Chapter 2: A Post Rider?

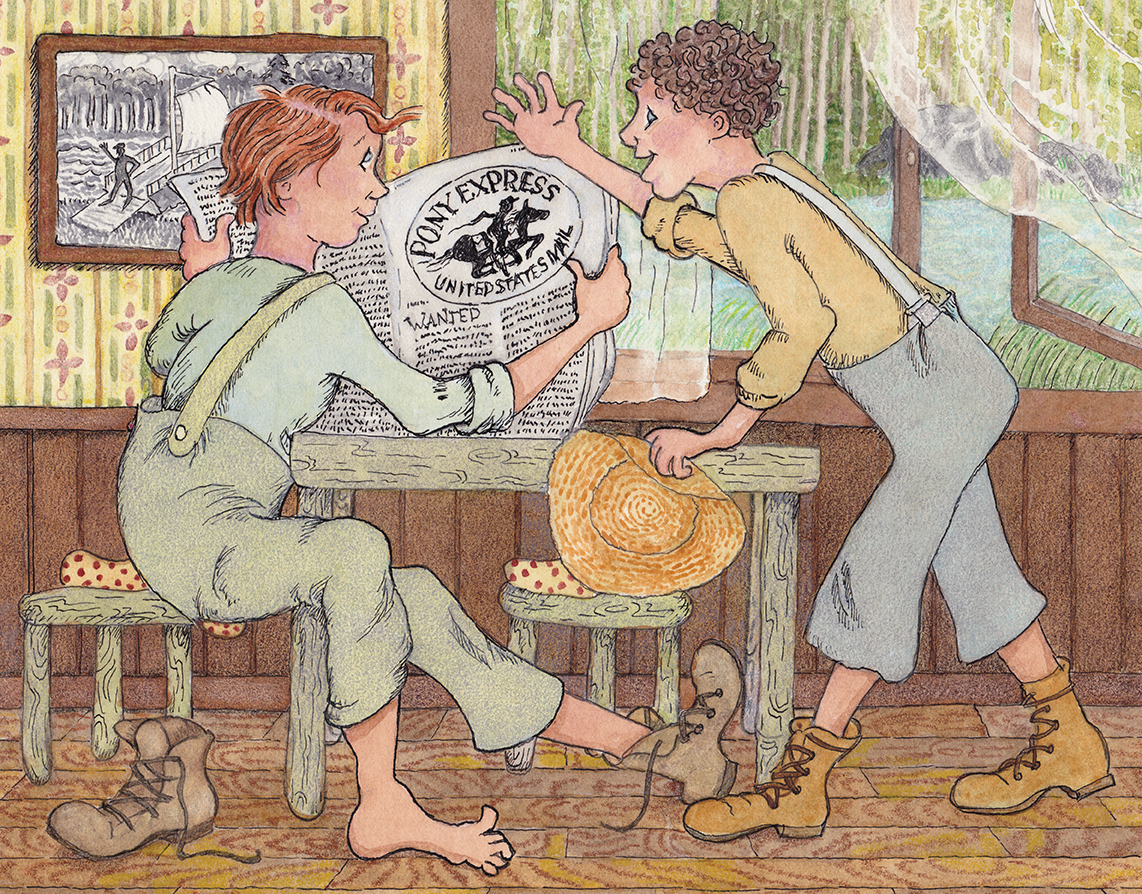

“Hey Ray, listen to this…”

“Not now, JJ; it’s time to ferry the New York mail pouch to Old Lyme.”

“Look. It’s an ad for a company called The Pony Express. They’re looking for riders to sign up now to start next April. Says here, riders will carry a mail pouch from Missouri to California. Can’t you just picture us in San Francisco, Ray? We could go north and look for gold? Listen to this:

‘Starting spring 1860. Wanted. Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over 18. Must be expert riders willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred. Wages $25 per week.’”

“Did you actually listen to what you just read, JJ?”

“Oh spit, Ray, it’s no different than being a post rider.”

Ray held up one hand close to my face, his fingers all spread out; then he folded a finger down every time he made a point. “One—you’re not an expert rider. Two—you’re not a foundling or an orphan. Three—you’re not wiry or skinny.”

“Oh, okay, we can talk about this later. Let me get my other boot on.”

We got to the landing just as the post rider came galloping in on a big chestnut-colored Morgan horse.

“Youse need to get out of the way people,” the post rider shouted as he swung his leg over the neck of the horse, slipped down to the ground, and said, “Who gets the New York mail pouch?”

“That’d be me,” I said, and reached for the pouch. “The Boston post rider is waiting for it in Old Lyme.”

He handed me the pouch, and I handed him the pouch from Boston that he’ll take back to New York.

“JJ! Ray!” Cap yelled up from the ferry. “Got to get going, boys.”

“Just looking at the horse, Cap,” I shouted. “Be there in a minute.”

“Step aside folks,” the post rider said, as he swept a pathway clear with one arm, leading the horse with the other. “Give me and my horse plenty of room.”

“You sure are bossy,” five-year-old Ben said, taking a big step back.

