Walking slowly through the forest of sugar maple, white ash, and yellow birch, our path skirted the edge of a farm field abandoned long ago. My good friend Tim and I were in the wee hours of daylight of our first outing during Vermont’s Ruffed Grouse season. Even stronger than our high regard for this forest-dwelling, chicken family relative (of the order Galliformes) is the humble awe we silently share for the forest itself, now in its full autumnal blaze, conserved for today and for generations to come in the form of the Pine Mountain Wildlife Management Area.

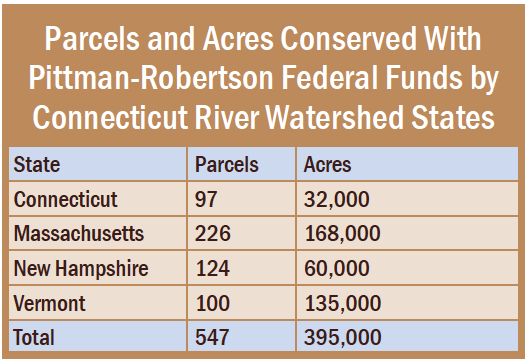

The 2,274-acre state-owned parcel, managed by the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department, is located largely in the town of Topsham, Vermont, but it also includes acreage in Groton, Newbury, and Ryegate. It is one of 100 examples of hunter commitment to wildlife habitat conservation in the state. Purchased with a combination of hunting-license dollars and federal Pittman-Robertson funds (an excise tax on firearms and ammunition authorized by the Pittman-Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act of 1937), lands acquired in this manner are mandated to be managed exclusively for wildlife and their habitat, and for wildlife-based recreation opportunities. Along with hunting, these opportunities include photography, bird watching, and general wildlife observation.

With our shotguns in a safe resting carry, Tim and I rejoined a favorite conservation topic of ours: the role hunters have played in developing the present-day conservation of habitat and the wildlife it supports. Our conversation began years ago during one of our first grouse hunts together, and without ceremony it is renewed each fall. Under the guise of a serious grouse hunt, we spend most of the time afield debating who we think is the most important figure in American conservation history. Meriwether Lewis? George Perkins Marsh? John James Audubon? George Bird Grinnell? J.N. “Ding” Darling? Aldo Leopold?

The list goes on and on with so many very important names. Deciding on a superlative always opens the door for more argument because someone’s favorite is certain to have been left out. In our case though, Tim and I seem to always gravitate back to Teddy Roosevelt. Tim, a real T.R. scholar, quoted him from memory: “The nation behaves well if it treats the natural resources as assets which it must turn over to the next generation increased and not impaired in value.”

Suddenly a grouse exploded from the tangle of grape vines and serviceberry on our right! Reflexively, but with molasses-like speed—still stunned by Tim’s penchant for Roosevelt recall—I started to pull up my Stoeger 20-gauge side-by-side. But Tim was on my right, so I quickly stood down awaiting the report of his Fox 16-gauge side-by-side. But our conversation and lack of attention to the field lead to yet another unused cartridge. Truth be told, our grouse hunts were more often an excuse to catch up on family and careers and to delve into the conservation issues of our times.

Our affinity for the president-conservationist stems from his recognition that wildlife is a national treasure to be held in public trust for present and future generations. Roosevelt, an avid hunter, and other hunter-conservationists of his time understood the direct connection between robust wildlife populations and the undeveloped land base that provides their essential life components of food, water, and shelter.

However, wildlife conservation on a meaningful ecological scale cannot be sustained by one person alone, even if that person happens to be the president. It requires a shared Roosevelt-like passion for wildlife and the natural world, one commonly found among North America’s hunters. For over 100 years hunters, have played a significant role in restoring and maintaining robust wildlife populations through collective actions that conserve wildlife habitat. On a local level, hunters of the four Connecticut River watershed states have been responsible for the conservation of almost 400,000 acres of wildlife habitat (see table).

“Tim! Did you hear that?”

“Tim! Did you hear that?”

“Yes,” he said with unbridled disappointment as we both recognized the flush of another grouse. This time just out of eyesight. Standing behind a Volkswagen-sized granite boulder scattered by the last glacial retreat, we should have had good cover from the grouse but, as we do too often, we underestimated the bird’s acute hearing and “street sense” abilities. Once again, we were focused on our conversation and not on our quarry. Our Achilles’ heel to be sure!

