Queen of Wall Street, Witch of Wall Street. Whichever sobriquet you use, Henrietta (Hetty) Howland Robinson Green was one of the richest Americans—ever. Hetty was known to be extremely wealthy, but also miserly, disheveled, and “salty” of speech. But Hetty was more than that. She was a financial wizard in an age when men controlled everything. She was an outlier, a woman with money-making savvy that surpassed many of her male counterparts.

Hetty Howland Robinson Green, 1835–1916, half-length portrait, seated, c. 1897. Image Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Hetty was born into a wealthy Quaker whaling and banking family in New Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1834. Isaac Howland Jr. and Company owned more ships than any other, and their banks made more money. Not surprising that the families should unite through marriage. Isaac’s partner, Edward Mott Robinson, took Isaac’s daughter, Abby Slocum Howland, as his wife.

You would think this was a match made in heaven, but Edward’s goal in life was to make money and to pass that ambition on to his son. Hetty, however, was the firstborn, and Edward rejected her for not being a son. The second child, Isaac, died after only a few months, adding to Edward’s anger and sending Hetty’s mother to bed for a good part of her life, with poor little Hetty being sent off to live with her grandfather Gideon Howland.

As Hetty grew, her aging and sometimes inebriated grandfather asked her to read him shipping news and write letters, which is where she learned how to be a businesswoman. When the old man died, her inheritance went to her mother, which meant her father, now manager of the company, invested the money and increased their wealth. All the while, Hetty watched and absorbed as she trudged the docks with her father and became more involved in the business.

In 1854, Hetty was sent to New York to become a polished young woman and find a suitable husband. Her father placed $1,200 in an account for her use while hobnobbing through high society. When she returned to New Bedford, he asked why she spent only $200 of it. She proudly announced that she had invested the rest and had done well, hoping to impress her father of her prowess with making money.

Unfortunately, Hetty’s father trusted no one other than himself with the family’s funds. When he died in 1865, he put most of Hetty’s inheritance in a trust. When her rich spinster aunt did the same thing a few months later, Hetty was very angry and began the long litigious rest of her life. The suit over her aunt Sylvia Howland’s estate became a landmark case still known today. Among those who testified for Hetty over the validity of her aunt’s signature were Louis Agassiz, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and John Quincy Adams. The case was still in litigation in 1895!

During Hetty’s stay in New York, she met Edward Henry Green, fresh from spending 20 years overseas making his fortune. Edward was ready to settle down but not to give up his penchant for high living. This high roller and stiff Quaker married in 1867. He was 47; she was 34. By this time, Hetty was a very wealthy woman.

Their honeymoon to London lasted seven years. While Edward worked to gain investments in American business and became a director of several banks, Hetty took the interest from her trust and bought government bonds and railroads. By the end of one year, she made $1.5 million. Her father told her never to borrow, and she never took risks as men in business often did.

Hetty Green’s residence, Bellows Falls, VT, circa 1900–1910. Image Credit: Detroit Publishing Company photograph collection/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs.

In between investing and raking up a fortune, Hetty gave birth to a son, Edward, called Ned, and a daughter, Sylvia. Hetty now had heirs to whom her vast fortune would go directly, not the way she had to wait for hers locked up in several trusts with various men doling out HER money while raking in large fees. This is probably where Hetty became distrustful of doctors, since one Dr. Gordon was her biggest nemesis.

In 1871, the fires in Chicago and Boston as well as runaway speculation and several financial and political scandals led to tight money which culminated in the great Panic of 1873.

Hetty and Edward headed home to check on their investments. Their first stop was New York, where Hetty visited her banker. Hetty was perhaps the first person to live by the mantra to buy low and sell high and never on margin. After the Civil War, the dollar had been discounted and Hetty bought a lot. Now, Congress, in one of its attempts to improve the economy, legislated to back the dollar with gold. By waiting, as Hetty often did, she added even more to her wealth. Seeing the depression as an opportunity, Hetty sent her banker to Wall Street to buy.

At the same time, Edward’s fortune was tanking. Hetty bailed him out, as she did on several occasions, which eventually led to their separation. In the meantime, the family went to Edward’s hometown, Bellows Falls, Vermont. When Edward’s father passed away, he purchased a house for his widowed mother Anna on Henry Street, named after the family, not far from where the whole family would eventually be laid to rest in the Immanuel Cemetery. The thought of being under the thumb of someone else did not sit well with Hetty, but Anna had paved the way for their return. The whole town knew of Edward’s exploits abroad and the gifts he’d sent his mother. When they got off the train, people were expecting a princess. (Hetty was often referred to as the Princess of Whales!) What they saw was Hetty Robinson Green, the penny-pinching, unkempt scion of a simplistic Quaker family who had grown up on the docks of New Bedford. It was the beginning of the great public misunderstanding of Hetty Green.

There were great expectations of her as a wealthy woman: to live high and spread her money around. That wasn’t who she was. She was brought up to distain the ostentatious, to keep her eye on the prize of making money, not spending it. In an age where the wealthy flaunted their riches, Hetty was an oddity. Not to mention the fact that, as a woman who made her money on her own, she was counter to the culture of the time. Those whom she felt treated her fairly received her friendship and respect.

