Chapter 3: Squire

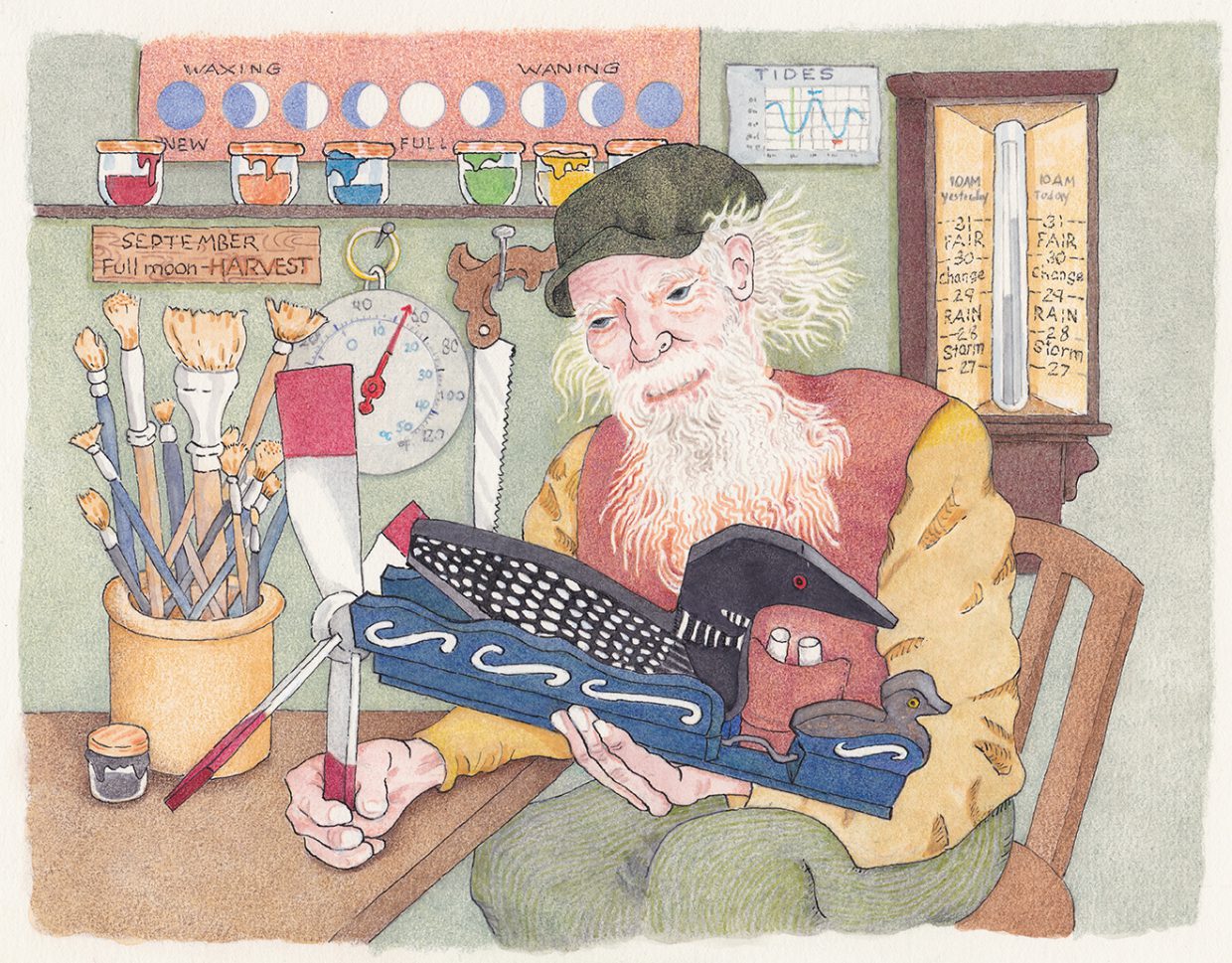

“Morning, Squire!” I say it nice and loud to his back, not sure he hears me. As soon as he finishes chalking today’s weather prediction on the big blackboard outside the Neighborhood House, he tucks the chalk pieces into his vest pocket, gives that pocket a little pat, turns around and looks surprised to see me.

“Ah,” Squire says, tapping two fingers on the brim of his old green cap. “And a good foggy morning to you, JJ.”

“Mum charged me with delivering these two spice cakes, one for you; and one for Grandfather JJ.”

“Your mother, she’s as kind as a warm zephyr on a sunny day.”

As we start out walking back to his cottage in the boatyard, he turns and looks at me in a quizzing sort of manner. He raises his eyebrows and says, “Zephyr? JJ?”

“Oh spit. I know this, Squire. One of the eight wind deities. Greek. A Zephyr wind is from…the west?”

“That’s right, JJ, you’re learning your winds.”

I pray deep inside that he doesn’t ask me what the other seven deities are because the only other one I can recall on the spot is Boreas, the north wind.

“And where, JJ, do you suppose the tide is right now?”

“That’s an easy one, Squire. Low, because the air stinks like rotting fish!”

“Look, JJ,” Squire says as he watches his long wispy, white beard lift up off his shirtfront and blow toward his right ear. He laughs, “Ten-knot wind out of the north. See? Even my beard can be a wind direction and speed indicator. Remember that poem I read to you, JJ? ‘The Wreck of the Hesperus’? Like my beard, when the skipper watches the smoke from his pipe: ‘He watched how the veering flaw did blow, the smoke now west, now south.’”

