usurped by Puritan Oliver Cromwell and his forces, naturally pleasing Puritan leaders in the colonies. When the monarchy was restored under Charles II, Connecticut sent John Winthrop Jr. to England to smooth things over and negotiate a charter. The charter, known as the Warwick Patent, consolidated the New Haven colony with Connecticut, extended the boundary of the colony to the Pacific, and gave the colony a considerable amount of freedom.

When James II followed his brother Charles II, Sir Edmund Andros was sent to create the Dominion of New England under greater control of the crown. Andros began collecting all the colonial charters, which is where the story of the Charter Oak comes into play. Remarkably, Andros arrived at the colonial meeting house in Hartford on Meeting House Square on Halloween, October 31, 1687. During that “negotiation,” wrangling apparently went on all day into the evening when candles were needed, but, according to legend, all the candles were snuffed at the same time. When the lights were relit, the charter was gone.

The story continues that Captain Joseph Wadsworth absconded with the charter and carried it off to the tree. By 1687, this great white oak had seen centuries of life go by from its perch overlooking the Connecticut River. It’s distinctive position on the Wyllys estate made it a standout on the landscape, a short ride from the meeting house in the village. Who would suspect a tree would be used as a hideaway for the most important document in the colony?

The Charter Oak was a magnificent white oak. Connecticut’s main forest tree is the oak, divided into the red oaks and the white oaks, the reds having pointed leaves and the white having lobed. When Andros arrived, most of the leaves on other trees were probably gone from their branches, but oaks hang onto theirs into the spring of the following year—a bane to those who like a well-kept yard—but important ecologically for all the critters that rely on the oak. This leaf-holding phenomenon is known as marcescence; beeches are also marcescent.

Still having all those leaves provided extra cover for the crevice where the charter would be nestled until it was safe for it to mysteriously reappear. The other twelve colonies were not so lucky, making Connecticut’s the only extant colonial charter in existence! More than a hundred yeas older than the Declaration of Independence.

Image Credit: Getty Images/AlexanderZam

In appreciation of the job the Charter Oak performed, the tree became hallowed ground, beloved across the new state for the rest of its existence and down to present day. The city grew around it, but it was set off in a vacant lot on the South side of Charter Street not far from Main Street. The grand old tree stood for almost two hundred more years before she was blown over on August 21, 1856, during a severe storm.

The entire state mourned her loss, coming to visit the giant fallen relic, probably the most important warrior for independence in the land. The Colt Armory Band came to play, and church bells all over the city tolled for the savior of freedom.

To memorialize her passing, every part of the fallen giant was gathered up, cataloged, stored for the future, some of it at the Connecticut Historical Society. Fortunately, she had already set fruit, leaving a mass of acorns to assure her progeny. Chairs were made, one for the president of the state senate. An ornate frame was carved to house forever the Charter she cradled so long ago, which you can see at the State Museum of Connecticut History in Hartford. The Wadsworth Atheneum also has items from the tree on exhibit.

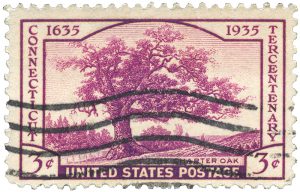

The Charter Oak was apparently so important to Lydia Sigourney, known as the “Sweet Singer of Hartford,” that she published a ballad in the 1840s where she described the massive oak as “ancient and fair.” She again memorialized the Charter Oak with a poem when the grand old monarch fell. There are at least five paintings of the Charter Oak, including one by native son Frederic Church, but the one by Charles De Wolf Brownell appears to be the one used for the 1935 Connecticut commemorative half dollar, as well as the tercentenary stamp. The tree was again memorialized on the 1999 Connecticut quarter of the 50 States Series.

The Charter Oak’s legacy lives on. Over the years, there have been the Charter Oak lawn mower, the Charter Oak Bridge, Charter Oak Park, Charter Oak State College, Charter Oak Federal Credit Union, and now Charter Oak Brewing.

Getty Images/wrangel

Twenty-three towns claim the honor of scions of the Charter Oak. Since its demise, many seedlings grown from the collected acorns were dispersed for special celebrations. Or as in my town, East Haddam, the acorns were acquired and grown by individuals. According to the sign between the Nathan Hale Schoolhouse and the tree, William H. Scoville, a former state representative from town, brought them home to his mother in 1899, who raised one tree to sapling size and planted it in 1902.

When I teach children about nature, I always talk about oak trees and especially the Charter Oak. I ask them to make a circle to show them just how big the Charter Oak was. They are always impressed, even more so when I tell them we could all fit inside. She was estimated to be at least twenty-one feet in circumference and nearly a thousand years old.

There are only a handful of famous trees around the world: Isaac Newton’s apple, the 9/11 Survivor Tree, the Boston Liberty Tree, Daniel Boone’s Council Tree, the Charter Oak. While many no longer survive, the Charter Oak is the only one with a monument to mark its resting place. In 1905, a stone column reminiscent of a tree trunk was erected at the corner of Charter Oak Avenue and Charter Oak Place near the site where the mighty oak stood for all those centuries.

Alison C. Guinness is a resident of East Haddam, CT, where she researches the local earthquake phenomenon called the Moodus Noises. She is an historian and naturalist with interest in Portland brownstone and other quarrying in the Connecticut River Valley. She has curated exhibits at the Connecticut River Museum on brownstone, Connecticut River fish and wildlife, and boat building. She is currently studying Connecticut’s Cultural Stone Landscapes.