Searching for

Grouse

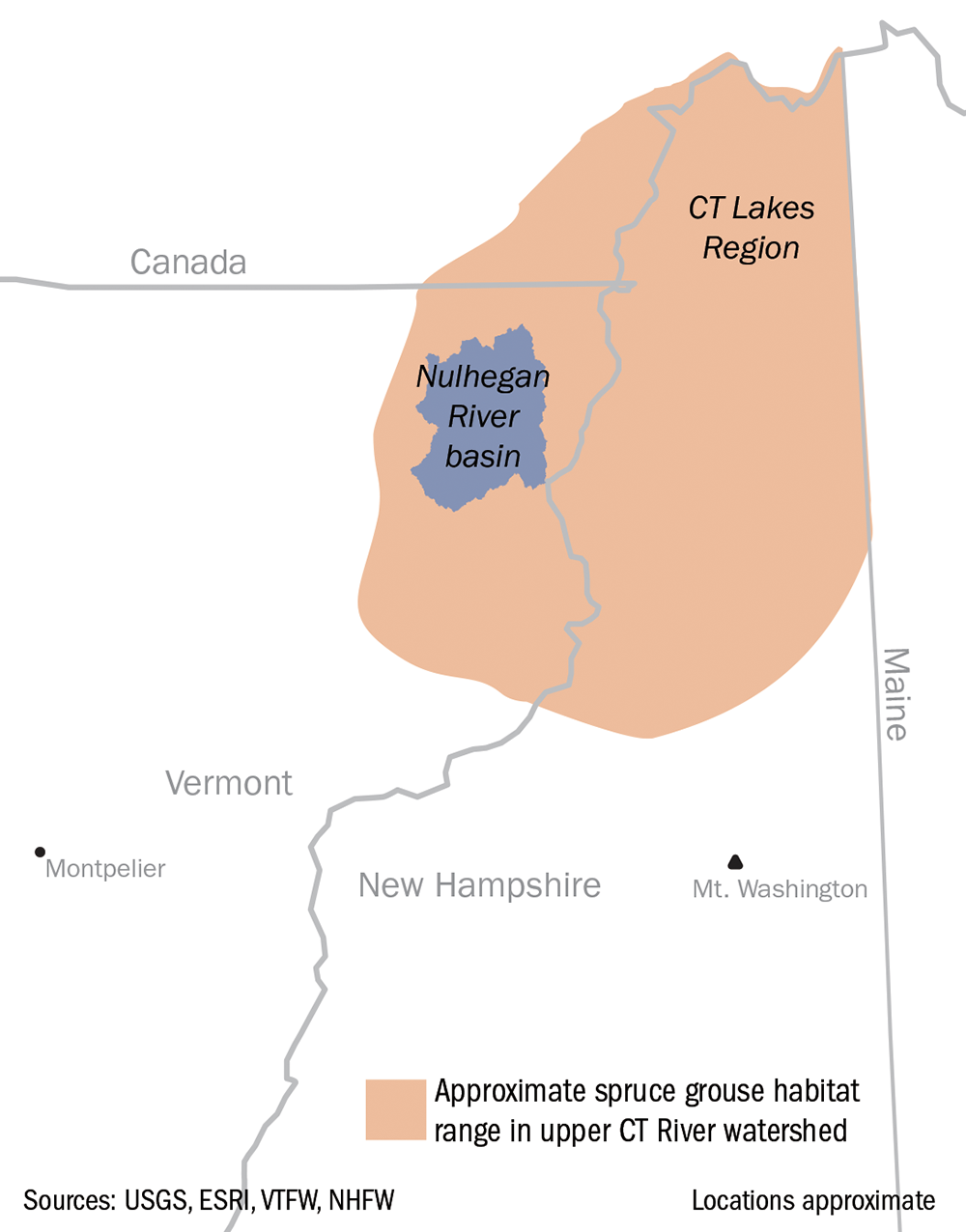

A limited population of spruce grouse make their home in the northern reaches of the Connecticut River watershed. What is being done to protect the southernmost limits of their habitat range?

What a striking bird against the boreal forest greenery. His black breast feathers dipped in pearl white. His back vermiculated with petite black and white stripes that accented the contrast with his mottled brown wings lying flat against his body. But those eyebrows! Fully engorged and so brilliantly red they surely couldn’t be real. But of course, they were real. As real as the day is long.

Searching for Spruce Grouse

“Be sure to listen for the flutter flight.”

That was the final reminder to me as I was dropped off in the middle of the 24-square-mile Nulhegan River basin in Essex County, Vermont. That was the last human I would see for the next several hours—longer if my orienteering skills failed me. Essex County is the most sparsely populated region of Vermont.

I was there to conduct my first spruce grouse breeding bird survey. It was cold. It was during the first two weeks of May, but freezing temperatures at sunrise are the norm.

