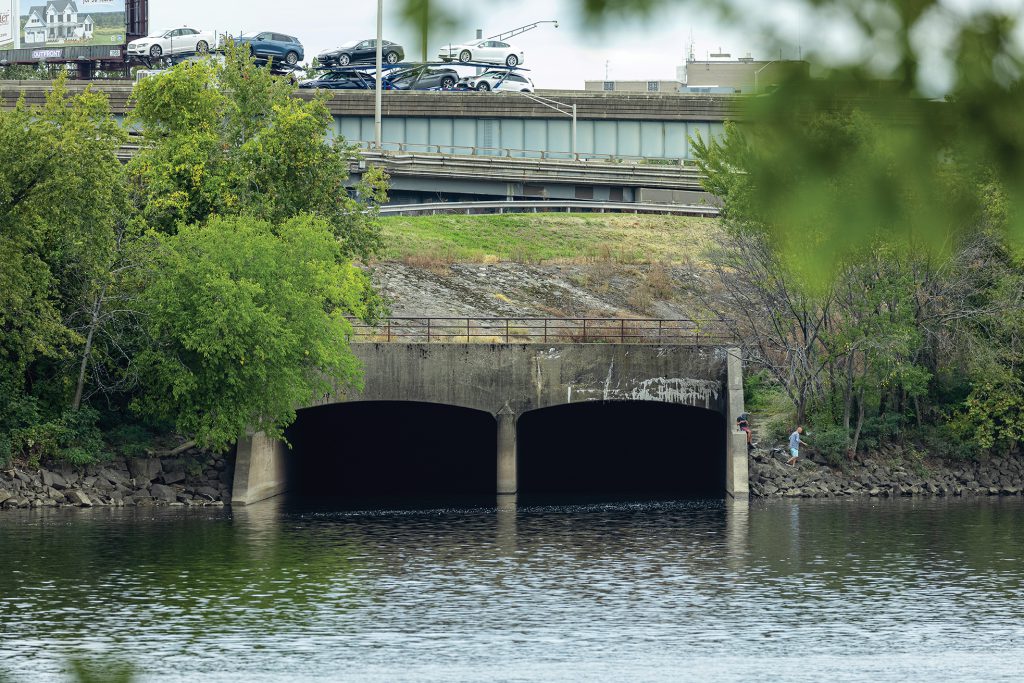

The Park River flows through two massive conduits that run under the City of Hartford and into the Connecticut River. Image Credit: Christopher Zajac

I knew it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity the minute I got the call—a chance to go where few people have been before without leaving Connecticut. John Kulick of Huck Finn Adventures invited me and our small staff at Connecticut Explored (the magazine of Connecticut history formerly called Hog River Journal) to take a canoe trip down the Park (formerly called the Hog) River in Hartford. I felt compelled to take a ride down our publication’s namesake river.

I’ll admit though, I was nervous. I knew the waterway’s colorful history and I knew that the trip would be underground. Sixty years earlier, the hard-to-control river had been buried.

The Park River empties into the Connecticut River just above Charter Oak Landing in Hartford. Along its banks is where the city was settled in 1635, after the Dutch built a trading post in 1633 near the Wangunk village of Sukiog.

Before it was the Park River, it was the Little River, then the Mill River, and then the Hog River—a series of names that reveals its history. As Hartford grew, mills and factories, tanneries, a dye house, pigsties and slaughterhouses, brickyards, and tenements were built along its banks and used it to dispose of industrial and human waste. In the 1860s both Jewell Belting Company (which made the belts that every factory needed to operate machinery) and Sharp’s Rifle Manufacturing (a supplier of rifles to the Union Army) were major industrial powerhouses.

Left: Jewell Belting Company dumped its industrial waste into the Park River. Illustration from a Hartford Board of Trade publication, 1889. Top and Above: The Park River flowed through Bushnell Park before it was buried in the 1940s. The park was built in the 1850s to beautify an industrial section of the city. Images: Library of Congress

Newspaper accounts told of dead fish and cats, the slimy surface, and the smell. Despite these conditions, it was renamed the Park River when Bushnell Park was built along its banks in the 1860s. Park construction cleared the area of a railroad spur and its service yard of sheds, garages, piles of ashes, and cinders. Also cleared were squatter shacks, pigsties, and garbage dumps.

When Mark Twain built his house in the city in 1874, it overlooked the river’s north branch. But renaming the river did not reduce the pollution or the destruction caused by frequent flooding. When the Connecticut River was high each spring, it backed up into the Park River.

