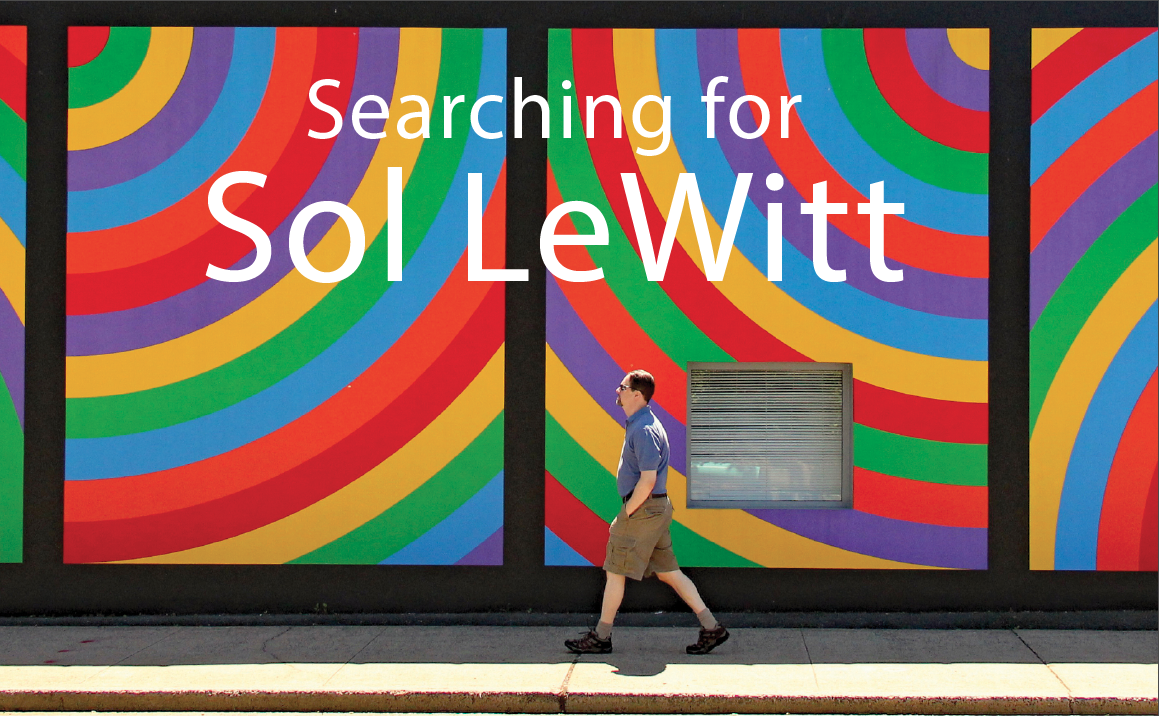

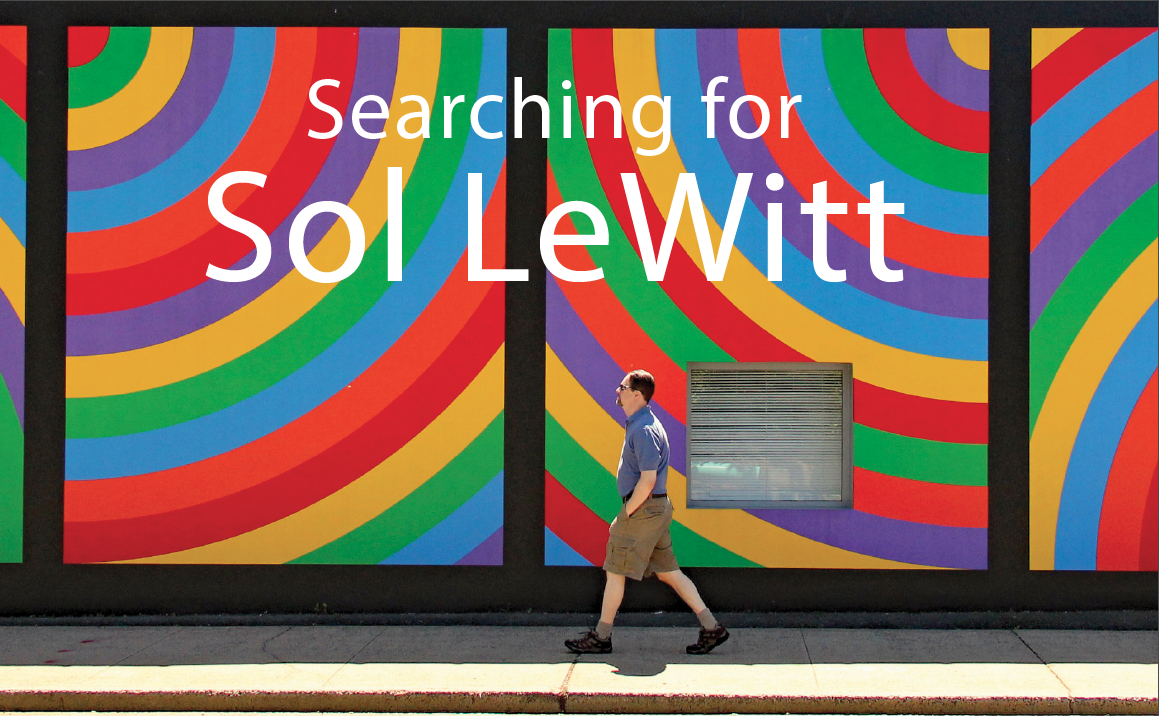

The author walks in front of a Sol LeWitte wall drawing #1105 “Colored bands of arcs from four corners.” Below: Barolo’s Chapel in La Morra, Italy (exterior and interior). Image Credit: Jack Keane

Many years ago, after attending a play at the Goodspeed Opera House, my wife, Amy, and I walked into Chester’s River Tavern. We were immediately struck by the colorful selection of framed prints on the walls, the design of which looked familiar.

“Isn’t that Sol LeWitt?” Amy asked.

We had recently visited the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art’s three-story factory building dedicated to his work, 27,000 square feet of wall drawings, one of the most extraordinary exhibits we had ever seen. So, why did this small restaurant have such a collection? We asked the waitress when she took our dinner order.

“Oh, Sol LeWitt and his family lived here,” she replied.

“In Chester?”

“Yes, right down the street.”

This was news to us, and as we soon learned, that’s the way LeWitt had wanted it.

Barolo’s Chapel in La Morra, Italy (exterior and interior). Images Credit: Getty Images/Coscarella Gianfranco

Born in Hartford in 1928, young Sol was soon forced to move to New Britain with his widowed mother, down the road from the Museum of American Art. Finding work in his aunt’s store, he spent many hours scribbling on wrapping paper. His mother noticed his interest in drawing and took him to classes at the Wadsworth Atheneum. By the time he applied to college, he was confident about his career choice, majoring in art at Syracuse. After being drafted for the Korean War, he moved to Manhattan, working at several jobs before finding steady employment at the architecture firm of a young I.M. Pei. It may have been at this job that he began to change his mind about the place of the artist in the art world. After all, there may be celebrity architects like Pei, but mostly the practice is invisible, an art in which other people build according to your designs.

