On the west shore of the Connecticut River, the town of Hartford bustled in the morning light. People gathered at the market on the town green, in taverns, and in coffeehouses, where a few years earlier the local secret society might have planned a revolution, spurred on by the demon caffeine. Now, in the 1780s, you might find a group of recent college graduates in their place, sitting in ladder-back chairs at a long table talking about literature, about how to build a new nation with words.

On a good day, you might see John Trumbull, the cousin to the governor, talking with firebrand Joel Barlow and Timothy Dwight visiting from Fairfield. Nearby is Trumbull’s young roommate, Noah Webster, chatting with Richard Alsop and Lemuel Hopkins about replacing the old English spelling book with a new American version. They are joined by others, sharing a plate of chestnuts, a pot of coffee, and vigorous opinions. This is how a literary movement is born.

The most prominent member of this literary crew, John Trumbull, was born in 1750 in Watertown, Connecticut, and passed a college entrance exam at age seven. By thirteen he had learned Greek and was off to Yale College, where he squeezed into Old College Hall with rowdies from other towns and colonies. Two years later in 1765, he made a good friend in Timothy Dwight, the grandson of preacher Jonathan Edwards. Dwight was studious and healthy, with a voice like melting honey and a mind that could memorize long poems with little effort. He rigorously controlled every piece of food that went into his body, tried vegetarianism, and eventually had to recover from an eating disorder. His extensive reading led him to need large horn-rimmed glasses.

They were diligent students but active against the Stamp Acts and the oppressive administration at Yale. They also had to learn poetry on their own since college students in those days had no literature (or science) classes. They raided the Yale Library and bought books at Benedict Arnold’s nearby bookstore. Soon they were joined by David Humphreys of Derby, who entered school in 1767 at the old age of fifteen. He joined a secret literary society with Dwight and Trumbull, who gave the commencement oration that year. Humphreys and Dwight stayed at Yale as tutors, instructing younger students like Nathan Hale and Benjamin Tallmadge.

Trumbull had the first major publication from these “Wits,” called “Progress of Dulness,” a send-up of college life that followed the adventures of “Tom Brainless” and “Harriet Simper” through a mind-numbing educational process. “Four years of college dozed away/In sleep, in slothfulness and play,/Too dull for vice, with clearest conscience/Charged with no fault but that of nonsense.” Soon afterwards, Trumbull got a job in the Boston offices of a lawyer named John Adams, but the chaos surrounding the Tea Party drove him back to Connecticut.

Another younger boy named Joel Barlow transferred from Dartmouth to join them at Yale. Originally from Redding, Connecticut, he was tall and handsome, easily making friends with the older literary crowd and his classmate Noah Webster. Barlow wrote to Webster, saying, “let us show the world a few more examples of men standing upon their own merit, and rising in spite of opposition.” It was not just literature they were interested in but progress and revolution.

That next year, students took part in revolutionary protests, and the Battles of Lexington and Concord threw the spring semester into chaos. Humphreys and Barlow both joined the Continental Army, and Dwight became an army chaplain. Their friend Nathan Hale soon found himself at the end of a hangman’s noose, paraphrasing a play he had learned in their literary society, Addison’s Cato: “I only regret I have but one life to lose for my country.”

Trumbull turned his pen to the war effort, writing M’Fingal, a mock epic that brought the war down to the size of a New England town meeting and an argument between loyalist Squire M’Fingal and the revolutionaries. It was not just propaganda, though, and the patriots themselves did not escape his satire. That balance would make this poem the only one by the Wits to survive in schoolbooks and public imagination well into the 19th century.

The rest continued to write but focused on their service to the army, and to the new country. Humphreys became a colonel and presented the surrendered British banner to the Congress. Barlow briefly became a minister, as well as an editor, storekeeper, and lawyer in Hartford, partly to be near to Trumbull. Barlow also finished The Vision of Columbus, the first work of poetry to connect the Anglo-American experience with the Italian explorer. Another friend, Dr. Lemuel Hopkins, joined them, and the three friends revised the Christian Psalm book, removing mentions of both “King” and “England.” Timothy Dwight’s nephew-in-law, Richard Alsop, moved upriver from Middletown and opened a bookstore where they often gathered. Trumbull and Barlow were elected to the Hartford Common Council, David Humphreys was elected to the state legislature, and now everyone but Dwight lived on the banks of the Connecticut River.

