Chapter 6: Gone Shad Fishing

Why should I stop my schooling just because everybody says, “No son of a ferryman in Saybrook ever continued on to a higher school after he turned fourteen?” Boys like me are expected to go to work by age fourteen. I ask, why can’t a fellow work and go to school?

The only higher school in Saybrook is the Academy, so that’s where I’ve decided I’ll have to go. My teacher, Mrs. Gerard, said it costs one hundred dollars for one school year at the Academy, and a fellow has to be “welcomed in” to attend.

I know Cap can’t spare one hundred dollars for such high ideals because he has dedicated all the family savings toward a new ferry. But he and mum agreed I could go on with school as long as I find a way to earn the money myself and keep on doing ferry runs when Cap needs me.

“I’ll tell you how you earn that one hundred dollars, and a lot more,” Cap said. “Shad.”

“Shad?”

“Between April and June,” he said, “the shad enter the Connecticut River by the hundreds of thousands to spawn. A fellow fishing for shad in those three months can earn more than a ferryman like me can make in a whole year. You ask your uncle Henry to help you out. He and Amy make shad their summer business.”

“Why don’t we make shad fishing our summer business?” I asked.

“Because citizens of Saybrook need to cross the river,” Cap said. “Travelers and clergy need to cross. Farmers taking their goods to market and soldiers need to cross. Would my great-grandfather have left a sign for George Washington and four companies of his troops back in 1776: ‘Sorry, no ferry today. Gone shad fishing’?”

I step off Jamaica pier at Ragged Rock into Uncle Henry’s currach.

“Afternoon, Uncle,” I say.”

“Good to see you, JJ. Ready to learn a bit about fishing for shad?”

“Ready to get started on earning one hundred dollars by the end of summer, Uncle.”

He nods. “A means to an end. That’s fine.”

We row out into the choppy water of the Connecticut River. Men and boys gather in small clusters all along the river’s edge to fish in spots where the shad mill around in the warm waters of mid-May.

“Is it better fishing out on the river than from the piers and riverbank?”

“Those fellows will be catching twice as many shad from the shore as we will out here on the river, but our goal this afternoon is to take it easy and learn a little about shad. Tomorrow, we’ll wait until nightfall and go to Folly Point, near the lighthouse, and work off the beach with a seine net crew. You’ll catch plenty, then.”

Uncle Henry dropped the anchor in a spot with no other boats nearby. He reached into his pocket and took out two hand-carved wood darts with horsehair tails, “Squire makes ’em,” he said.

I felt around and looked under my seat. “Where’s the bait can?”

“No need for bait, JJ. Shad don’t eat when they’re spawning.”

We each tie a dart to our lines and cast off—me off the bow; Henry off the starboard side. “Cast shallow, JJ, reel in slow, and then cast again and again until you feel a tap. It won’t take but a minute or two.

“So, JJ. You say you went to the Academy to apply?” Uncle said, reeling in his dart and casting again.

“Well Uncle, instead of a slate, the reverend handed me a little booklet with ruled pages, a quill pen, and said: ‘Write why you think I should let you attend classes here at the Academy when no son of a ferryman ever went to school here. Write there,’ he said, pointing to the booklet, ‘why you think you’re different from all the others.’”

“Put you to a task right away, did he?”

“Tell you the truth, Uncle, I think he figured he might scare me away.”

“Maybe thought he’d end it right there, thinking you couldn’t spell or write, or express your thoughts,” he said.

“Reverend said he’d mark up what I wrote and that I could get my booklet back by today. I asked Clara to pick it up for me.”

I felt a hard tug on my line, so hard my pole almost jerked out of my hands. “I got a tap...” I jump up and then shout out, “There’s another one!”

I lift my rod and set my feet wide for balance. My line dips and swerves. My rod starts to bend toward the water with the third tap so I reel in as fast as I can. I lean back and try to raise my pole, my right-hand spinning in circles, trying to reel in my catch.

Seagulls and terns appear out of nowhere. White wings and black caps flash as they swoop and dive at the churning water around my catch, while just under the surface of the water a swarm of schooling shad pass by. The birds are diving for the baitfish leaping out of the water, bright orange beaks wide open yelling at each other like kids running to catch a single ball, shouting: Mine! Out of my way! Hey! You cut me off!

“It’s a roe shad,” Uncle says, as she arcs out of the water. “She’ll be worth a lot, JJ. Especially if she’s boned. We’ll see if my Amy’s hands are limber enough today to bone it for you. You’ll need the likes of Amy if you want get the top dollar for your catch. A single shad can have up to 1,000 bones—how a woman gets those bones out, that’s their secret. Fishery pays top dollar for boned filets.”

“Look at her go, Uncle. Are you sure I’m not going to lose her?”

“No way to be sure, JJ. But looks like you’ve got a pretty good hold.”

“Wouldn’t I make more money if I bone the filets myself?”

He laughed. “Boning is strictly a woman’s job, JJ. But it’s crippling work. I’ll not have my Clara learning it either. I see better futures for Clara and the twins.

“Let out some line, JJ. Don’t crowd her.”

As soon I give her some slack that lady fish dives down deep. “I’m going to lose her uncle, if she keeps this up.”

