Gillette castle during a fall sunset.

A Man’s Home is

From the deck of the Aunt Polly, William Gillette watched the passing green hills of the lower Connecticut River. It was 1913, he was sixty years old, and he had been thinking about retirement. He anchored the steam-powered houseboat on the eastern shore of the river near the Chester-Hadlyme Ferry. The next morning, he climbed up to the top of the highest of seven hills, beheld the long river spreading out before him, and fell in love. He decided then and there to buy that hill and build his last home there. It was not an idle dream; he was the most famous, and richest, actor in America.

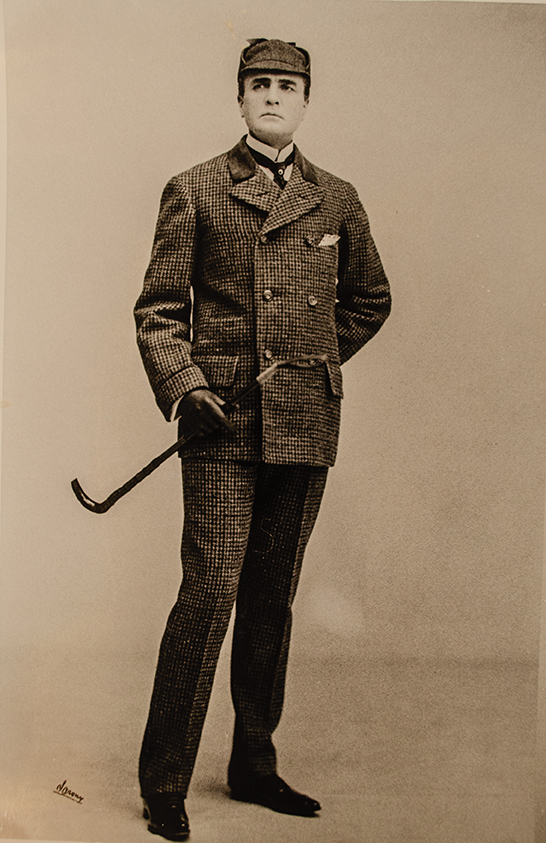

Historical photo Courtesy of Friends of Gillette Castle.

Born in 1853, Gillette spent his childhood upstream on an apple farm along the Park River, in the small Hartford neighborhood known as Nook Farm. His father, Francis, was an abolitionist United States senator and his mother, Elizabeth Hooker, was a descendant of the founder of Connecticut. His aunt was the famous suffragist and spiritualist Isabella Beecher Hooker. His neighbors were the most famous authors in America—Harriet Beecher Stowe and Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain.

Needless to say, Nook Farm created an atmosphere of achievement, of great expectations for young William. He showed promise in mechanical engineering, building small locomotives and designing his own furniture. But what he really liked to do was act. He and his friends put on small plays that the Reverend Joseph Twichell remembered fondly, and he won elocution contests despite being criticized for speaking too “natural” rather than in the high-flown style of the day.

Gillette grew into a tall, slim, and distinguished young man, with an aquiline nose and expressive eyebrows. After graduating from Hartford Public High School, he traveled around Connecticut doing impersonations of actors like Edwin Booth and celebrities like his neighbor Mark Twain. At age 21, he debuted at the Globe Theater in Boston in a play based on Mark Twain’s book The Gilded Age, in a role recommended by the author himself. For six more years he performed in Boston, New York, and as a traveling actor, taking a few classes here and there, but mostly learning on the job. In those lean years, he survived through a small allowance from his father, whom William cared for during a final illness.

Soon, he had starring roles in The Private Secretary and The Professor. While writing and editing the latter, he realized that he could have more freedom, and more money, by doing so. He also began to direct, premiering a Civil War play called Held by the Enemy in 1886. As a writer and director, he pioneered realistic sound effects, lighting, and costumes. Although he did not go as far as his New London neighbor Eugene O’Neill would a generation later, his characters were psychologically real within their dramatic settings, and their dialogue was normal speech rather than overblown poetry. His sets looked nothing like the fairy-tale backdrops of the previous generation’s melodramas.

As an actor, he downplayed emotions rather than exaggerating them, bringing a silken realism to the stage, what he called “psychological acting.” It was an attitude and aesthetic that would eventually become the standard for modern theater. Indeed, Orson Welles later called Gillette the “celebrated American inventor of underacting.” Sometimes he would stand motionless in complete silence, building the anticipation, and when he moved with the slightest gesture—a shrug, a twitch of a hand, an exhaled breath—the audience would explode in emotion. Actress Helen Hayes said of her friend, years later, “There was great simplicity to his style, and style in his simplicity.”

Named after the hill where he sited it on, Gillette called his house “Seventh Sister.”

Meanwhile, Gillette fell in love with and married a woman from Detroit named Helen Nichols and seemed to reach the pinnacle of his life. But she tragically died only six years later after a ruptured appendix. They had no children, and he fell into a deep gloom, taking his first break from the stage. He would never marry again.

In 1894 he returned to the theater in a comedy called Too Much Johnson, and a year later wrote another Civil War play called Secret Service. The protagonist was a Union spy, a character that had never before been portrayed as a romantic hero. The gripping drama was an enormous hit and took him to London, where it brought respect, for the first time, to American plays. It also may have brought Gillette to the attention of a popular English author named Arthur Conan Doyle.

