VENTURE

SMITH’S

LONG STRUGGLE

Spring on the Venture Smith Homestead. Acrylic on canvas. 2010. Venture Smith’s 130-acre homestead on Haddam Neck in East Haddam, CT, is portrayed by artist Maggie Arnold based on evidence uncovered during archaeological surveys.

In 1776, at the dawn of the American Revolution, Venture Smith stood on the banks of the Connecticut River a free man. He had his own farm, his wife and child lived with him, and he had a prosperous 130-acre farm in the village of East Haddam. It had taken him a long time to get there, and the journey was not of his own choosing.

Born in Dukandarra, West Africa, in 1729, Broteer Furro was taken as a prisoner of war at age six. He described the experience six decades later with disturbing precision:

They then came to us in the reeds, and the very first salute I had from them was a violent blow on the head with the fore part of a gun, and at the same time a grasp round the neck. I then had a

rope put about my neck, as had all the women in the thicket with me, and were immediately led to my father, who was likewise pinioned and haltered for leading.

Eventually sold to a European slave ship in Ghana, Broteer survived a smallpox outbreak on board and was bought by an American colonist named Robert Mumford “for four gallons of rum, and a piece of calico.” This man gave him the new name “Venture” for the “business venture” he was embarking on.

Image Credit: Public Domain/Academic Affairs Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

In 1737, Venture was enslaved on Fisher’s Island off the New London coast. At the time, one in five people at the eastern end of Long Island Sound were of African descent, and slavery was legal in both Connecticut and New York. For nearly two decades, Mumford used Venture’s labor to help run the 3,000-acre sheep and dairy farm on the island. He was trustworthy and faithful to Mumford, but the man’s son tormented him, tying him up and whipping him.

While on the island, Venture married a fellow slave named Meg and, in 1754, attempted to escape his bondage. Convinced by an Irish indentured servant named Heddy, three slaves including Smith made it to Montauk Point on Long Island before discovering that the man’s true intention was to steal their belongings. Smith and the other two slaves hunted Heddy down and brought him back to Fisher’s Island. The servant was put in jail, and the slaves were put back to work.

That same year, Venture and Meg had a daughter named Hannah. But the family was separated when he was sold to Thomas Stanton of Stonington, Connecticut. They were reunited the following year when Stanton bought Meg and Hannah, but this near disaster demonstrated how tenuous family life was under slavery. Despite these obstacles, Venture and Meg had two more sons while living in Connecticut.

Stanton was a brutal master who beat Venture with a boat oar and stole the money he and Meg had been saving to purchase their freedom. The situation became untenable when Stanton and his brother tried to beat him up again, and Venture fought them off. In this colony, at least, they couldn’t simply kill him outright, and so they sold him again.

His final owner, a Stonington merchant named Oliver Smith, allowed him to work extra to earn his freedom. Later, this practice would become less common, but in 18th century New England, it was possible, though dependent on the whims of the owner. In 1765, Venture bought his way out at the high price of 71 pounds and 2 shillings. As he said, though, “My freedom is a privilege which nothing else can equal.” He took his surname from Smith, in gratitude for what he saw as the man’s “generosity.”

Venture then set out to buy Meg and their two sons from Thomas Stanton, and their daughter from Mumford. Now a free man, he worked on a whaling ship, cut cordwood in vast quantities, and invested in land. In 1770, he bought 26 acres near what is today the Barn Island Wildlife Management Area (in Pawcatuck, CT) and five years later sold that land at a profit, using the money to buy land on Haddam Neck. He bought more and more land, eventually gathering 130 acres along the Connecticut River. He never bought new clothes, never attended gatherings with his “mates,” and never spent excessive money on “spirits.” Though he was often cheated in transactions, he was also treated with respect by other members of the local community. He eventually bought his sons’ freedom for 200 dollars each.

