Come June I’d rather be out on the open marshes, or the rolling plains of North Dakota or Saskatchewan. But from the first few dreamy days of April on well into May, where better to discover springtime than in one’s own patch of cozy, quaint New England woods?

I have a favorite patch in the State Forest up in Lyme, Connecticut, a few miles north of where I live. It’s rolling, rocky oak woods, mostly, and all second growth of course—it was all open farmland not so long ago—but it’s remote and quiet, far enough away from any nonsense, and within it lie two pristine ponds, bare granite outcrops, and cliff faces hung with columbines and spleenworts; and long winding brooks that find their way downhill into a deep arterial stream, which glides on through a swampy lowland of Red Maple, spicebush, and spring pools strewn with the neat round clumps of tussock sedge, their old straw bristling with new green.

A dirt road runs through these woods, and every year I like to walk it just to see the first white puffs of shadbush, the first wood anemones and bloodroots punched up through the duff; and along brooks the new unrolling ferns, and new grass needling up through old. I like to listen, too: for the first barking wood frogs, or the brusque call of an early phoebe; or the creaking of a lone spring peeper, trying out his peep too soon.

Spring peepers: the mere mention flings me back to an electrifying moment of now nearly 50 years ago, which mystifies me still. I was hiking up along the river late one April afternoon with my big 4x5, looking for photographs, and having gained the top of a long hill at last I heard the shrilling of what had to be a million peepers—or no, two million. But where were they?

I walked on, soon gained another hilltop and looked down to see two granite promontories jutting out into the river—“whalebacks,” they’re called locally—and what should fill the gaping cove between them but a cattail marsh. So there, that’s where they were! And at this lesser distance now the shrilling was no longer of a million or two million voices but a single all-pervading roar, which I can only write as eeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee.

I stood transfixed, just listening: it seemed that something was about to burst. Then suddenly, as if a switch were flipped—it stopped.

What had I done? I looked around, down at the marsh, then up—and there, high in the evening sky above the cattails…it was a lone silhouetted Great Blue Heron, winging slowly home across the valley. But really, way up there? A passing heron: that’s what had instilled such terror in the marsh below? I laughed aloud.

The bird flew on, and in its own good time; then passed from view. I waited, but the evening was dead silent, still. Then a lone voice began to quaver, a few others dared chime in, and within seconds the whole marsh was roaring as before.

I laughed again, and turned for home: so much for photographs. But I got thinking, and I don’t know how they could have done it. All those voices had stopped short at once, from one end of the cattails to the other: all, in a split second. The communication; the celerity. So, which one had flipped the switch—and how?

But I was speaking of my patch in the State Forest, and spring brooks. For years it was the brooks that I sought out to photograph in early spring; and one brook in particular.

Each evening after work I’d make a beeline for this little brook, hike up along it with a camera and explore its elfin falls and eddies, bubbling pools and mossy boulders: always in April, when the spray-soaked mosses burst with wood anemones and early meadow rue, dwarf ginseng, and three kinds of violets—whole islands, galaxies of flowers. I’d set up and burrow in, investigate, and then if something lit up on the ground-glass screen I’d work in close, frame up a piece of it, and take it home with me.

Sometimes I’d bring my little black doggy, Eliot, and after a long spell under the focusing cloth I’d look up and around to find him perched nearby on some half-buried boulder, keeping watch and sniffing, sifting through his springtime world; and then on seeing all was well, I would return to mine.

By mid-April the spring woods are quiet, still. You hear a few persistent peepers, and the twittering of swallows—Tree Swallows, passing high above the trees or sweeping low over the ponds—and the assuring purr and gurgle of the brooks; but little else.

And then it happens. Powder blue spring azures light up at your feet, flit off and flicker through the woods like burning bits of the blue sky itself then poof, they’re gone; and overhead a pert blue little bird is fussing in the twiggy haze, and trying to be heard: a Blue-gray Gnatcatcher. His idea of birdsong is a running gibberish of mews and whisperings so thin it might elude your ear.

Any day, the first lights of the warblers will appear: the sunny yellow Palm; then Pine; and then before the month is out, you’ll hear the first Louisiana Waterthrush, his clear notes ricocheting up or down a brook, then breaking down into a spluttered jumble: as if he had forgot the plan, and had to get the notes out in a hurry. And the next might be a neat-striped Black-and-White, creeping up around the trunk of an old, weathered oak and picking from the clefts. So fresh and clean a bird, the male, brand-spanking-new against the ancient gray of bark: it seems he might have burst from a cocoon that very morning.

Any day, the first lights of the warblers will appear: the sunny yellow Palm; then Pine; and then before the month is out, you’ll hear the first Louisiana Waterthrush, his clear notes ricocheting up or down a brook, then breaking down into a spluttered jumble: as if he had forgot the plan, and had to get the notes out in a hurry. And the next might be a neat-striped Black-and-White, creeping up around the trunk of an old, weathered oak and picking from the clefts. So fresh and clean a bird, the male, brand-spanking-new against the ancient gray of bark: it seems he might have burst from a cocoon that very morning.