“Good thing we packed sandwiches,” mentioned Tim as he sat down on a big flat rock. It wasn’t close to lunch time yet, so I knew Tim was thinking about something else. “As much as I admire Teddy Roosevelt’s conservation legacy, I think the conservationist that moved us to a real personal land-use ethic was Aldo Leopold.”

“I couldn’t agree more,” I replied without hesitation. I could see Tim’s mind toggling between a discussion of A Sand County Almanac or making a concerted effort to be ready for the next thunder chicken surprise. We agreed to rededicate our time toward the grouse hunt.

As we prepared to head on, out from one of the many scattered hobblebush shrubs flew another brown bird. This one was much smaller and far more discreet. I caught a glimpse of its olive-brown body and white underside with dark spots on its breast. But most distinctively, even in that split-second, a rusty tail, a sure identifier of Vermont’s state bird, the Hermit Thrush.

“Great sighting!” exclaimed Tim. “How did you know it wasn’t a Wood Thrush?”

I quoted something Yogi Berra might have said, “Ninety percent of the time its 50-50,” I quipped. “Seriously though,” I went on, “the Wood Thrush would have had a rusty-shaded head and olive tail and would have appeared plumper.”

“John,” said Tim, “I think it is uncanny, but in all my circles of friends, including all of my natural resource co-workers, my hunting companions are among the best birders.”

After about two hours of steadfast attentiveness and diligent hiking, we reached the summit of Pine Mountain. Standing at about 1,500 feet above sea level and 1,000 feet above where the Wells River (passing along Pine Mountain’s northern border) meets the Connecticut, it is an unassuming landmark. In other words, you wouldn’t know it until you got there. No trails, no markers, no benches, no interpretive signs. Just the forest of hemlocks, spruces, firs, and of course, white pines eking out their living on the thin soil overtopping a massive granite knob too hardened for even the glaciers to move. However, if one peers to the east through the tangle of limbs and needles, the panorama of the Presidential Range of New Hampshire’s White Mountains comes into view. We found a fallen tree just below us that made a perfect lunchtime seat and took positions on opposite ends of the log.

As we began to savor our peanut butter and jam sandwiches, we both remarked, as if thinking the exact same thing, on how important fallen trees are as habitat features for a myriad of wildlife species. For example, squirrels use them as easy pathways through thick understory; when large enough, fallen trees often serve as wintering dens for black bears. One of the notable uses of a fallen tree is the famous displaying stage it creates for the Ruffed Grouse. On a larger and far more subtle scale is the necessary nutrient recycling that decaying trees provide.

As tempting as it was to bask in the brilliant October sun, we recognized the shortening of the day this time of year brings. We agreed to keep moving to take in as much of this remarkable area as we could. As we descended Pine Mountain on a northerly course, the increasing soil depth became evident when we reentered the hardwood forest.

As tempting as it was to bask in the brilliant October sun, we recognized the shortening of the day this time of year brings. We agreed to keep moving to take in as much of this remarkable area as we could. As we descended Pine Mountain on a northerly course, the increasing soil depth became evident when we reentered the hardwood forest.

“Tim, we have to check out Whitcher Mountain too. There is an errant stand of red oaks and hophornbeam that form an important feeding area at the summit and it’s only a short meander from our vehicles about a 30-minute hike from here.”

Whitcher sits on the northern border of the management area and it’s another granite knob that weathered the glacier. But it differs from Pine Mountain in that on its north side, sliding abruptly down to the Wells River, lies an esker of sand so fine you’d swear it was brought there from Cape Cod.

Just as we stepped into this unique part of the forest, suddenly and without warning out blasted a grouse from a thicket of raspberry canes. Gliding to my left, the grouse gave me a perfect swinging shot. This time I was ready. I pulled up, released the safety, and fired. As the grouse continued its glide to another thicket, safely out of range, I turned to Tim with a perplexed look of disappointment on my face.

“You were behind him again!” Tim said without hesitation.

“Yes, I know,” I said, sounding as disappointed as I looked. “Okay then, it’s back to the skeet range for some remedial practice.”

With our shadows growing longer and our vehicle still an hour’s hike away, we unloaded the shotguns and called it a day. Reaching the truck at dusk and saying our goodbyes, we promised to meet up again soon and shoot better. We concluded our parting by agreeing that, of all the grouse hunts we’ve shared over the years, this was by far the best of them. But then, that is what we say every time.

John Buck is a retired wildlife biologist from the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department. He spent his 39-year career managing white-tailed deer, migratory birds, and public and private forestland for wildlife habitat.