Image Credit: Getty Images/Vectorpower (trees illustration).

New England’s First State Forest

It’s Not Just About Trees

From the rocky knob of Great Hill at the southern tip of Meshomasic State Forest, I gazed at a big bend the Connecticut River takes in the middle distance, with ridges fading to gray-blue behind it. Looking out from among stunted oaks and gnarly pitch pines, I saw smokestacks from Pratt & Whitney’s Middletown plant. In the foreground, 76-acre Great Hill Pond mirrored the sky. Houses were set among trees. It’s quintessential semi-rural Connecticut. Yet, to my back, was roughly 9,000 acres of rugged state forest, rich in history, surprisingly wild.

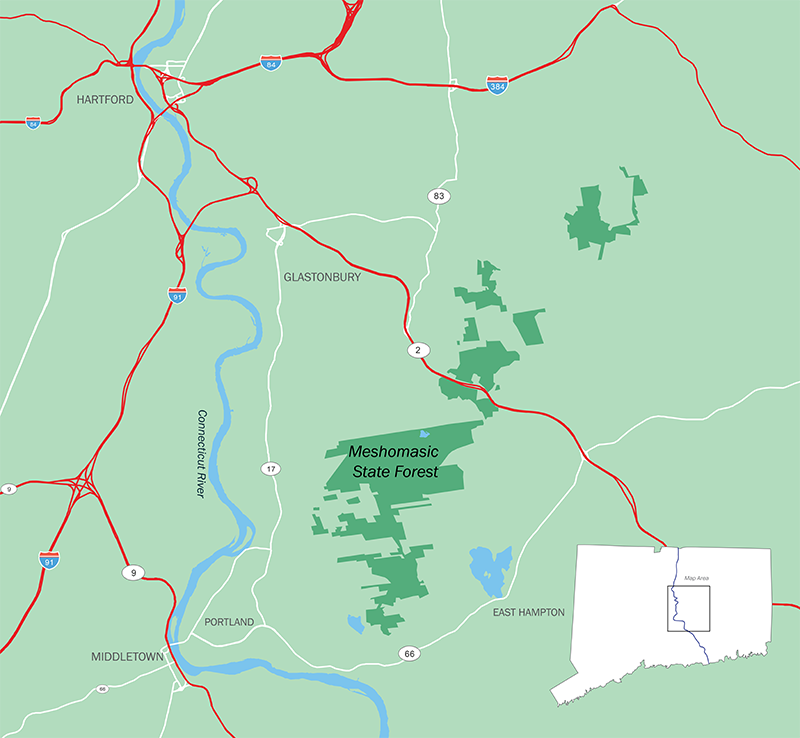

Situated about midway between New York and Boston in the Connecticut towns of Portland, East Hampton, Marlborough, and Glastonbury, Meshomasic was established in 1903, New England’s first state forest and just the nation’s second. Like many public forests, Meshomasic produces timber and provides habitat for a wide range of wildlife, including the rare timber rattlesnake, which is officially listed as endangered in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont. It offers hiking, mountain biking, cross-country skiing, hunting and wildlife watching. Audubon Connecticut considers Meshomasic an Important Bird Area (IBA) for the critical habitat it provides many species.

The forest has a storied history. There are the usual farm stone walls and old cellar holes, but also several mines dating from the late seventeenth to the mid-twentieth centuries. Two Depression era Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps called the forest home, and ruins of Nike missile sites from the Cold War persist among the trees. Bridging nature and culture is a breathtaking tree plantation known as the Big Pines, more than a century old.

John LeShane, Firetower Hill

On a hot, humid July day, I hiked a few miles to the summit of Pine Hill, also known as Firetower Hill, with John LeShane. In 1989, he founded the Meshomasic Hiking Club which has raised tens of thousands of dollars for land conservation. On a series of old roads and trails, most of which were unmarked, the six-foot-three Leshane led me through the woods by long strides. He grew up nearby and has adventured in the forest for about 60 years. He knows every glacial boulder, ledge outcrop, vernal pool, large tree, cave, and cellar hole, and the stories that go with them.

