Chapter 5: Just Passing Through

Rules are rules—you have to graduate when you’re 14 years old here in the Saybrook Ferry District School. I’m not a bit happy about that, mind you, because I still don’t know what I want to do with my life. But like I said, rules are rules.

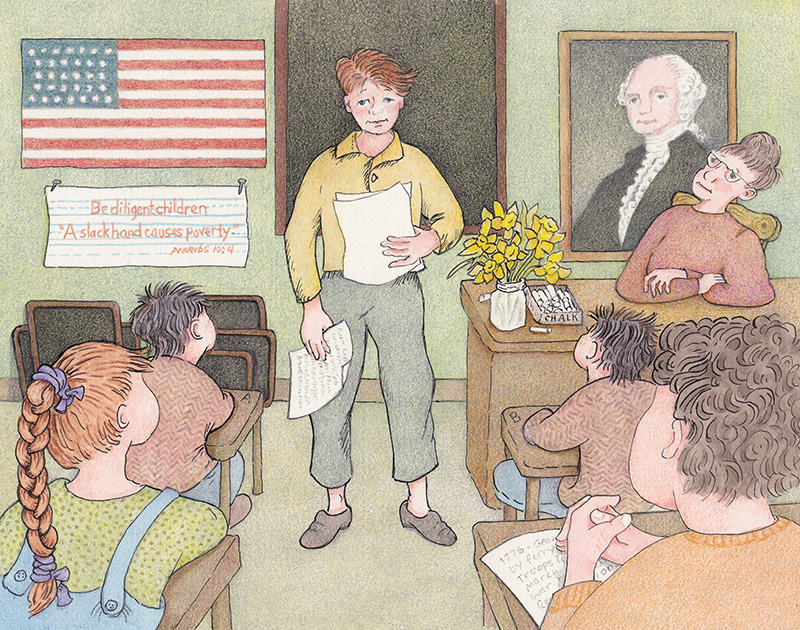

We always do ferry history on the last day of the school year, and since I’m the only graduate out of our class of 5, Mrs. Gerard, our teacher, gave me the assignment to write a report from history about the Saybrook Ferries and read it to the class. Even while she was still talking, I knew what I wanted to write about.

![]() Finally, came the last day of the school year and time for me to read my report to Mrs. Gerard and the class. But first she asked her usual history questions.

Finally, came the last day of the school year and time for me to read my report to Mrs. Gerard and the class. But first she asked her usual history questions.

“Who can cite for me an important person and date in Saybrook history related to our ferries?”

“I know,” little Ben said, jumping up from his desk, “General George Washington, it was April 9th—1776—he crossed from Lyme to here in Saybrook on a ferry. I know because you tell us every year, like you think we might not remember.”

“General Lafayette?” Clara said, lifting her hand no higher than her ear, “I’m pretty sure he came from…France? He crossed on one of our ferries to Saybrook so he could help fight in the…Revolutionary war?”

“Exceptional, Clara,” Mrs. Gerard said.

“Thank you, Mrs. Gerard,” Clara said, with a courtesy in her voice.

“Anyone else?”

Ray stood up and read from his notes. “In September 1776, George Washington came back to Lyme with four companies of his soldiers on the March to New York. All the ferries were busy that day, getting those soldiers across the river to Saybrook, so they could march to Virginia. In Virginia, Washington fought the battle of Yorktown, which ended the Revolutionary war, which may never have turned out that way if those troops hadn’t been able to cross the Connecticut River right here on our ferries. The way I see it, our ferries helped win the revolutionary war.”

“Very good, Raymond. Another important date anyone?” Mrs. Gerard said, looking directly at me.

I stood next to Mrs. Gerard’s desk, faced my 4 classmates, and said, “Yes, ma’am. September 6, 1781.” I unfolded my hand-written pages and read out loud.

![]() “My story is about a boy named Daniel Williams, who was 14 years old on September 6, 1781—same age as I am right now. He lived right here in Saybrook, and went to school right here, just like we do.

“My story is about a boy named Daniel Williams, who was 14 years old on September 6, 1781—same age as I am right now. He lived right here in Saybrook, and went to school right here, just like we do.

“One day a neighbor, a Connecticut militia fighter stationed at Fort Griswold in Groton, came home on furlough and asked Daniel if he’d like to stand his duty at the Fort for those few days. Although there had been false alarms, there had been no attacks on the Fort in a long time so Daniel’s parents decided it would be safe for him to go. His mother sewed a new red flannel shirt for him to wear for when he met the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel William Ledyard.

