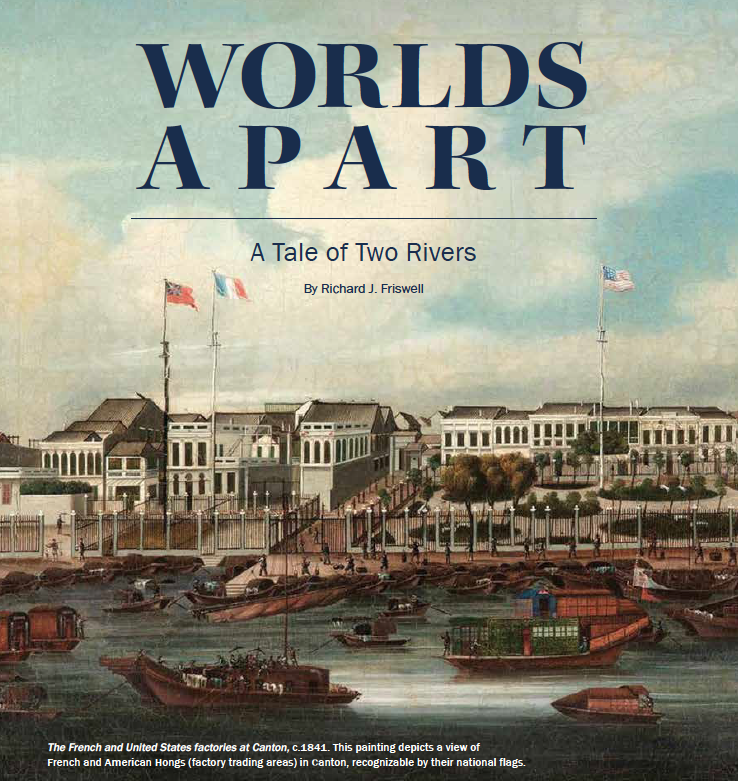

Image Credit: Australian National Maritime Museum Collection Purchased with USA Bicentennial Gift funds.

The Connecticut River cradles the city of Middletown (f. 1653) at a modest bend in its course, a place originally called Mattabesset, Algonquin for “end of the carrying place.” Tranquility now prevails over the city’s waterfront park, with its east-facing view of neighboring Portland (once called Chatham), and expansive southerly vista toward Haddam’s broad navigable channel.

The Connecticut River cradles the city of Middletown (f. 1653) at a modest bend in its course, a place originally called Mattabesset, Algonquin for “end of the carrying place.” Tranquility now prevails over the city’s waterfront park, with its east-facing view of neighboring Portland (once called Chatham), and expansive southerly vista toward Haddam’s broad navigable channel.

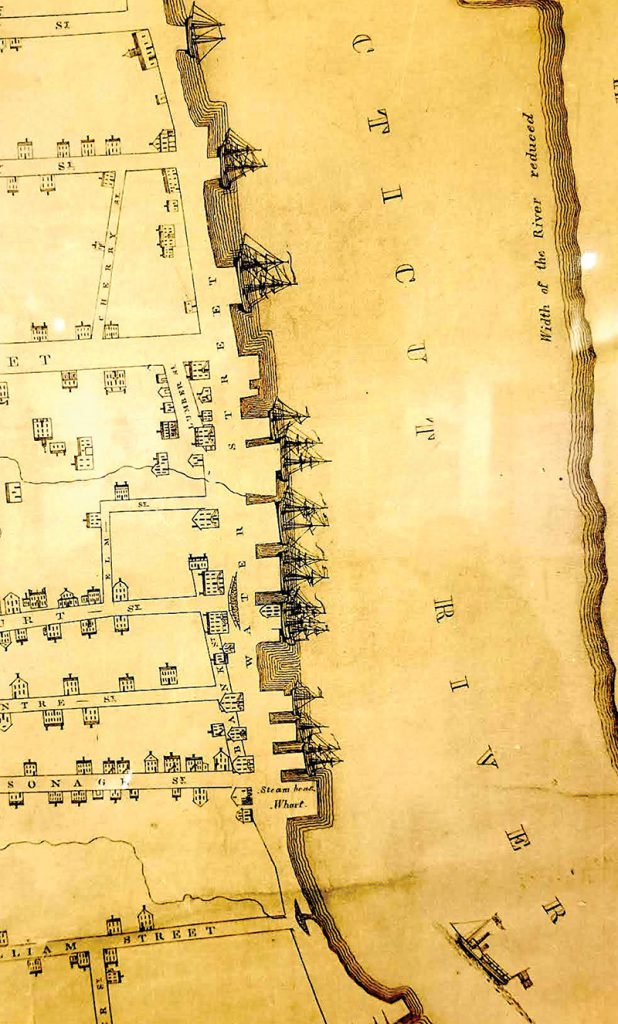

Early 19th c. print, “Bird's Eye View of Middletown Waterfront” showing extensive shipping activity. Image Credit: Russell Library Collection

But 18th and 19th century residents witnessed, instead, a bustling town whose waterfront was a busy, international shipping port, rivaling New York, Providence, and Newport. As a port, it was ideally located twenty-six miles distant from the hazard-prone Atlantic, yet central to the port’s principal function: assembling and shipping a steady flow of goods to-and-from thriving settlements in the West Indies.