Venture then set out to buy Meg and their two sons from Thomas Stanton, and their daughter from Mumford. Now a free man, he worked on a whaling ship, cut cordwood in vast quantities, and invested in land. In 1770, he bought 26 acres near what is today the Barn Island Wildlife Management Area (in Pawcatuck, CT) and five years later sold that land at a profit, using the money to buy land on Haddam Neck. He bought more and more land, eventually gathering 130 acres along the Connecticut River. He never bought new clothes, never attended gatherings with his “mates,” and never spent excessive money on “spirits.” Though he was often cheated in transactions, he was also treated with respect by other members of the local community. He eventually bought his sons’ freedom for 200 dollars each.

In one incident, Venture was prosecuted for losing a cargo of molasses overboard in Saybrook, even though he was not even present at the time. “Captain Hart was a white gentleman and I a poor African,” he wrote later wryly. “Therefore, it was all right, and good enough for the black dog.” Complicating the story was the fact that Smith himself purchased a number of his own slaves to work the land in East Haddam. At least three ran away, one after stealing forty pounds. Another preferred to work for his former master, and Venture had to let him return, losing 400 dollars in the process. The embedded inequality of a society part slave and part free made for an ethically compromised world, and Venture was just as affected by this system as anyone else.

Image Credit: Eric D. Lehman

Sorrows continued to beset his life. His eldest son, Solomon, went on a whaling expedition and never returned. His daughter died of a strange illness after being neglected by her husband. Nevertheless, he kept working, retaining good habits and “good character.” What gave him the most joy in his difficult life was his reputation for “truth and integrity,” and no matter how many times he was cheated, he refused to do the same to others.

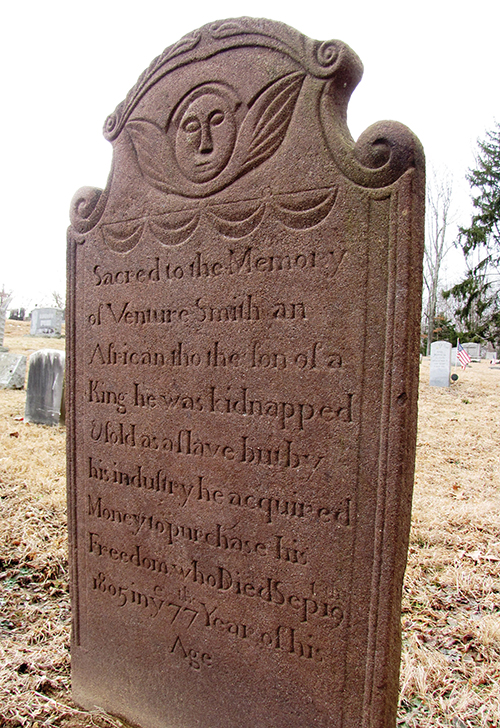

At age 69, going blind, “bowed down with age and hardship,” he wrote one of only a dozen first-hand accounts of American slaves taken directly from Africa, A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture Smith. He died a few years later in 1805, a rich landowner who had worked his entire life for the freedom of himself and his family. He was buried just uphill from the River at East Haddam’s First Church of Christ, today an essential stop on the Connecticut Freedom Trail.

His farm site on Haddam Neck was occupied in the 20th century by the Connecticut Yankee Nuclear Power Plant. Recent archaeological excavations unearthed the remains of house, barn, blacksmith shop, and dry dock on the property. Someday, perhaps, all those who treasure freedom will be able to walk along the River on that old farm, and think about how far we have come, and how far we still have to go. Venture Smith did it all in one lifetime.

About the Artist

Maggie Arnold has lived and painted in Maine for over 40 years. She spent seven years living in coastal Connecticut where she met the archaeologist who was working at the Venture Smith Homestead site. Venture’s story inspired Maggie to donate her time and talent to create a depiction of a day in the life of Venture and his family. Maggie earned a BFA degree in Art Education from Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA. She taught art in public schools in Westerly, RI, and Monmouth, ME. Her paintings are often inspired by the hard-edge pop art style of the 1960s.