And then come May, the warblers drop in by the score: some for an hour, or day, and some the summer long. Some mornings find the treetops winking with the yellows, oranges, yellow-greens and blues of Nashvilles and Magnolias, Blackburnians and Redstarts, Black-throated Greens and Blue-wings, and the beautiful Parulas: steel-blue above and gold below, and unmistakable for that clean snappy sizzle of a song. And most sublime of all, perhaps, is the Black-throated Blue. There’s something irresistible in that no-fuss arrangement of deep dreamy blue and black, and white below.

So many warblers, and so many color schemes, and they all work: there isn’t one hack job among them. And those cited here are but a few of the more common ones. About a dozen others can be seen or heard without too much exertion, some of which remain to nest: including the breathtaking Hooded, and the ill-named Worm-eating (a warbler that neither feeds on worms, nor warbles). They both reach their northern limits here in southern New England.

The last two common warblers to pass through, the Blackpoll and the Tennessee, keep to the leafy treetops, where they are most difficult to see. But their distinctive songs will tell them, every time.

Come June the nesting birds are settled in and little seen or heard, increasingly; and soon the woods are filled in thick with green, and gloom. The wood anemones and azures are long gone, and I’m gone too.

William Burt is a naturalist, photographer, and writer with a passion for wild places—especially marshes—and the elusive birds few people see. His photographs and stories are seen in Smithsonian, Audubon, National Wildlife, and other magazines, and he is the author of four books: Shadowbirds (1994); Rare & Elusive Birds of North America (2001); Marshes: The Disappearing Edens (2007); and Water Babies (2015). He lectures often, and his traveling exhibitions have shown at some 35 museums across the US and Canada—including the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, the New Brunswick Museum, the Calgary Science Center, the Liberty Science Center, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, and the Harvard Museum of Natural History.

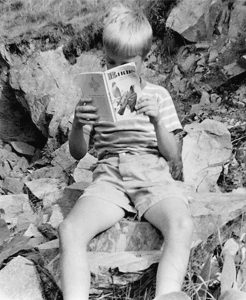

A young William Burt studies Birds: A guide to the most familiar American birds. Image courtesy of William Burt.

A new term is required to describe William Burt, whose photography and prose regularly grace this magazine. Neither nature photographer nor naturalist do him justice. His stunningly intimate portraits of birds that few people have heard of, and fewer still will ever see—certainly not in the environs where Bill captures them—rise to the level of fine art.

Never mind his evocative descriptions, Bill Burt’s images alone tell stories. They can be poignant, endearing, arresting, or, on occasion, hilarious. In addition to wonder, Bill and Mother Nature share a sense of humor.

Starting out from his home in Old Lyme, Bill has traipsed across North America stalking the likes of black rails in Maryland, eared grebes in Saskatchewan, and black-necked stilts in Florida.

To acquire studio quality photographs of his reclusive subjects, Bill built and lugs a portable studio with him into the prairies and marshes so he can get the light just right. To position himself within 10 feet of skittish marsh species, like the purple gallinule, he deploys and inhabits his floating blind that he designed for the purpose.

Spending five hours belly-deep in chilly water is sometimes required. If there were anyone else around, they would laugh at the sight, particularly when he and his cumbersome accessories have to slosh for cover from advancing lightning storms.

Five hours is nothing to Bill when he is on the prowl. He spent seven years on his fourth and most recent book, “Water Babies: the Hidden Lives of Baby Wetland Birds” (W.W. Norton, 2015). Just finding the nests of 43 species was tricky business. For the black-crowned night heron he traveled to a remote prairie marsh in North Dakota, where the birds nest in accessible shrubbery rather than atop tall trees, as they do in New England.

The results of his pioneering efforts are clearly worth it. His portrait of the aforementioned heron’s nest overflowing with chicks or, as he described them, “The most God-awful creatures you’ve ever seen in your life,” is riveting—particularly when contrasted with an accompanying image of the elegant mother they will one day resemble.

In addition to his books, Bill Burt’s writing and photography have enhanced publications such as the Smithsonian, Audubon, and National Wildlife. His work has been exhibited in museums across the continent, including the Connecticut River Museum in Essex, Connecticut.

The reviews of Bill’s work have been invariably positive, including this clincher from the late Roger Tory Peterson, who was a photographer himself, guru of modern bird watching, and author/artist of the influential Field Guide to the Birds of North America. Peterson opined, “William Burt is a perfectionist whose photographs of rails and other shy and elusive birds of the wetlands are unquestionably the finest ever taken. I admire his technical skill and perseverance in getting these pictures. He has set a new standard.”

When people marvel at his patience, Bill Burt’s reply is telling: “I explain that it is very easy to be patient if you want something badly enough.”

—David Holahan