The farms and fields of Central Connecticut produced so-called “country produce” for export to white-owned, island-based plantations: dried and salted meat and fish; root vegetables; cheese; butter; beans; corn; apples; barrels and lumber; and—on deck—livestock like horses, hogs, sheep and—below deck—geese and turkeys. This local produce supported burgeoning slave-based industries, turning out quantities of sugar, molasses, rum, salt, fruit, coffee, and spice for export. Those same vessels, then, returned carrying high-value, tropical goods to eager New England consumers. Slaves, supplied by the Transatlantic Triangle Trade Route, were carried home, as well. They were meant for indenture on farms and wealthy Connecticut households. A little-known fact is that in 1774, for example, Connecticut Colony had the largest population of slaves—more than 5,100—the most of any New England colony. Many were purchased at auction on the docks and streets of Middletown. Even as a 1784 act of “Gradual Abolition” forbade their sale, requiring that those subsequently born would be freed on-or-before turning twenty-five, many remained in the service of prominent Connecticut families, well into the early decades of the 19th century.

Samuel Russell was born into this flourishing setting in 1789. Purportedly the son and grandson of ship captains, Russell lived with his extended family—just blocks from the riverfront. In 1811, when he was just twelve, his father died, leaving him the oldest male and the family’s main provider. Sam quickly built an ambitious and reliable reputation with businesses on the streets and docks of Middletown and its 5,400 residents.

It was the times and unique circumstances of his coming-of-age in this maritime community, without land to farm, that eventually led him to business. The years spanning the 18th and 19th centuries marked the corresponding birth of an American nation in a new Industrial Age. Means of production rapidly moved from households to factories, labor moved from farms to cities for skilled jobs, and global demand for far-flung goods was growing. The nascent United States, emboldened by a credo of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” had the resources, national ambition, and desire to exploit the riches of European markets. Russell’s personal qualities, later documented by a peer, of “honesty, integrity, and reliability,” soon led Russell (in his twenties) to an international trading company and a European-bound trading assignment.

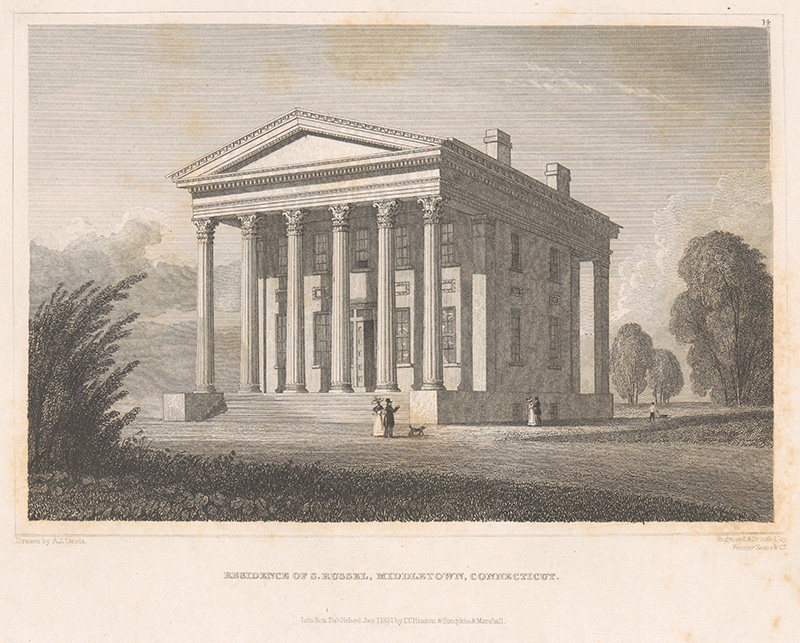

Artist unknown, Portrait of Samuel Russell, c.1850. Below: Residence of Samuel Russell, Middletown, Connecticut, 1831. Image Credit: Property Wesleyan University Collection

He was responsible for the secure handling of cargo, designated as “supercargo”—cotton goods, mostly—and its profitable sale to foreign merchants, with a safe return of proceeds to his employer (a Providence-based exporter). In 1819, after two successful European trips, his employer directed him, as an agent, to repeat the European venture, then sail directly to Canton, China, at the head of the Pearl River, using sales proceeds to establish a trading company. There he would join other Western interests, principally the English, in a location called, the Thirteen Factories. The objective: selling New England-made goods and produce to the Chinese, in exchange for tea, silks, and porcelain.