Next thing I know that shad shoots up and out of the water, headfirst, and stands on her tail. I could see my line going into her mouth. “Look, uncle. She’s walking on her tail.”

He laughs out loud. “It’s the bucks that usually show off like that, lots of acrobatics. You got a roe shad tail-walking, showing those bucks how it’s done. Give her some more line.”

“What? Why? She’ll drag us all the way upriver to Essex.”

“She’s a prize, JJ, maybe six pounds. She’s challenging you, behaving like she knows her worth. Give her a chance to make you work to catch her.”

“But, Uncle, I already caught her. All I have to do is reel her in.”

“Not yet. She’s taking you to school, JJ. Pay attention to where she goes and where she doesn’t go. Does she head toward the rocks? Dive deep into the current? If she’s looking for warm water, she’ll stay close to the surface. Shad aren’t loners, they spend their life in a school, does she try to join a school that’s passing by to confuse you? Remember, there are a hundred thousand shad out there with her, all headed upriver, all with only one thing in mind, and that’s spawning.”

When Uncle Henry finally said it was time to reel her in, I scooped her up in my net but fast, removed the dart, hooked my finger in her mouth, and lifted her up high to show off to Uncle and any fellows along the bank that might look my way.

“Magnificent,” Uncle said. “Now, put her into the bucket of water. Remember to save a few of her scales for your record book. I’ll teach you how to read the rings of her scales—like reading the rings of a tree—those rings will tell you where she came from, how old she is, how many summers she has returned to this spot to spawn. You can read her life in one scale.”

“How much money do you think I’ll get for her?”

“Top price at the fishery. Fifty-five to sixty-five cents, if I was to judge just by her weight. Could be well over one dollar if Amy agrees to bone the filets for you.”

“How much do I pay auntie?”

“That’s between the two of you, JJ.”

Uncle Henry took out his pocket watch, flipped it open, and said, “Sun’s almost down. Let’s row ourselves upriver, I know a spot where the shad bag up, at the bottom of a little rapid. Let’s see how many we can catch in the next thirty minutes; you’ve got to have more than one roe for your first catch.”

I got thirty-five cents each for the two bucks I caught near the rapids, and a whole dollar for the boned and filleted roe. Auntie didn’t charge me anything to bone my roe shad. A dollar seventy for one afternoon of shad fishing. Just $98.30 to go.

Clara gave me the marked-up blue booklet at the planked-shad supper tonight. The reverend wrote inside the front cover: A fair bit of writing for the likes of a ferryman’s son. He didn’t say he’d “welcome me” into the Academy; he didn’t say he wouldn’t, either.

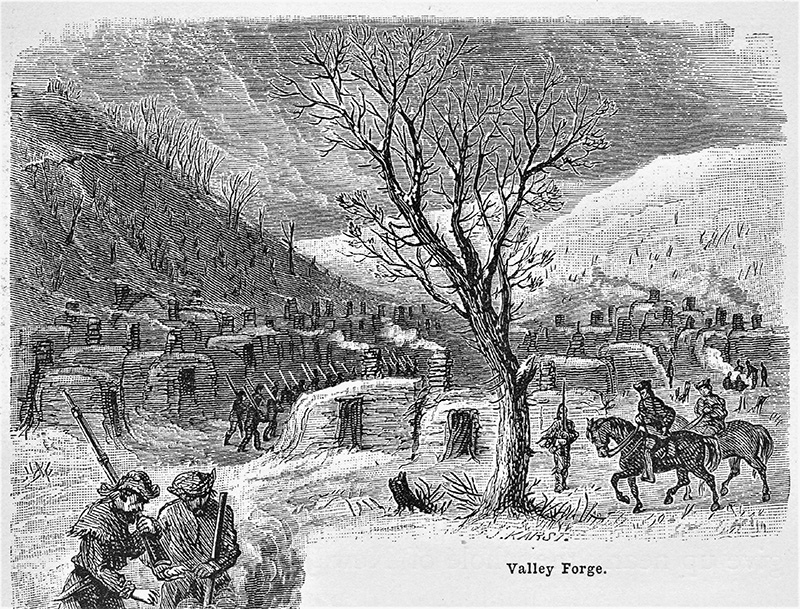

In December of 1777, George Washington and 11,000 troops made their encampment in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, alongside the Schuylkill River. The winter of 1777–78 was harsh, and Washington didn’t have enough food to feed his troops. A sudden warming of the river water caused the shad to begin their spawning run early. Hundreds of thousands of fish appeared in the river, enough fish to feed an army.

Cavalrymen rode their horses into the river and thrashed at the water with sticks and branches, like herding cattle or sheep, driving the shad by the thousands into the waiting nets that spanned the river from bank to bank, held by troops on each side. In this manner the troops were able to capture shad by the thousands, enough to save the encampment from starvation through the winter and into the spring of 1778. Thousands more of the shad were caught, salted, and stored in barrels for the remains of Washington’s march to Virginia to fight the battle of Yorktown, in October of 1781.

During Colonial times, shad provided food when none other was available, to the extent that the shad is often called the “Founding Fish.”

Centuries before the Europeans arrived in New England, Native American tribes had developed their own methods for catching and preserving shad.

The shad is the state fish of Connecticut.