After the catastrophic floods of 1936 and 1938, federal funding financed a plan to protect the city from its little river. The federal government’s motivation derived from both an increasing awareness of the river-borne public health hazard and the need to protect Hartford’s burgeoning defense industry. The project, completed in the early 1940s, included a system of dikes along the Connecticut River and twin underground concrete conduits 30 feet wide and 19 feet high to bury the Park River.

My Ride Down the Hog River

Since the 1990s, according to David Paulsen in a 2007 story for the Hartford Advocate, Kulick had been guiding canoe trips down the Park River conduit—a 2-mile trip that as many as 250 people had taken by then. Kulick was forced to stop his “Lost Park River” tours, though, in June 2004 by the City of Hartford, due to safety and liability concerns. My trip the previous August was part of Kulick’s effort to stave off this action by convincing the city council that the tours were a benefit to Hartford tourism—and safe. Along on my trip was city council member Hernan LaFontaine.

The river, barely a babbling brook in late summer, looked innocent enough. As we entered the pitch-black conduit, outfitted in life jackets, headlamps, and glowsticks hanging around our necks, it felt like going into a fun house ride, waiting for scary things to jump out at us from the dark. Only our headlamps illuminated the concrete walls and the reflective surfaces of flotsam and jetsam: a shiny bicycle reflector, metal grocery cart, and a couple of lost basketballs. Fortunately no native, urban “fauna” scurried by. At the point at which we were approximately underneath the Hartford Public Library, we headed down a slight incline, picking up speed on mini-rapids.

Further on, the air became so humid and thick that even my headlamp could not illuminate past my canoe partner in the bow. Kulick had us turn off our headlamps and float in the absolute darkness and quiet under the city: near complete sensory deprivation—spooky! We banged our paddles on the sides of the canoes to hear the echoes.

The entrance to Park River conduit from the north branch of the Park River, Hartford, 2007. Image Credit: Elizabeth J. Normen

About two and a half hours into the trip and now having to put some effort into our paddling against the surge of the Connecticut River, we took a slight turn and saw the light at the end of the tunnel. Whereas the water had been shallow and the head clearance high when we started, now the water was deep, and the head clearance low. Our small flotilla emerged blinking into the bright sunshine; we paddled past city kids fishing and pulled out at scenic Charter Oak Landing.

A few months later, Kulick seemed to have prevailed when, Paulsen reported, that October the city council, “calling the tours ‘immensely popular…educational and informative,’ voted to negotiate a contract with Kulick for use of the Park River,” with proper insurance and safeguards. But before that contract was

Exiting the Park River conduits where they empty into the Connecticut River above Hartford’s Charter Oak Landing, tour led by John Kulick of Huck Finn Adventures, August 2003. Image courtesy of Connecticut Explored

negotiated, the city’s newly appointed corporation counsel nixed it, again citing liability concerns.

Though entering the conduits is off limits today, a quick Google search will find individuals who have canoed the river through the conduits in recent years. These urban adventurers purport to have done their research to avoid taking the wrong branch which goes by exhaust vents of the nearby steam plant, the deep overflow pit, and—importantly—a flash flooding event.

The River’s Future

The Park River’s watershed covers 77 square miles, from the Metacomet Ridge on the west to the Connecticut River on the east. Its impact and influence reach far beyond the city’s boundaries.

Mary Rickel Pelletier of Park Watershed leading a tour of the north branch of the Park River for Hartford Preservation Alliance, 2007. Image Credit: Elizabeth J. Normen

The city is not unconcerned about the river and the role it might play in the city’s future. In 1999 it commissioned an assessment whose findings touted the Park River as a major environmental asset. Despite finding less-than-perfect water quality, the investigators spotted great blue herons, a green heron perched on a shopping cart, and mallard and wood ducks. They found evidence of deer, coyote, and fox. A 1988 fish survey noted pickerel, abundant blacknose dace, large-mouth bass, and a handful of other varieties of fish.

Two miles of the river remain buried, but efforts continue to protect the river and its watershed. Visit ParkWatershed.org to find out what is currently happening to raise awareness of the river and include it in regional conservation planning efforts. Visit CTExplored.org for a more detailed history of the Little/Mill/Hog/Park River.

Elizabeth Normen is founding publisher of Connecticut Explored, the nonprofit magazine of Connecticut history. She has an MA in American Studies from Trinity College. She is coeditor of African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014), and two books for children: Where I Live: Connecticut (2017) and Venture Smith’s Colonial Connecticut (2019).