“Sorry, little guy, but my horse got something wrong with his foot, and I didn’t want him to hurt you or anybody else what’s standing too close.”

“We’re not afraid; me and my twin brother, Adam, there, we sat on a horse once, both of us at the same time, and a man took our picture.”

While the post rider was talking to the twins, their sister, Clara, was behind him looking up at that huge animal when pretty soon that horse bows down his head and touches his nose to hers like they’re old friends. She strokes his nose so gentle you’d think he was a kitten.

“You sure got a natural way with creatures, little sister,” the post rider said. “Will you fetch a little bit of water for me, please?”

“I will,” Clara said. She ran to the table, grabbed a tin cup, and filled it with water from the rain barrel.

“I will,” Clara said. She ran to the table, grabbed a tin cup, and filled it with water from the rain barrel.

“Why do you call Clara ‘little sister’? She’s my big sister,” Ben said. “She’s six. How old are you?”

“I’m sixteen,” the post rider said, “but I feel like I’m ninety.”

Ray elbows me hard in the ribs and whispers, “See? Being a post rider makes you old before your time.”

Clara handed the cup of water to the post rider and said, “Can I watch how you fix his foot? You probably didn’t know this, but I doctor birds.”

“Very interesting, little sister. Sure, you can watch.”

He gently lifted the horses’ left front hoof, bent it back, and braced it between his knees, “Let’s take a look at the bottom of his hoof. This here’s a fresh horse, got no more than ten miles on him.”

“You mean this isn’t your horse from home? Clara said.

“I don’t have a horse of my own. I get a fresh horse every ten to fifteen miles between New York and here.”

Then he laughed, but it’s not really funny, what he said. “Mail service puts a higher value on a horse than on us riders; they expect a rider to ride hard and fast all day, but the horse is treated like a king.”

While he talked, he dug mud and small stones out from the bottom of the hoof with a pick.

“Can I try that part?” Clara says, “I’ll be gentle. I had a splinter in my foot last summer, and I remember how much it hurt.”

“Okay, little sister, you can help; your little fingers might be better than this old pick.”

She scooped a little water from the cup and gently rubbed it into the bottom of the horses hoof, in the center of the horseshoe, washing away more mud. Next thing I know, she’s digging her finger down and all around, then slipped it under something. She worked it out, rinsed it in the cup and handed it to the post rider. It was a stone with lots of sharp edges.

“Good job, little bird doctor,” he said. “That would have caused a painful bone bruise.”

“JJ! Ray!” Cap shouts from the dock, “Wind’s up we’ve got to go—now!

“On the way, Cap.”

I toss the New York mail pouch to Cap, and he stashes it in the Post Office box on the ferry. Cap unfurls the sail, which was flopping this way and that like wet laundry on a line, then all at once, the sail captured the wind and, like cheeks puffed out ready to blow out a candle, took shape with a mighty—Pop!—Ray and I leapt off the grassy bank and onto the ferry as it moved away from the dock. I raised the anchor, we lifted the ramp, and off we sailed, into the open water of the Connecticut River.

“Looks like it’s going to be a fun ride for sure,” I said.

“Look!” Ray shouted, pointing to an osprey flying overhead with a menhaden in his talons. “Breakfast for the family.”

“Cap turned his back to the wind, cupped one hand around the bowl of his pipe lit the tobacco, and said, “Tell me what you see, boys.”

“A lot of chop,” Ray said, “wind, offshore, from the north.”

“And? JJ? What do you see, son?”

“Skyward I see altocumulus clouds that promise thunderstorms later today. Down here I see a fast current in the river that we’ve got to get across. Can’t sail down river direct to the landing at Old Lyme, too risky; we wouldn’t be able to stop.”

“Yeah,” Ray laughs. “If we got in that current, we’d get carried straight to the mouth of the river and spit out into Long Island Sound, where we’d never be seen or heard from again.”

“So, JJ. What’s your plan?” Cap said.

That’s Cap’s way of telling me I’m the captain today and he’s not going to lift a finger. We’re bouncing around on the choppy water, a few whitecaps were showing up, which meant the wind was about 15 knots.

“Like Squire says, best to follow a ferry angle upriver, then keep close to the bank and cruise the half-mile or so downriver to the landing at Old Lyme.”

Cap smiled, closed his eyes, nodded, and took another whiff of his pipe.

“Admit it, JJ,” Ray shouted over the wind as we adjusted the sail and cut across the chop and the current, “You’re no post rider; you’re a mariner at heart. It’s in your blood, like your father, there, his father, and all the other JJs that came before you, and you don’t have to be an orphan, thin as a marsh reed and ‘risk death daily,’ to do it.”

Teenagers played a major role as essential workers in the late 18th and early 19th century systems of mail delivery. These youngsters were expected to be expert horsemen or mariners and were among the first to ride the southern route between Boston and New York. The Old Saybrook ferry served as a major link in the Boston Post Road.

Although stories of the Pony Express always include the text of the ad quoted, there is no evidence the ad ever actually appeared.