“After 2 days at the fort, Daniel had learned the names of many of the Connecticut militia fighters; four were from Saybrook, like Daniel.

“Sunrise on his 3rd and last day at the fort, September 6, a lookout spotted two British sailing ships entering the mouth of the Thames River. This was very bad news for Daniel and all the militiamen inside the fort. A militiaman sounded out an alarm on his bugle horn.

“The British had 600 men in official red uniforms with brass buttons and fancy hats; the Connecticut militiamen had no uniforms and no fancy hats. The British soldiers carried new muskets and had canons that could fire from the ships and reach the Fort. The Connecticut militiamen brought their own muskets from home. Lieutenant Colonel Ledyard was very worried.

“The militiamen had two advantages. They were on top of a hill, and inside the protection of a fort so they were able to fire down on the British as they climbed up the hill. The militiamen killed many British soldiers.

“The loss of his soldiers at the hands of so few and poorly armed militiamen made Major General Benedict Arnold very angry. His British officers ordered their soldiers to force their way into the fort and attack.

“Daniel couldn’t escape. He watched as Lieutenant Colonel Ledyard stood tall and respectfully surrendered his sword to a British officer.

“Instead of calling off the attack, that British officer accepted Colonel Ledyard’s sword and then stabbed him in his side, killing him with his own sword. Daniel stood and watched as it happened, frozen with fear.

“Didn’t the British know the militiamen had surrendered? Muskets continued to fire all around Daniel. A militiaman right next to Daniel was hit with a bullet in his head; there was blood all over him.”

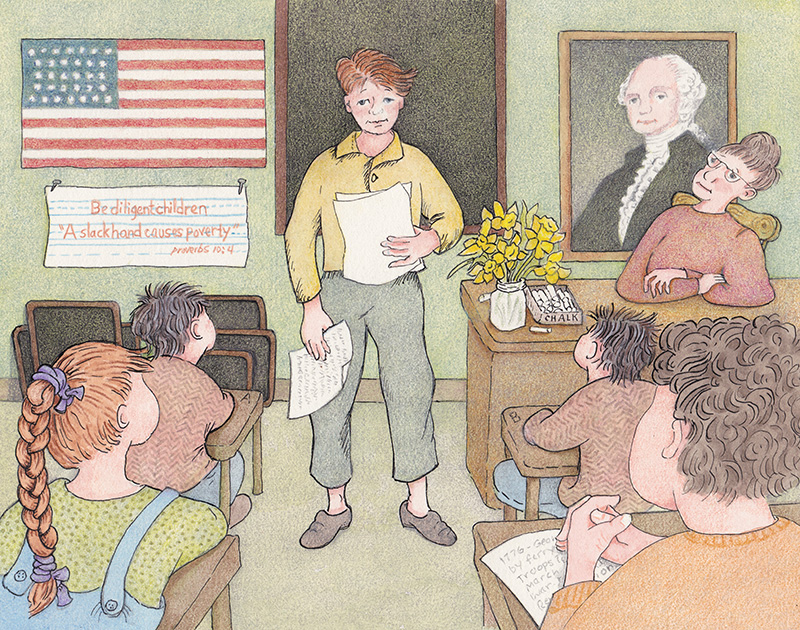

![]() “Yuck!” Ben shouted out.”

“Yuck!” Ben shouted out.”

“Double Yuck!” his twin brother, Adam, echoed.

Clara said, “Daniel should have found a place to hide.”

“Not possible,” Ray said, “The militiamen were out-numbered.”

Clara stood and asked, “Why did Daniel’s neighbor take those days off? Did he know ahead of time there was going to be an attack? Maybe he was a traitor, like Benedict Arnold.”

“What about Ashley?” Ben asked. “Is she our enemy? She’s British.”

“I’m an American,” Adam said, saluting the painting of a flag on the wall.

“We’re all Americans now,” Ray laughed. “We’re not loyal to a king anymore; or President Buchanan either. We’re loyal to the flag.”

They were all talking at once. I had lost control of my audience and didn’t know how to get it back, so I shouted, “Do you want to hear the rest of my story, or not?”

“Class,” Mrs. Gerard said, softly, “Let JJ finish his story, please.”