This experience may be one reason LeWitt rejected the personality culture of Abstract Expressionism and searched instead for the “building blocks of form.” He used geometrical designs to craft sculptures and paintings, removing elaboration and stripping things down to their essential structures. He experimented with mathematical ratios and skeletal designs. By the time he was 40 years old, he had developed his own unique style, backed by a radical aesthetic: the artist is not the most important element, and neither is the object the artist created. What is important is the idea behind it. He put it this way: “Ideas can be works of art; they are in a chain of development that may eventually find some form.”

With a series of minimalist, industrially-fabricated sculptures, he earned inclusion in a 1966 exhibition at New York’s Jewish Museum. Then, in 1968 at the Paula Cooper Gallery he took his idea farther, drawing on the wall a system of parallel lines in four different directions, knowing that at the end of the exhibition, it would be painted over. Bemused patrons found that they could not “buy” that work of art. Instead, others could re-create it on other walls, a design that could be reproduced like many houses from one architectural plan or performances from one musical composition.

To allow the creation of these wall drawings, LeWitt wrote instructions, some like maps, some like mathematical formulas, some as simple paragraphs. For example, Serial Project No. 1 states, in part, “A set of nine pieces is placed in four groups. Each group comprises variations on open or closed forms. The premise is to place one form within another and include all major variations in two and three dimensions. This is to be done in the most succinct manner, using the fewest measurements. It would be a finite series using the square and cube as its syntax.” The drawings could be completed by anyone, given enough patience and craftsmanship. This method was often compared to a new language, and his art was described as “conceptual” art. “Conceptual art is made to engage the mind of the viewer,” he wrote, “rather than his eye or emotions.”

