Maple syrup is made according to Nature's timetable, often well into the night. Image Credit: John Buck.

Maple Sugaring

The maple sugaring season is one of the most celebrated and ephemeral of spring events to occur up and down the Connecticut River watershed. Outside the sugarhouse, the northwest breeze makes the temperature of 28 degrees feel more like January than the middle of March. But inside, the heat from the boiling maple sap has Don Malenfant and James Buck dressed otherwise. As the billowing steam from the evaporator obscures all but everyone’s feet, Malenfant reads the digital syrup thermometer; “217.6,” he calls out. Because maple syrup generally boils at 7 degrees greater than water, syrup would be ready at 219°F. But with the high-pressure weather system affecting the evaporation rate, 219 degrees might be too hot and could make the syrup too dense to be classified as Grade A syrup. Buck studies the apron-shaped sheeting of the maple syrup as it streams from his box-shaped ladle back into the boiling syrup pan.

“I think we have syrup now. Let’s check the temperature against density with the hydrometer,” says Buck. “I can’t believe we have syrup so soon. It must be this northern front of cold, dry air. Thank you, Canada!” The watched pot never boils, as they say. But when the maple pot does boil, it requires quick and precise teamwork among sugarmakers of every stripe.

Maple syrup production has a long and storied presence in the Connecticut River watershed. From the time of the nations of First People thousands of years ago, to the early European settlers of the 17th century and their modern-day descendants, maple sugar, maple syrup, and the sugar maple (Acer saccharum) have stood as a livelihood and cultural bedrock.

Algonquin, Abenaki, Passamaquoddy, and other First People tribes of what is now New England and eastern Canada all have their own history of maple sugar making and their rich culture-specific rituals that accompany it. But all had in common the life sustaining rescue brought forth by the maple trees. Far from being a garnish or treat, maple sugar was a dietary necessity of their subsistence life. Sugaring season as we know it today, was also a time of celebration and thanksgiving for having survived the unforgiving winter and for the promise of the coming growing season. Early Europeans learned the value of maple sugar and how to procure it from the First People. Having brought drills, buckets, and boiling pots from their homeland, Europeans advanced the production efficiencies and continued to make maple sugar as a staple of their subsistence lifestyle.

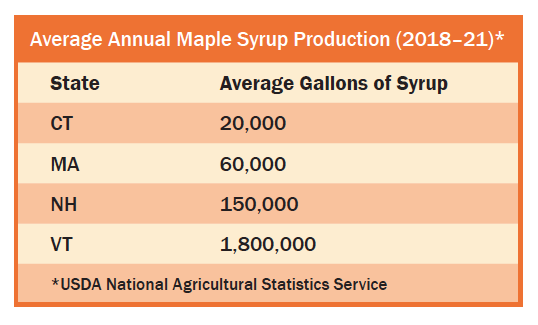

Skip ahead 250 years from subsistence use to the current worldwide demand for maple syrup and maple sugar. Today its use ranges from a sweet topping treat to a natural and sustainable dietary sugar incorporated into a wide variety of foods. That demand drives innovation and technology as well as land values and workers. Today the four Connecticut River states produce nearly 50 percent (about 2 million gallons) of US maple syrup per year. That is a value of approximately 65 million dollars (see table).

The significance of these figures is two-fold. First, sugar maples prefer to grow mainly in New England, New York, and Eastern Canada (principally Quebec). Second, syrup is produced largely by small family-operated farms ranging from a few hundred taps to a few thousand.

Howard Boyden is nearing retirement from his full-time job and has been producing maple syrup his entire life. His 3,000-tap operation at the headwaters of the Mill River in Conway, Massachusetts, has been in his family since his great-grandparents began farming it in 1760. The farm has been producing maple syrup for the last 200 years. “One of my greatest joys is seeing the grandchildren of people who regularly visited the Boyden farm when they were children,” says Howard. Family history runs deep among maple farmers: Boyden is now teaching his 3-year-old granddaughter the art and science of maple sugarmaking.

Top: Maple sap flowing through the pipeline system.

Bottom: James Buck and his father posing in their sugarwoods.

Farther upstream at the headwaters of the First Branch of the White River in Washington, Vermont, is sixth generation Vermonter and sugarmaker James Buck (also the author’s son). He started as a child in his backyard with 25 taps and a roasting pan. Today he runs the family’s 2,000-tap operation on forestland that has been producing maple syrup for over 100 years.

Both Boyden and Buck will be the first to say that maple syrup production is an excellent example of sustainable agriculture and forest management. “If each generation takes good care of the forest, the forest will take care of each generation,” says Buck. “That means taking care of not just the trees but also the soil, the water, and the plants and animals that are a part of the total forest picture. Healthy maple trees from healthy forests will produce high quality syrup for decades and centuries to come.”

Long before syrup is made in the sugarhouse, the increasing solar intensity of late winter triggers the maple trees to call upon their food reserves. These reserves of sugars, starches, and minerals were produced the previous summer and sent to the roots for winter storage. This food then nourishes the buds that will open to become the tree’s new growth of limbs and leaves.