Conan Doyle had just “killed off” his famous detective, Sherlock Holmes, in print. But he did give him one more adventure, writing a play and shopping it around to producers. The script made its way into the hands of Gillette, who read all the Holmes stories and rewrote the play, adding “Elementary, my dear fellow” to the lexicon of the world’s most famous detective, along with the smoking jacket and deerstalker cap. Conan Doyle was enthusiastic and approved the rewritten play, which was a smashing success. For the next 33 years Gillette would play Holmes an astonishing 1,300 times, including in a 1916 silent film, and his smoothness and grace echoed in every future interpretation of the detective of the 20th century.

The 50-by-30-foot Great Hall in Gillette Castle.

As a respite from his worldwide fame, Gillette had launched his 200-ton houseboat, Aunt Polly, in 1900. With a 44-foot-long main cabin, it was decorated with Turkish rugs, white pine woodwork, built-in furniture, a tiled fireplace, and a bar. It was a place for him to escape. But on that fateful day in 1913, on the eastern shore of the Connecticut River, he found an even better escape, a set of rocky hills with a ¾-mile shore front. Hadlyme was rural and not easy to access by curious tourists and celebrity stalkers, but more importantly it was the spot he had dreamed of. Now, he just needed to add a modest home to the sprawling property.

“I’m going to build a rough place to live,” said Gillette. “I don’t know what exactly to call it, but not a house.” Construction began on the “Hadlyme stone heap,” as he first referred to it in 1914, and continued until 1919, costing over a million dollars in the economy of the time. His years of designing stage sets and early promise in mechanical engineering allowed him to plan every detail of the house, as well as an aerial tramway to bring building materials up the cliffs. Often said to be modeled on a Norman chateau or German castle, the 14,000-square-foot steel-framed mansion covered in local field stone really looks like nothing else on earth. Upon first sight, viewers have wildly different reactions, from laughter to wonder, having no real frame of reference to understand it.

The interior, on the other hand, receives more universal admiration. It features 24 rooms of hand-adzed white oak, accessed by 47 hand-carved doors, each with its own puzzle-like latch. The enormous 50-by-30-foot living room with a 19-foot-high ceiling and roaring fireplace could be a stage set, and often was during Gillette’s dinners with friends. A library includes a built-in wall of shelves, and the dining room features a table that glides and locks into place. A secret mechanism unlocked his cocktail bar, while a hidden door allowed him to escape annoying guests. Upstairs an art gallery held over 100 paintings. From the high tower he could see up and down the meandering waterway from East Haddam to Deep River.

The fall view of the Connecticut River from Gillette’s property.

He named the house “Seventh Sister” for the hill it stood on. He loved birdwatching and hiking, and built his own trails and frog ponds on the land. A three-car garage, horse barn, gardener’s cottage, and an 18-inch-gauge railroad were among the delights of the rolling, rocky property. Gillette played engineer on the three-mile train track, while riding behind him were young people from the neighborhood, or the young at heart like Albert Einstein, Charlie Chaplin, and Calvin Coolidge. This “Seventh Sister Shortline Railroad” was where Gillette “took his soul for a ride.”

As his hair turned silver, his eyes and hands remained sharp. From the house he drove his Triumph motorcycle on the winding roads of eastern Connecticut, coattails billowing behind him, the terror of local police officers, whose frequent tickets had no effect on his speed. After he accidentally drove the cycle off the dock at the ferry, a film producer exclaimed that the actor had wasted “$10,000 worth of movie thrills on an audience of five people.” Gillette did not think those small audiences a waste, and during an evening at the castle he created an atmosphere of “awe” and “good humor” for guests. He often put on performances that visitors remembered until their dying days.

He continued to walk the floorboards of real theaters, as well. In 1929, thirty years after his first performance as Holmes, Gillette took the detective role on a farewell tour of America for three seasons. He was celebrated by laborers and leaders alike; actor Booth Tarkington told him, “I would rather see you play Sherlock Holmes than be a child again on Christmas morning.” He kept busy in other ways, too, finding time to write a mystery novel, perform in radio dramas, and invite hundreds of people to his castle, celebrating the living drama of everyday interaction. But soon his age began to show, and he died on April 29, 1937, of a pulmonary hemorrhage. He was buried on the shore of the Farmington River, where his beloved wife had waited for nearly fifty years.

One of the many unique doors and latch mechanisms through the castle.

Saying he didn’t want his dream home, “founded at every point on the solid rock of Connecticut,” to fall into the hands of a “blithering saphead who had no conception of where he is or with what surrounded,” Gillette left the property to his cousin and brother-in-law, but they could not afford to live in it. It went to auction in 1938, but the Depression was on, and the final offer was so low it was rejected. Finally, the Connecticut Forest and Park Association lobbied the state government, and with contributions from both, the estate was saved. It opened to the public as a state park in 1944 and after numerous restorations became one of the most visited places in Connecticut, garnering 350,000 visitors a year.

Gillette’s castle still stands as a living avatar of the man himself, of his intense character and theatricality. It is unique in all the world, a “folly” that worked, an imagination made stony reality. His personality is evident in every unique light switch and crafted window latch. Indeed, in many ways, the castle is William Gillette, an embodiment of the most famous, and most eccentric, American theater actor of all time.

A remaining segment of the train tracks that once spanned Gillette’s property.