The rumors of her miserliness were rampant, especially the ones surrounding little Ned’s leg amputation. To this day, she is known for being too cheap to take her son to the doctor. The true story is altogether different. Young Ned had a history of banging his knee. Hetty had acquired nursing skills over the years, starting with her ailing grandfather. She took care of Ned’s knee as well. When it seemed better, she told the doctor he wasn’t needed and sent him away. But the knee would not heal. Hetty and Edward took Ned to different doctors all over the country who all agreed that Ned had dislocated his knee, and it needed to be amputated, a fate Hetty refused for her son. It wasn’t until 1887 after several more injuries that Ned’s leg had to be amputated. By then, he was a young man.

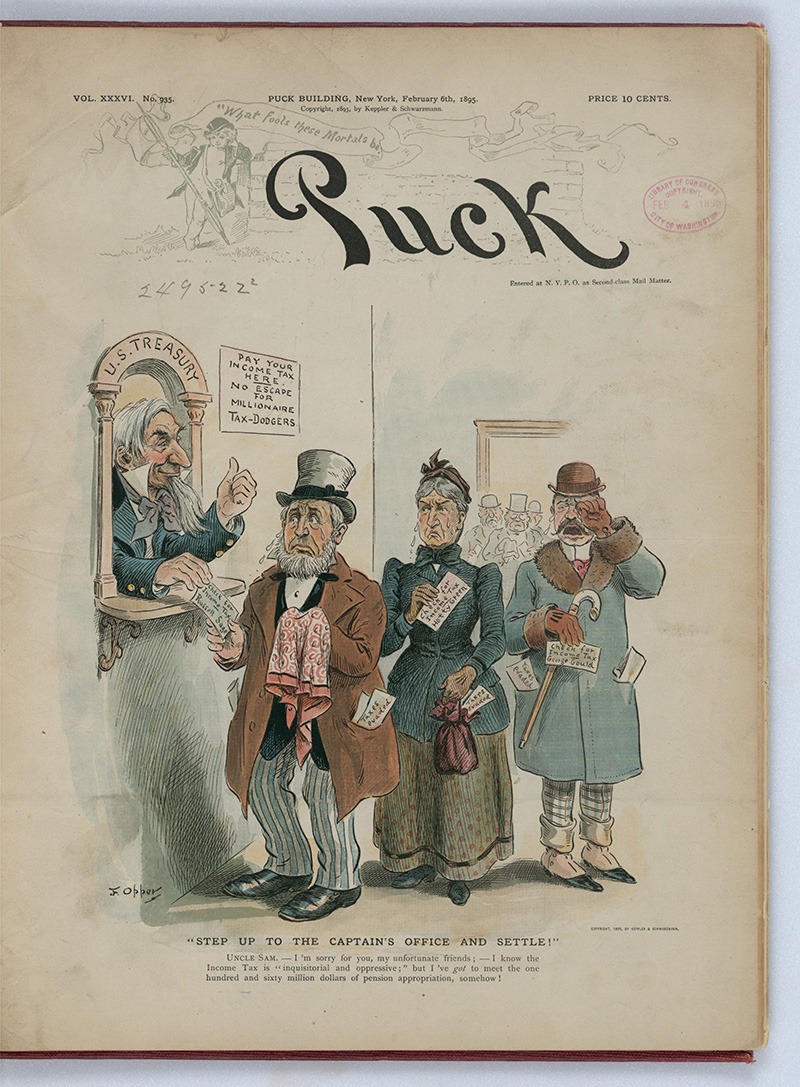

Editorial Print “Step up to the captain’s office and settle!” by F. Opper published in Puck in 1895. Print shows Uncle Sam at a cashier’s window labeled “U.S. Treasury” next to a notice that states “Pay Your Income Tax Here - No Escape for Millionaire Tax-Dodgers.” Russell Sage, Hetty Green, and George J. Gould are standing in line, looking forlorn and crying as they pass their “Check for Income Tax” to Uncle Sam. In their pockets are papers labeled “Taxes Evaded.”Despite his handicap, he traveled all over with Hetty, often in a private train probably on some of Hetty’s railroads. Hetty owned property and held mortgages everywhere, including the town of Cicero that later became the lair for Al Capone, and a large part of downtown Chicago, now the Loop. Image Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs.

Hetty was known for wearing modest, used dresses and living in boarding houses to avoid paying taxes. Despite this, she made numerous loans to the city of New York to hold off bankruptcy. She often charged interest rates below market. She also supported workers and the right to a living wage.

In 1906, another disaster, the San Francisco earthquake, started the world down the road to another major panic. This time, J.P. Morgan gathered other wealthy folks together to save the whole country from going bankrupt, including Hetty.

It’s impossible to know exactly how much money she acquired. Hetty cherished her privacy. Most of her donations were made anonymously. Consequently, estimates of her wealth are probably off by millions. She certainly deserves to be esteemed rather maligned as she was in her own time.

Alison C. Guinness is a resident of East Haddam, CT, where she researches the local earthquake phenomenon called the Moodus Noises. She is an historian and naturalist with interest in Portland brownstone and other quarrying in the Connecticut River Valley. She has curated exhibits at the Connecticut River Museum on brownstone, Connecticut River fish and wildlife, and boat building. She is currently studying Connecticut’s Cultural Stone Landscapes.