To capture a very small portion of that food, a small hole (3/16 or 5/16 inches in diameter) is drilled into the tree no deeper than 1½ inches. A spout corresponding to its respective hole size is then “tapped” into the tree. A bucket is hung from spout, or it is connected to a pipeline system. Depending on how many spouts each maple farm uses, the tapping process can take an afternoon or several weeks to complete. Tapping happens between January and February, but all sugarmakers strive to get this phase completed before the first sap run of the season. Once in place, taps need to be checked regularly. Leaks can develop between the spout and tree or anywhere along the pipeline system. Wind, fallen trees, and rodents can compromise anyone’s collection system. Any sap loss due to equipment damage or failure is a loss of syrup for the year. It cannot be recovered in the short 6–8-week season.

Helping hands among the maple-infused steam inside the sugarhouse.

Daytime temperatures in the 40s and overnight temperatures just below freezing are best to produce good sap runs. This doesn’t happen with any regularity, so there are many days when little to no sap flows. But, on those good days, it is not uncommon to receive as much as 2 gallons of sap per tap. The collected sap then has to be gathered and brought to the sugarhouse. Topography, distance to the sugarhouse, and the number of spouts determine how best to accomplish this. Carrying buckets on foot to a gathering tank is a common practice among smaller operators. However, a gallon of sap being mostly water weighs approximately 8 pounds. Therefore a 200-gallon collection tank could weigh as much as 1,600 pounds. That is something to consider whether collecting from several hundred taps or tens of thousands. Pulling a tank-mounted sleigh or wagon through the woods’ roads with a tractor or horse is one means of solving the time and hard labor question. Modern pipeline systems offer further time and energy savings

Over the millennia of maple syrup making, whether by Algonquins or European descendants, there is one fundamental fact that all cultures and generations have confronted. Water from raw maple sap that is on average 2% sugar must be removed until there is a syrupy solution between 66% and 67% sugar. Many producers use reverse osmosis technology as an initial process to remove water from sap. But even when concentrated to a 15–20% sugar solution, much of the water still needs to be removed, and that is through the tried-and-true process of evaporating the excess water through boiling. Smaller to medium sized operations use wood as a preferred fuel. Those handling tens of thousands of spouts are most often using oil or propane. Wood pellets, electricity, and steam are newer technologies that are becoming more common.

Don Malenfant, left, and James Buck monitoring the syrup temperature and density.

Evaporator features have evolved over the last 100 years, but all aim to concentrate the greatest amount of heat on the greatest amount of surface area. Evaporators typically have two sections. The front, or syrup pan, occupies about one third of the length of the evaporator. The back pan, or flu pan, takes up the remaining two-thirds. Regardless of fuel type, a constant heat travels by convection from its source under the syrup pan while being “arched” up into flu pan then out to the flu stack.

Instead of cold sap replacing the hot evaporator sap causing loss of boil, modern evaporators are equipped with preheaters and float valves that allow for a steady influx of hot sap into the boil. This continuous feed creates the temperature/density gradient that allows sap to flow through the evaporator.

To further reduce potential mixing of near-syrup with sap, both pans have a series of channels separated by short walls that resemble a maze and facilitate the gradient flow from back to front. In the front pan the sugars have now concentrated to 67% and reached a boiling temperature of 219 degrees Fahrenheit. As fresh syrup is “drawn off” (removed) from the evaporator it must first be filtered before entering its storage container. The syrup is pressed through a vacuum-activated filter or a gravity-fed cone-shaped filter.

Early spring sun warming the sugarwoods.

Pure Grade A maple syrup must meet industry standards of clarity, color, density, and flavor. The hydrometer has already accurately measured density at draw-off. The first filtered drops of syrup are fed into a glass sample bottle so its purity, color, and flavor can be assessed. Color is determined by a spectrometer or visual comparison against universal color standards, and clarity is also assessed visually. Flavor is a bit more subjective but perhaps the most important quality. If the syrup doesn’t taste like maple, it cannot pass muster regardless of its other qualities.

Now for the moment of truth. All eyes are on Don Malenfant as he holds the sample cup first to his nose then to his lips. Slowly, he takes a sip of the hot syrup. No one moves as he rolls it around in his mouth and cocks his head. Malenfant’s highly developed syrup palate would place him as a New York Times critic (if one existed). Everyone in the sugarhouse remains frozen with anticipation. Slowly, he begins to nod. Still, no one breathes. Then his grin blossoms into great big smile. “Boys and girls,” he exclaims with excitement, “this syrup is some of the best I’ve tasted in a very long time!” Everyone simultaneously exhales and spontaneously bursts into a big round of applause. “A perfect start to the sugaring season!”

John Buck is a retired wildlife biologist and co-founder of Buck Family Maple Farm in Washington, VT. He has made maple syrup since boyhood and then extended his knowledge and passion on to his family. He currently operates the family’s 70-acre maple farm with his son and co-founder, James, and the rest of the Buck family.

Syrup samples decorating the sugarhouse.