The 30 observation points of my survey route represented the shape of an out-and-back trapezoid. Meaning, if all went well, I would end up somewhere near the starting point. Time would tell. With map, compass, and tape player in hand, I began to pace off the first 100 meters to the first point.

The basin, then part of International Paper Company lands, was laced with a network of skidder trails that connected to log landings and main haul roads. Given all those landmarks, it would seem difficult to get lost. However, once off the road, one was immediately immersed in a tangle of blow-down and impenetrable alder swales and dog-hair conifer saplings.

Female spruce grouse, Nulhegan River basin, Vermont.

Adding to the challenge was the fact that the topography was generally flat with only a hummock or granite boulder to gain any elevation for perspective. Long before GPS and cell phones, surveys such as these relied on a dependable compass and an accurate map, without which one could literally walk in circles for hours.

In the landscape of tangled trees and shrubs competing for sunlight and soil nutrients, one of the first and most memorable experiences is being engulfed by the intense fragrance of all those spruce and fir trees. It is as though one were standing among 100 Christmas trees all bunched together.

Upon arrival at my observation point, I checked my watch and noted the time, 5:30 a.m. I engaged the tape player, set it down, and began to watch and listen. As the recording played a continuous loop of an aggravated hen call, I periodically checked the time to be sure I stayed within the three-minute observation period. Spruce grouse are not especially vocal like some birds. But, during the breeding season, males will readily respond to the female’s aggravation.

As my observation time elapsed, I shut the player off and recorded zero grouse seen or heard. I took just a moment to listen to and appreciate the deafening silence of these big woods. The second stop revealed no grouse either, but I was treated to a flock of boreal chickadees as they zoomed and fluttered about me for an ever-so-brief moment.

I stopped the player after my tenth stop and again recorded no grouse. As I picked my head up from the recording paper, I was startled to see a Cooper’s hawk perched in a black spruce just 10 meters away. As marveled as I was to see such a magnificent creature, I was also very disappointed. If there were any spruce grouse in here, they were long gone by now. The good news, though, was if a savvy predator could be deceived by the recording, so could a spruce grouse.

As I arrived at point number 21, there was an all too familiar combination of trees, shrubs, and moss-covered ground as with the previous points. Except, there seemed to be more space between the trees and less woody material covering the ground. Subtle but maybe meaningful. Three minutes again passed, and I turned the play-back off. Silence. But only for a moment.

Then came what sounded like the soft flutter of wing beats. I turned and, to my surprise, saw a male spruce grouse striding determinedly in my direction. I froze. My eyes glued to his every movement, fearful that any sort of movement from me, even a blink, would scare off the prize of the day. He got to within 10 feet of me when he realized his mistake and casually flew about 15 feet up into a white spruce tree. There we were, staring at each other face to face. Him with the curiosity attributed to the “Fool Hen” and me in total and utter astonishment!

While still transfixed, as if to reward my hard work (and a bit of beginner’s luck thrown in), a second beat of wings and a second male grouse landed in a spruce tree at three o’clock to the first male. Just as I raised my Pentax MX single lens reflex camera loaded with a roll of Kodachrome 64 film, my beginner’s luck expired, and the birds, as if having conspired in advance, flew out of sight. A priceless moment winged away.

The remaining points did not reveal any more grouse, only the distinctive pecking of a black-back woodpecker at the final stop of my survey. But I wasn’t disappointed in the least. Simply having been a part of the boreal forest, if for only a day, would have been gratifying enough. Having seen and recorded the two male spruce grouse made the whole experience complete.

To add to the day’s high, and to a bit of surprise, I found myself on the main haul road within a hundred meters of where I should have exited the woods.

The Spruce Grouse

Also known as the Canada grouse, the spruce grouse (Falcipennis canadensis) is found throughout North America where its boreal forest habitat of middle-aged balsam fir and white or black spruce is abundant. This type of forest is found in the northern latitudes and has adapted for the colder climate. However, at the very southern edge of the grouse’s range, habitat is limited to portions of the Great Lake states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota; the Rocky Mountains of Washington, Idaho, and Montana; the Adirondacks of New York; and northern New England. With respect to the Connecticut River watershed, habitat is limited to the bottomland conifers of the Nulhegan River basin and the boreal forests of the Connecticut Lakes drainage in Coos County, New Hampshire.

Spruce grouse are well-defined by their feeding preferences of the needles of their coniferous habitat, namely spruce, fir, and pine. To digest this winter roughage, the bird’s crop and intestinal system undergo an expansion. By doing so, additional space and time are created to break down the nutritional components of their dietary staple. Come spring and summer, grouse can also be found consuming early season berries and insects as it forages grassy forest openings and old abandoned beaver colonies. This habitat is especially important for newborn chicks to consume much needed protein for their proper development.