As we ascended an old colonial road—a wide, rock-studded path that had once been an artery of travel—he gave me a primer on the origin of the forest’s name. At first called Portland State Forest for its location, the name Meshomasic was adopted when land purchases extended to other towns. The first pieces were acquired near Meshomasic Mountain, hence the moniker. Some believe “Meshomasic” derives from an Algonquin word meaning “great rattlesnake” or “place of many snakes.” Another theory holds that the name means something to the effect of “great going down,” in recognition of the area’s rugged ledges and hills. LeShane reveled in the lack of a pat answer, that there were multiple stories.

At over 900 feet above sea level, Pine Hill is among the forest’s highest points. Despite that distinction, there is no view. It’s a grassy knoll surrounded by oak, hickory, and white pine where the ground falls away quickly on all sides. Concrete footings with rusted fittings mark where decades ago a fire tower stood. Back in 1903, when the state made its first 70-acre purchase for $105 just downslope of this spot, the view likely took in nearby ridges and valleys since the area was largely scraggly brushland, cut repeatedly over decades for industrial charcoal and fuelwood. Wildfires were common.

Walter Mulford, the first state forester, wanted to demonstrate how to grow timber, especially chestnut, and control fires. Built after his tenure, the tower was just one in a network throughout the state, a system that grew obsolete with aircraft surveillance and other means of detection. The land is now reforested with mixed hardwoods and pockets of pine and hemlock. The chestnuts prized by Mulford, once about 30% of the forest, were wiped out beginning in 1910 by a fungus accidentally introduced from east Asia. Lauded for beauty and rot resistance, chestnut has been called the “perfect tree.” Used for everything from utility poles to railroad ties, structural lumber to furniture, it also provided nuts for people and wildlife. Today, chestnut has been reduced to little more than a shrub with multiple stems sprouting from rotting stumps of once forest giants. LeShane and I passed many of these clustered miniatures with their distinctively narrow, coarsely toothed leaves.

“Scientists are trying to beat the fungus,” he said. “As long as these trees keep sprouting, there’s hope.”

Descending Pine Hill, we also encountered stands of witch hazel, a small tree used to make the familiar astringent skin care product. Traditionally harvested in Meshomasic, over 90% of the world’s witch hazel is produced by nearby American Distilling, Inc. in East Hampton.

Meshomasic is easily accessed by unpaved, seasonal roads that run through the forest. They offer beautiful drives among birch, oak, pine, and other trees, past glacial boulders and ledges tattooed with lichens. But only afoot can one experience all the forest has to offer—birdsong, wildflowers, the sound and feel of small streams tumbling over rocks, and wildlife from porcupines to bears. Laced with old logging and fire roads, colonial cart paths and trails of all sorts, there are plenty of places to hike. But unless accompanied by an experienced companion, it’s best to stick to the blue-blazed Shenipsit Trail, maintained by Connecticut Forest & Park Association volunteers.

View From Great Hill

Starting at Great Hill, the first 16 miles of this 50-mile trail traverses the length of Meshomasic from south to north. It winds through moist woodlands thick with beech and maple, follows ridges that sport chestnut oak, and skirts swamps where frogs fill the air with otherworldly calls in spring. Along the way, hikers find dramatic cliffs, boulder fields left by glacial ice, large old trees with muscular limbs, and a waterfall called The Cascade that slides down a steep rock face, splashing into a crystal pool. Occasionally there’s a view of forested ridges, and careful observation reveals ancient cellar holes, small CCC-built fire ponds, and stone walls hidden by vegetation.

Near the corner of Del Reeves and North Mulford Roads, the Big Pines are easily reached by car. Seeing them through a windshield is little better than looking at a photograph, but being among them is breathtaking.

The Big Pines are LeShane’s favorite spot in the forest. We entered the grove on a cool day with fast moving clouds that strobed the trees in bright light and shadow. There’s brush in the understory, the ground is soft with needles, and the trunks stand out like columns on some grand, classically designed public building. When the sun is out, angled shafts of light fill the space between them. I strained my neck looking up into the bluish-green crowns, each with a distinctive shape.