“Well,” Clara said plopping down onto her chair, “I still wonder why Daniel’s neighbor all of a sudden decided to take three days off.”

Mrs. Gerard looked at me and nodded so I went back to my story.![]() “Like I said, a militiaman right next to Daniel was hit with a bullet in his head.

“Like I said, a militiaman right next to Daniel was hit with a bullet in his head.

“That militiaman thrust his powder horn, musket buck, and balls to Daniel, dropped to the ground and died.

“Every man around him was fighting; There was nothing left for Daniel to do but fight, hoping to maybe save his own life. A militiaman near-by shouted to Daniel, ‘You! In the red shirt! Over here! I need powder—now!’ Daniel ran to the aid of this fighter.

“As he passed the ammunition, Daniel was struck down by a British soldier’s bullet. He fell to the earth and died.

“Daniel’s parents came to look for his body among rows of dead British soldiers and Connecticut militiamen. His mother wept when she saw the red flannel shirt she had made especially for him to wear when he met Lieutenant Colonel William Ledyard. Now, Daniel Williams, the boy in the red flannel shirt and Lieutenant Colonel Ledyard lay side by side in death.”

![]() After I finished reading my story, everybody clapped in a quiet kind of way.

After I finished reading my story, everybody clapped in a quiet kind of way.

Mrs. Gerard led us on a walk out of the classroom and down Main Street, toward Saybrook Point. She stopped in front of an old iron double gate. “Cypress” was spelled out in iron letters on the left side of the gate; “Cemetery” on the right side. We walked through the gates until we reached Daniel’s grave.

Revolutionary War

Daniel Williams

Battle Groton Heights

died September 6, 1781

I just stared at that gravestone and thought about not living past 14. I thought about the sum total of me and my life etched on a single piece of granite.

I still don’t know what I’ll end up doing in my life, but I’m grateful to have more life and time in front of me to figure it out.

Four Saybrook Connecticut militiamen and 14-year-old Daniel were killed in the Battle of Groton Heights at Fort Griswold, September 6, 1781. Their bodies were returned by ferry to Saybrook. They were John Whittlesey, Stephen Whittlesey, William Comstock, Jonathan Butler, and 14-year-old, Daniel Williams.

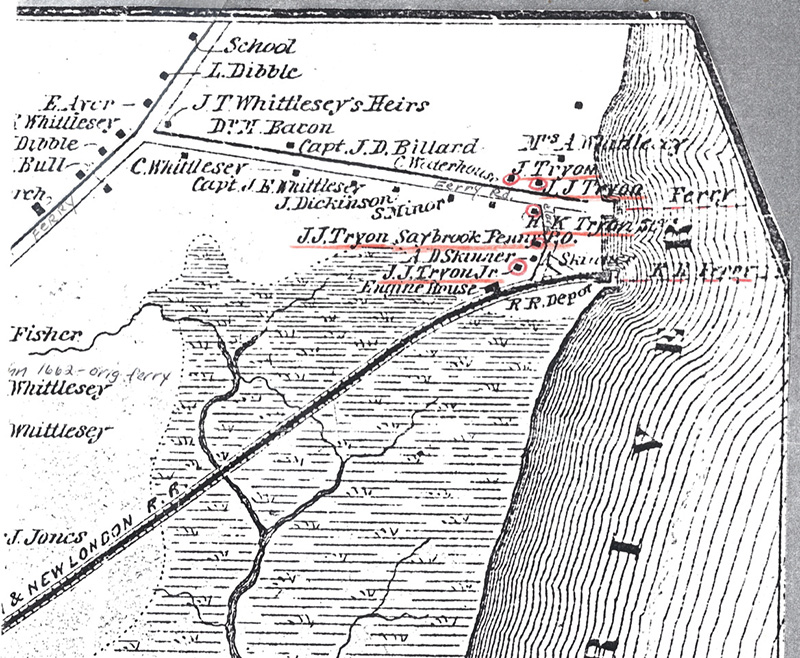

With the exception of Captain Henry Bramble, of Old Lyme, who served as a principal ferryman for nearly 40 years, most ferrymen passed through history without notice. Were it not for an 1859 map of the Saybrook ferry landing showing numerous JJ Tryon’s, I might never have been able to move beyond the simple knowledge that my own family had served as Saybrook ferrymen for many generations. Who knows? Maybe it was a JJ who ferried George Washington across the river from Lyme to Saybrook.