![]() Mabel Osgood Wright

Mabel Osgood Wright

The Mother of Birding in Connecticut

![]()

By Wick Griswold

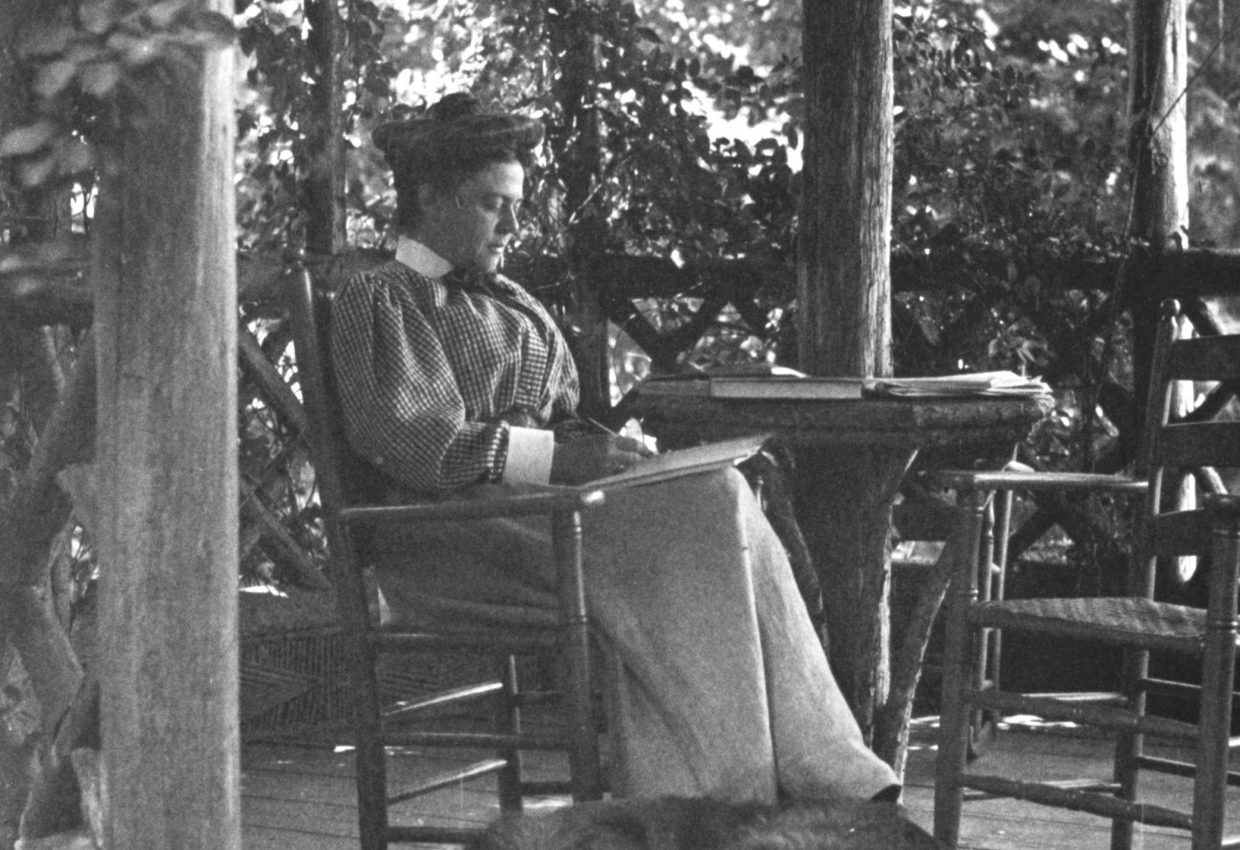

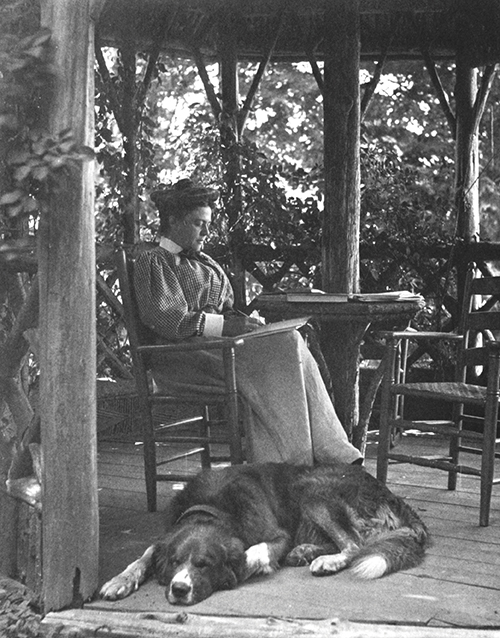

Mabel Osgood Wright photographed by James Osbourne Wright, ca. 1900. Image Credit: James Osborne Wright/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

A remarkable transformation is taking place in the Connecticut River Estuary. Old Lyme’s historic Bee and Thistle Inn is in the process of becoming the “Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center of the Connecticut Audubon Society.” Gracing the banks of the Lieutenant River, it will a play a major role in the promulgation of environmental education, field activities, and advocacy. The new center will serve as a monument to the memory of an extraordinary woman known as the Mother of Birding in Connecticut. It will provide a forum for the continuity and expansion of her innovative ideas, actions, and insights.