It was problematic, though, that the Chinese—long an isolated and self-sufficient nation—weren’t interested. After a concerted effort spanning several months, Russell eventually chose a more controversial, yet highly profitable route for his new entity, Russell & Co. Informing his partners in Providence of his intent to follow in the steps of the British East India Company, and their wealth-building success with local merchants and Cantonese brokers, he also turned to dealing in opium. The change in strategy was straightforward. First, sail to Turkey or India, where cotton products were in demand. Trade those for local opium and proceed to China, where there was a seemingly limitless and eager opium clientele. The proceeds in silver were then used to purchase silks, tea, and porcelain. These commodities were brought back to the US, where they were auctioned, sometimes right at dockside. With luck, this roundtrip cycle could be repeated twice a year by the same vessel.

It was a winning formula. Russell’s twelve-year residence in Canton (1819–32), resulted in the largest, most successful company of its kind. Many prominent New England men also partnered with Russell, returning home to apply their gains (“competencies”) on ambitious private and public causes. The sale of opium was not illegal then, only frowned upon, like alcohol and tobacco abuse. Derivatives of opium later appeared as morphine, indispensable during the Civil War, and Codeine, a common ingredient in cough and pain medicines. As with the Oxycontin and heroin (another opium derivative) crises of today, the issue with opioids, particularly, is not the drug’s efficacy, but how it is used or abused for profit.

Engraving and etching on wove paper. By Alexander Jackson Davis, American, (1803–1892). Image Credit: Open Access Image from the Davison Art Center, Wesleyan University, photo by T. Rodriguez.

Today, one need only walk a few blocks from the Connecticut River to the corner of Middletown’s Washington and High Streets, where stands the Samuel Russell House—a grand legacy to Russell’s ambition. He returned from China briefly in 1827–28, using a portion of his newfound wealth to construct this neoclassical masterpiece. Designed by Ithiel Town (also of Wadsworth Atheneum-design fame), it is now part of Wesleyan University and on the National Register of Historic Places. Its gleaming white façade is graced by six Corinthian columns, brought by barge from New Haven, Connecticut, where they were intended for use in a failed bank construction project.

And like so many other public and private structures scattered throughout prominent cities of the Northeast, this, too, is the house that opium built.

Richard J. Friswell, MPhil, is a Wesleyan University Visiting Scholar and director of the Wesleyan University Institute for Lifelong Learning (WILL). He is the author of three books on topics related to cultural history, including, Hudson River Chronicles: In Search of the Splendid & Sublime on America’s ‘First’ River (2019). A resident of Branford, CT, he lectures widely on topics related to the modern era, the period, 1750–1945.

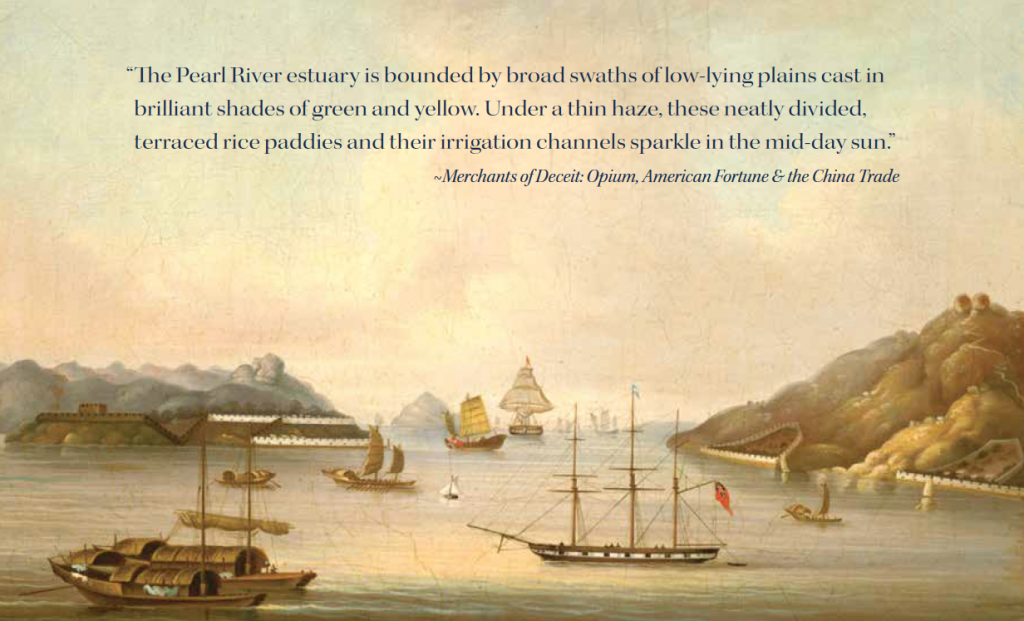

A View into the Boca Tigres (“Mouth of the Tiger”), Pearl River, China. Chinese School, 19th century. Image Credit: Collection National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.