These meticulous, repetitive, and nearly impersonal designs gave the impression of simplicity, like the abstracted ripples of a river or the ridges of a mountain. By the late 1970s, many museums began to buy this art from him, or rather, buy the rights to put it on their walls, since there were no “objects” to buy. Depending on the size and shape of the museum walls, the work would change, “a necessary part of the wall drawings,” as LeWitt said. Furthermore, errors were “part of the work.”

Despite his international status, in 1980, LeWitt’s public art project—a mural for the reconstruction of the Civic Center—was rejected by his hometown city of Hartford. Indeed, the Courant and many of its readers railed against his design. Nevertheless, the Wadsworth gave him a retrospective a year later, with 51 miles of lines in one wall drawing alone. Other museums followed. He moved to Spoleto, Italy, and as the decade progressed, he worked more and more with bright acrylic paint, creating serial images in different primary colors that seemed to pulse on the walls.

Through all his success and all his work, he remained elusive, shunning the spotlight, believing the work itself spoke better than he could. In our readymade celebrity culture, this was a refreshing anomaly. He and his wife, Carol, donated Wall Drawing 763C to the Atheneum to brighten up the lobby. But he famously ruined a party held in his honor there, refusing to be the center of attention, actually stopping people mid-speech when they praised him. He dodged openings of exhibits, refused to “network,” didn’t talk to reporters, and hung up on people asking for his time.

Later in the 1980s, he moved back to his home state to the village of Chester on the Connecticut River. “For Sol, Connecticut was always home,” said his wife Carol in explanation. The artistic, educated, slow-moving culture of the river valley appealed to him, reminding him of both his recent years in Italy and of the best parts of his childhood. He also wanted to be close to the center of a quiet village, close enough to walk down to get his morning paper or eat at the Lunch Box Café. He and his family moved into an 1820 house and painted the kitchen electric yellow and built a beautiful and practical studio of wood and glass in the backyard. Every morning from 8:30 to noon he spent in that studio, while his daughters Sofia and Eva attended the local schools. For two decades, he became a fixture in town, attended the Beth Shalom Rodfe Zedek synagogue, and even exhibited his work at the tiny Chester Gallery.

Barolo’s Chapel in La Morra, Italy. Image Credit: Getty Images/Coscarella Gianfranco.

Even as he retreated to this small town in cranky solitude, he continued to be generous to fellow artists, creating opportunities with his wallet as well as his connections. Shortly after his daughter’s bat mitzvah was interrupted, his displaced congregation decided they needed a better place to worship. He and local architect Stephen Lloyd worked on the project, including his amazing star design for the ark that holds the Torah. Sol was “not a friendly human being,” said friend and fellow conceptual artist Lawrence Weiner. “Not a saint.” And yet, though he didn’t want attention from most people, he put his skills to use helping his community.

The three-story exhibition at the MASS MoCA went up a year after he died in 2008, painted on the walls by assistants and graduate students, a tribute to his radical concept that the “idea makes the art.” Soon, his work was everywhere, a worldwide phenomenon, an undeniable presence from the walls of Microsoft to the New York subway, from Paris to Australia. A generation of artists has sprung up, influenced and inspired by him, a generation that includes his daughter Eva LeWitt and her vibrant, handmade sculptures and wall hangings.

Though Sol LeWitt died almost fifteen years ago, the walls of public and private institutions across the planet continue to be transformed into mathematically precise murals, sometimes in bright, eye-straining colors, sometimes in pastels, sometimes in black and white. They last as long as the buyer pays for, perhaps a year or a decade, and then they disappear. But new ones will keep appearing, probably as long as there is a market for art. It is LeWitt himself that truly disappears. There are few biographies of his life, with Lary Bloom’s recent biography from Wesleyan University Press a lonely exception, and even that book focuses on the ideas more than the man. That is probably how the man himself would have wanted it. We take too much delight in building up and tearing down celebrities, and this year’s famous artist is next year’s forgotten meme. But it is more difficult to tear down his art, difficult to forget the work that he did.

On a trip to Holland ten years after my wife and I had visited the startling rooms of the MASS MoCA, we found his work well represented. After all, the Dutch had embraced LeWitt early in his career, declaring him one of the best contemporary artists in the world. At one museum, the woman taking our tickets asked where we were from.

“Connecticut,” we answered.

“Ah, Connecticut!” she said. “Like Sol LeWitt.”