That woman is Mabel Osgood Wright, the founder of the Connecticut Audubon Society. Her vast array of accomplishments make her a legend in New England birding circles. Born in 1859, Mabel evolved into a prolific author, photographer, administrator, teacher, lobbyist, birdwatcher, animal rights activist, historian, editor, and wife. The new environmental center will carry on her important, pioneering work using up-to-date methods and methodology.

A native of New York City, Mabel enjoyed a childhood of privilege. Her father was a noted Unitarian Minister. She must have inherited his writing gene (he authored dozens of articles in the important magazines and newspapers of the day). She was educated in private schools and at home. Her heart was set on going to Cornell for medical school, but her father felt that medicine was not a proper discipline for a young lady to pursue. His decision created life-long tension in Mabel between her advocacy of educational and social advancement for women on the one hand, and on the other hand, “careerism,” a path she didn’t think women should follow.

We can only conjecture about conversations teenaged Mabel and Teddy Roosevelt may have enjoyed at the dancing classes they both attended in New York. As they caught their breath over punch after mastering the Quadrille, the nascent naturalists may well have shared their passion and insights about the natural world, and in particular, birds. Very possibly, they shared their mutual interests in the environment and were an inspiration to each other as they danced into their accomplished adulthoods.

A field book of two hundred song, game, and water birds. Image Credit: Smithsonian

Early on, young Mabel published her first newspaper article in the New York Evening Post. This paved the way for her prolific pen to begin pouring forth essays, field guides, novels, and autobiographical work! But she was more than just a writer. She was a dedicated and tireless naturalist who laced up her gaiters to get out in the field and do the hands-on research that made her book, Birdcraft, the first practical guide to the birds of New England and beyond. After the untimely death of her beloved father, she married an antiquarian British book dealer named James Osborn Wright. The young couple moved to Fairfield, Connecticut, where Mabel established her base of operations.

Birdcraft also became the name of the sanctuary that Mabel created near her Connecticut home for her feathered friends. It was one of the first bird-specific educational sites in the United States. She arranged funding from an heiress to the Standard Oil fortune and surrounded the selected area with a cat-proof (so she thought) fence. That enclosure, however, failed to keep felines from feasting on the avians. Also, Mabel hadn’t considered the effects of hundreds of people tramping about the grounds. The eager birdwatchers scared the objects of their interest away. The site was modified accordingly, and in time, Birdcraft became an important venue for environmental education which continues to this day.

The National Audubon Society, which had disbanded shortly after its inception, was resuscitated by Mabel in the form of the Connecticut Audubon Society. Mabel wanted to instill in Nutmeggers an appreciation for all living things, and specific knowledge of our local environment. She served as its President for several years and used it as a platform to advance her advocacy of environmental issues such as opposition to the hunting of birds, particularly heron and egret, for their plumage which wound up on ladies’ hats. She railed against her fellow females for following such a cruel fashion trend she dubbed “feather frenzy” and called out the hunters and milliners who created demand for their products. The plumage industry, of course, excoriated Mabel and her fellow activists as “crazy extremists.”

Mabel was instrumental in the passage of the national Migratory Bird Act. She also initiated the celebration of “Bird Day” throughout Connecticut. In retrospect she can be seen as an early eco-feminist, working to simultaneously change socio-cultural norms about gender roles and the environment.

A plate page of bird illustrations from Birdcraft, 1895. Image Credit: Biodiversity Heritage Library

These themes appear throughout her extensive writings about birding and environmental issues. In addition to her seminal field guide to the birds, she published 25 other books. Many were brought to print under the nom de plume “Barbara.” They were semi-autobiographical in nature. They reflected ongoing musings about the joys of domesticity juxtaposed with inquiries into the rapid changes that the full-blown Industrial Age was wreaking on the social world she was accustomed to, as well as the havoc its pollution wrought on the natural world, particularly rivers.

Mabel also wrote books geared towards children and young adults, and she personally carried her message into Connecticut classrooms. Countless young students learned from Mabel the importance of respecting nature and the joys that can be found by expanding one’s knowledge of wildlife. One of her books in this genre is called Wabeno the Magician, wherein a young person acquires a pair of numinous spectacles that allows her to communicate with the grass, the trees, the birds, and even her dog, Waddles. Its underlying message emphasizes the importance of blending truth with imagination.

The development of the new Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center is a splendid means by which Mabel Osgood Wright’s legacy will continue into the 21st century. According to its executive director, Alisha Milardo, the new facility will “provide up-to-the-minute resources and skills to new generations of students and adults, to fulfill Wright’s vision of active participation in education, research, and advocacy.” As birding and related activities on the river continue to provide a catalyst for deeper understanding and appreciation of the natural world, we can thank the woman whose prolific works still serve as the plinth upon which so much of our information and inspiration rests. Her prodigious efforts may now be manifested in the lives of birds, fish, animals, plants, and people that will be nurtured and sustained in the Connecticut River Estuary for all time.

Renwick (Wick) Griswold is a noted author and Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Hartford. His signature course is the Sociology of the Connecticut River. He is an associate producer of the documentary Ferry Boats of the Connecticut River. He also hosts Connecticut River Drift on iCRV Radio in Ivoryton, CT, and is Commodore of the Connecticut River Drifting Society.