We walked slowly, almost reverentially, as if within an outdoor cathedral. LeShane spoke softly as he detailed the history of the trees, planted during a cold April in 1908 with seedlings from Biltmore in North Carolina. He approached several of the giants, seemingly greeting them like old friends. Soon we reached the largest tree, by LeShane’s estimate 130 feet tall and about 11 feet in circumference. I felt as if I was being introduced to royalty.

“These are our redwoods,” he said. He’d seen them scores of times, but still his voice trembled with awe.

Mining began in what is now Meshomasic in the late seventeenth century with Governor John Winthrop’s search for gold at the base of Great Hill. He’s said to have spent weeks in the woods roasting ores and assaying metals, finding at least enough gold for a ring or two. Other spots have been worked for cobalt (used for the decorative blue color on china), nickel, feldspar, and mica. None were ever very successful.

The Cascade

Along Mine Brook south of Gadpouch Road on another day, I wandered on uneven ground in woods of oak, beech, and black birch with geologist and mineral enthusiast Harold “Fritz” Moritz. He showed me a series of trenches where gold digging attempts had been made in the nineteenth century. Standing by the brook, he pointed out veins of quartz washed clean by the water to reveal streaks of a mineral associated with gold. In the 1980s, he said, a University of Connecticut professor confirmed traces of the precious metal.

Brimming with information that ranged from the working conditions of nineteenth century miners to use of beryl in nuclear weapon triggers, Moritz is an athletic man with steely close-cropped hair and clear blue eyes. He moved quickly and with enthusiasm. I followed him downstream along the brook, past vertical shafts and horizontal tunnels that were remnants of cobalt and nickel mining. Tailing piles and remains of a stone structure were hidden by vegetation. Imagining mining at its height, Moritz described a landscape of few trees. It was a place busy with men and horses, and studded with storage sheds, black powder magazines, blacksmiths, and stables—a noisy, smoky place. I found it hard to contemplate in the thick woods where all I heard was running water and birdsong.

Heading even further downstream, we came to State Forest Quarry #2, an excavation in the side of a ledge where mica was briefly mined during World War II. Among other uses, mica found its way into vacuum tubes essential for radio communication. A small pile of fragments sparkled, even in the shade.

Just off Woodchopper’s Road and along the Shenipsit Trail, is State Forest Quarry #1, where a steep ledge has been chipped away leaving shallow hollows. Feldspar (used for ceramic glaze) and mica were sought here for a few months in 1942 and 1943. Nearby, is Nathan Hall Quarry, abandoned in the 1920s and largely hidden in the woods. Rockhounds are drawn to both sites (with a state permit) to search the waste piles for beryl, garnets, muscovite (mica), and other prized deposits. As we wandered among the discards, Moritz picked up chunks to show me embedded minerals.

A short ride away, we hiked uphill under crackling powerlines crossing Cotton Hill Road to a series of four excavations on high ground called Case Quarries. Like the other sites, feldspar and mica were the commercial products mined here, and collectors (with permits) search for a similar array of minerals. A field trip with a group like the Lapidary and Mineral Society of Central Connecticut, Moritz said, is the best way for the uninitiated to explore the quarries.

Thoughts about Meshomasic naturally run to what is on or in the land, but between 1956 and 1963, during the Cold War, a dedicated group of men focused on the sky. Hidden in the forest was one of the nation’s over 150 Nike Missile batteries ready to launch 40-foot-long rockets with nuclear warheads against Soviet bombers.

The control site was on high ground above Del Reeves Road, and contained radar installations, guard stations, and barracks. The launch site was off North Mulford Road. It also included guard stations and barracks but had the missile batteries and a medical office. Today, driveways of broken asphalt lead to each. All that remains of the control site are foundations, overgrown paved paths, construction debris, a steel water tank painted with colorful graffiti, and stairways that lead nowhere. The launch site magazines are largely filled with sand and soil, but some openings remain with vent fans or metal ladders that go nowhere. Before they were filled, LeShane remembers wandering in a vast concrete cavern. Now, as ruins, the sites are eerie, slowly being overtaken by the forest, a reminder of how close we once were to nuclear disaster, and a cautionary tale of how quickly “space age” technology grows obsolete.