The Boreal Songbird Initiative estimates that 87% of the continental spruce grouse population reside in Canada where it is managed as a common game bird throughout the country’s provinces. The majority of the remaining 13% can be found in Alaska where it is also listed as a game bird. In the lower 48 states, only in Minnesota are spruce grouse listed as a game species. While well populated in Canada, the spruce grouse’s habitat range only slightly dips south into the United States. On that southern edge of their habitat range, they are listed as threatened in Wisconsin, a species of special concern in Michigan, New Hampshire, and Maine. Only in New York and Vermont are the respective populations so imperiled they are designated as endangered.

Prior to European arrival in North America, spruce grouse were likely more common in New York and New England when the boreal and coniferous forests were far more connected to their Canadian base. The New Hampshire Fish and Game Department’s 2015 Wildlife Action Plan reported that spruce grouse were once common in the state at the time of the colony’s settlement in the early 18th century, but by 1880, they were seldom seen.

With much of the boreal forest habitat within the Connecticut River watershed reduced to relatively small and disconnected patches, edge-of-range spruce grouse face an uncertain future. Natural events such as windstorms, spruce budworm outbreaks, and human timber harvests can exert short-term habitat losses, which place even greater pressure on remaining habitat to support the grouse population. But the long-term impact from climate change, however, is likely to be more profound. As warming conditions become more prevalent, growing conditions become more suitable to deciduous tree species and less so for the boreal species. If model projections are correct, in time there will be whole forest conversions that do not favor the spruce grouse.

Map by Christopher Zajac.

Of the threats to the future of New Hampshire’s spruce grouse population, the Fish and Game Wildlife Action Plan identifies the three most serious to be climate change induced spruce-fir retraction and forest structure altered by insect outbreaks or over-aggressive timber harvests.

New Hampshire Fish and Game biologist Jillian Kilburn has observed a “slight uptick” in grouse numbers during the last 10 years while conducting winter wildlife surveys of Coos County. That observation may be attributed to over 180,000 acres of conserved land properties contributing to spruce grouse habitat that include: The Connecticut Lakes Natural Area (25,000 acres), Connecticut Lakes Timber Company (146,392 acres), the Vicki Bunnell Preserve (10,330 acres), the Nash Stream State Forest (39,601 acres), and portions of the western slopes of the White Mountain National Forest.

For Vermont’s remaining spruce grouse, the future may be bleaker. In the Green Mountain State, they are truly living at the edge of their edge. That is the view shared by Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department biologist Doug Morin. “With only one isolated population and a habitat that’s at the southern edge of its range, it’s hard to imagine them persisting in Vermont for decades/centuries to come.”

Listed as a Vermont endangered species since 1988, the greatest single factor weighing against them is the lack of extensive suitable and contiguous habitat. There are an estimated 16,000 acres of spruce grouse habitat, all of which is within the Nulhegan River basin of Essex County. Although those acres are conserved by the Silvio O. Conte National Wildlife Refuge, the state Wenlock Crossing Wildlife Management Area, and Plumb Creek Timber Company, the conserved lands still only amount to less than a tenth of the habitat found in neighboring New Hampshire.

Tri-annual spruce grouse surveys of the Nulhegan River basin since 1988, conducted by Vermont Fish and Wildlife biologists, suggest a population estimate of between 100 to 300 birds. Any trends that can be identified from the data don’t indicate a corresponding “uptick” in grouse numbers on the west side of the Connecticut River.

Tri-annual spruce grouse surveys of the Nulhegan River basin since 1988, conducted by Vermont Fish and Wildlife biologists, suggest a population estimate of between 100 to 300 birds. Any trends that can be identified from the data don’t indicate a corresponding “uptick” in grouse numbers on the west side of the Connecticut River.

The best time to observe spruce grouse during their courtship occurs when only a few patches of the winter’s snowfall remain. For the Nulhegan River basin, this meant sometime during the first two weeks of May.

The future of spruce grouse populations at the edge of their range in the upper Connecticut River watershed will remain uncertain as short- and long-term threats mounting against the species persist. But hope should not be cast aside. Efforts by New Hampshire and Vermont wildlife officials and conservation organizations to conserve their boreal habitat will go a long way to buffer the near-term impacts.

Every species on the planet is remarkable in its own way and so too is the spruce grouse. For the last 10,000 years, they have made their living in the severity of what the boreal forest has plied against them. The resilience of those specialists that have endured the severity of that environment will be borne out if human efforts to arrest the damaging impacts of climate change prevail.

John Buck is a retired wildlife biologist living in Waterbury Center, Vermont, with his wife, Cathy. When not writing, John’s days are filled managing their 70-acre family maple farm.

Daniel Berna is a wildlife photographer based in Newbury, Vermont. This is his second photography feature for Estuary. More of his work can be found at danielberna.com or his Instagram account @danielberna5462.

Male spruce grouse, Nulhegan River basin, Vermont.