“I sure do remember that poem,” I say. “Everybody on board dies in the end. The captain tied his daughter to the mast to keep her safe, which was a really dumb idea, because that meant she couldn’t escape. Then he died and she froze to death, and the crew all drowned and the ship was wrecked on a reef.”

“That skipper was warned, but he didn’t pay attention to the signals the weather was sending him and what the old seaman said. He was ‘scornful’ and arrogant and thought he could outsmart the weather.” Squire shakes his head and says, “Foolish skipper, indeed.”

Just as Squire pushes open his front gate my five-year-old twin cousins, Adam and Ben, who make a habit of playing in Squire’s front yard among the forest of whirligigs, come running up the path toward us pulling their rescue cart behind them. Clara, their sister, is running along behind the cart clutching a chicken to her chest.

Breathless, all three spit out a story in pieces.

“We seen him…”

“He… Squire… He stole one of your…”

“A whirligiggle…”

“A loon…”

“He knew we was watching him, too…”

Then, all three, at the same time, point, “Quick, JJ! You can catch him.”

I run past the three kids and around the chicken coop—that’s when I spot the loon whirligig lying under a skiff. “I watched him disappear into those woods,” I say, handing the whirligig back to Squire. “Judging by his size, he couldn’t be any older than nine or ten years old.”

“I would have given it to him,” Squire says, “after we had a little man-to-man chat, rather than have the lad marked for life as a thief.”

He turned to Clara and says, “Child, what’s distressing my laying hen?”

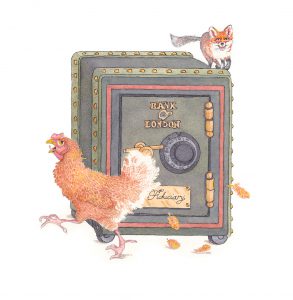

“A fox was chasing her, Squire. She was running toward me, jumping up into the air and squawking like chickens do when they’re scared. When I picked her up the fox ran away.”

“That fox has been trying to kill one of my hens for days now,” Squire says.

“Did you see the notice on the Town Hall board, Squire?” I say. “You can get one-dollar cash money from the Saybrook Town Treasury for the head of each fox you kill; there’s a bounty for woodchucks, too, but it’s just twenty-five cents each. There are a few restrictions, though, like you can’t shoot a fox in January or February, but this is September so you can do it now. Another restriction is you have to prove you shot the fox inside the Saybrook village limits, and that you didn’t do it on a Sunday. Then you can take the dead fox in and collect your dollar, but I could be your witness, and then I could take it for you, if you want me to, so you wouldn’t have to walk all the way up to Town Hall.”

“Thank you, JJ, but what I shoot, I eat, and I never heard of eating fox.”

As I leave, Squire shouts after me, “Wind’s up this afternoon, JJ.”

I turn around and wave, “Thanks, Squire, I’ll remember.”

I hear him shout again as I open his gate, “Twenty knots or more.”

I give a little wave, but don’t turn around and look back.

“Out of the northwest,” he shouts, but I am out of his sight by then.

“Squire sure talks about the weather a lot, Grandfather. He’s always got one more thing to say about it.”

“He has every reason, JJ. His precious wife and their home were swept out to sea in a violent gale.” He squints his eyes like he’s trying to remember, then says, “September 23rd it was, 1815, was called the Great Gale. If we had known it was coming, we would have evacuated.

“Back then Squire’s estate at Ragged Rock Creek had a house perched on a rise in that way that grand houses do so as to be noticed and to take in the best views. Squire was after important business upriver in Middletown when that big wall of water rolled first over Fenwick Point, the Fort, then over Ragged Rock and up into Saybrook; when it washed back out to sea it took his wife, his house, and left boats and ships washed up on the land. Poor Squire, he also lost a fortune in bank notes, gold coins, jewelry, and silver that he kept in an old iron safe.”

“What happened to that safe, Grandfather?”

“What happened to that safe, Grandfather?”

“Squire never said. The little cottage where he lives is the only building left on his estate now. Since the Gale, he has devoted all his waking hours to studying the weather. He taught himself about weather prediction and has been passing his knowledge on to the mariners and the townsfolk ever since.” Then Grandfather laughs, “He’ll tell you about the weather, alright, even if you don’t ask him.”

“But how does he make money?”

“I think by now every citizen of Saybrook has one of Squire’s hand-carved whirligigs in their yard, or one of his weather vanes on their roof; over in Lyme, too. And remember, he sells eggs when his hens are in a generous laying mood.”

“He can’t live on those kind of sales, Grandfather. Besides, he had a fortune in that safe. He didn’t have to work; you said so.”

“Don’t forget, JJ, he walks an hour every morning up to Ferry Point just so he can predict the day’s weather on that big blackboard—temperatures, air, and water; tide cycle for the day; winds, currents, too; and if we should expect rain, fog, snow, or ice. It’s his gift to the mariners of Saybrook, and the currency he earns is our respect, and the occasional ginger cake.”

“But, Grandfather, nobody pays him to do that. You said he kept gold coins, jewelry, and silver in that safe. Didn’t anybody ever go looking for it? If it’s really heavy, it couldn’t have gone far.”

A man who owned a big house and held the most land in town was often called, “Squire,” a word the colonists brought with them from Britain. A land baron would be called, “Squire.”

The fierce storm that blew into Old Saybrook in September 1815, and left huge sailing ships in people’s yards, was called a Great Gale; this storm was probably a hurricane, but the word hurricane was not yet in use.

The word hurricane, hurucane, originated with the Taino Native American tribe, the Arawakan-speaking people of Cuba, who lived at the time when Christopher Columbus discovered Cuba, 1492. Hurucane, in Arawakan, meant evil spirit of the wind.