The Civilian Conservation Corps also lasted less than a decade, but unlike Nike, its impact is still felt, largely in about eight miles of unpaved roads. Marty Podskoch sees CCC ghosts. A soft-spoken retired teacher, he lives just a few miles from the forest and wrote a book on Connecticut CCC camps that’s rich in detail and filled with memories of the young men who lived and worked at them.

Last Remains of Camp Jenkins

On a cold spring day, we walked an abandoned driveway off Gadpouch Road at the foot of Great Hill. We came to a large open field of encroaching vegetation, but Podskoch described a parade ground, barracks, recreation hall, and other buildings. It’s the site of Camp Jenkins, established in 1933 shortly after President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the CCC-authorizing legislation into law during his first 100 days in office. The “boys” built truck and fire roads, trails, bridges, and picnic areas. They played sports and even had a camp newspaper. We couldn’t see a single structure, but it all came alive for me as Podskoch spoke with so much loving detail, I imagined he’d been there. Searching among tangled brush and vines at the field’s edge, we at last found a fieldstone chimney hidden in the vegetation like some pre-Columbian ruin in a Central American jungle. It was the last surviving evidence of what was once a busy place, an informal memorial to those who had served.

Camp Jenkins closed in 1936, but Camp Buck operated on high ground off Great Hill Road several miles away between 1935 and 1941. Unlike Camp Jenkins, the site is still clustered with buildings and remains a hive of activity as the Portland Depot of the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP). Functions include the state’s only sawmill, first established here by the CCC. Camp Buck projects included thinning stands of pine and larch, surveying tree diseases, and controlling gypsy moths, as well as road building and other activities first performed by crews at Camp Jenkins. In addition to the CCC sawmill, Podskoch described a creosote plant operated to preserve guardrails and fenceposts, and a brick charcoal kiln, both long gone. Like Camp Jenkins, there was a newspaper and organized sports. Guest speakers came, academic courses were offered, and there were agricultural and handicraft clubs. “It was a real community,” Podskoch said.

Not long after my CCC tour, I met with DEEP forester Nathan Piche at the Portland Depot, in a pole barn stacked full of fresh sawn lumber. He’s an engaging, rangy fellow, a 2015 graduate of Paul Smith’s College. It’s his job to develop and implement management plans that balance timber harvesting, wildlife diversity, landscape conservation, and recreation, a responsibility he takes earnestly. One of the biggest immediate problems the forest faces, he observed, is illegal ATV use which rips up trails, compacts soils, and causes erosion. My wanderings in Meshomasic confirmed his assessment. But, enforcement in remote areas remains difficult. Other longer-term threats include invasive species and climate change.

The forest produces firewood and sawtimber. A permit is issued to harvest mountain laurel for Christmas wreaths, and another for about 500 taps to make maple syrup. The sawmill now produces about 13,000 board feet a month, mostly oak and pine lumber, but the logs come from several state forests. Most of the wood goes into DEEP structures and picnic tables.

DEEP Sawmill

More than half of Meshomasic is not subject to active management because it’s inaccessible, inoperable for harvesting equipment, designated natural area, or set aside for ecological reasons. The rest is subject to active management for forest products, and just over 700 acres have been harvested for timber over the past decade.

Piche took me to a 125-acre thinning at the end of Mott Hill Road in East Hampton. There were a few pieces of heavy equipment near the landing, and a few stacks of logs ready for transport. The site was a bit muddy, so gravel and small logs had been laid on the ground to minimize impacts from machinery. Pockets of slash cut from treetops were scattered about. Not all trees were being removed, just some of the larger ones to let in light and promote growth of small and medium sized oaks. Once the loggers are gone, you’d be surprised how quickly the land heals, he said. The regenerating vegetation creates habitat for deer, many bird species, mice, and other animals.

The forest is dynamic. It’s always changing. I doubt if Walter Mulford would recognize the mature woods growing on that first 627 acres of brushland he purchased so hopefully in 1903. More than a century of stewardship has healed the landscape, even as it provides forest products, offers recreation and respite, clean air, and water. There’s a lot happening among the trees. A good pair of hiking boots and an adventurous spirit is all that’s needed to begin exploring.