Dwight had accepted the pastorate of Greenfield, Connecticut, and wrote The Conquest of Canaan, an epic in heroic couplets that connected the Old Testament to the founding of America. He may have missed the creation of a mock epic written collectively by the others, The Anarchiad, though he may have simply kept his name out due to his position as minister. It was a plea for a stronger central government to balance the chaos that sometimes comes from unfettered democracy, or “mob rule.” The cause of these “Hartford Wits” had shifted from revolution to the unification of the states.

That project was helped immeasurably by the young, red-haired Noah Webster, who had grown up in West Hartford, gone to Yale with Barlow, and lived with Trumbull in Hartford twice during the 1780s. He was the first and only Wit to become a best-selling writer, though not for poetry. He created a spelling textbook that would be used by every child in America for the next 75 years. Many decades later, he would also finish the first comprehensive American dictionary, part of his lifelong project to culturally unite America.

The rest joined him, for a while. Humphreys wrote the classic hagiography, Life of Israel Putnam, attempting to define national character. Dwight published Greenfield Hill, a long poem dedicated to the simple values of rural America. In addition to preaching, Dwight taught at Greenfield Academy, and one of his students, Elihu Hubbard Smith, moved to Wethersfield and joined the Hartford Wits. He edited American Poems, Selected and Original, published in 1793, which included poems by Trumbull, Humphreys, Dwight, Barlow, Alsop, Hopkins, and others. It was the first general collection of poetry ever attempted in America.

And yet, a century later, the Wits would be largely forgotten, thought to be “unreadable,” and embarrassing examples of “epic pomp.” This is fairly common for literary movements, and the second one in American history, the Knickerbocker Group from New York, has not fared much better. Not until the Concord Group of Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, and Alcott does “American Literature” begin for most readers, teachers, and anthologies.

Part of this is the fault of critics, who too often focus on their own aesthetic tastes and not on historicity. But part is due to the Wits themselves, who refused to “live in a musty attic” for the sake of literature alone. Dwight found time to write here and there, but mostly spent his time as president of Yale and professor of theology. Trumbull served as a Connecticut Superior Court judge, stopping all his verse due to his belief that “the character of a partisan and political writer was inconsistent with the station.” Humphreys brought merino wool sheep to the country and served as ambassador and “secret agent” for Washington and Adams. Barlow tried to found a national university and served as ambassador under Adams, Jefferson, and Madison, dying while trying to meet with Napoleon on his retreat from Russia.

Though they remain footnotes in the great pageant of American literary history, Joel Barlow, John Trumbull, Timothy Dwight, David Humphreys, and their friends helped define the national mythology that often leaves them out. Their work reflected the most important theme of their age: the potential and risk of our democratic experiment. Often, they failed to reach the heights of their contemporaries in Europe, and often they failed to find readers in their own country. Being the first to do something, and also being the best at it, is a difficult thing to accomplish.

That task was made more difficult by the Wits’ true loyalty—to improving the community, to what we might call the best part of politics. Their belief that the Revolution would usher in a golden age, and that they could play a part in it, seems too idealistic for more cynical times. And yet, we still hang on to that naiveté, continuing generation after generation in that most American of traditions—hope.

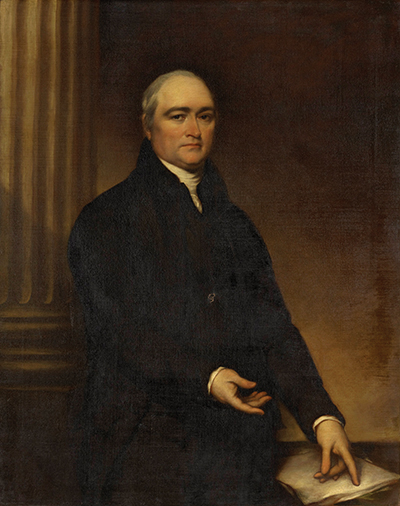

From Top: Timothy Dwight, Painting by John Trumbull 1817, Yale University Art Gallery

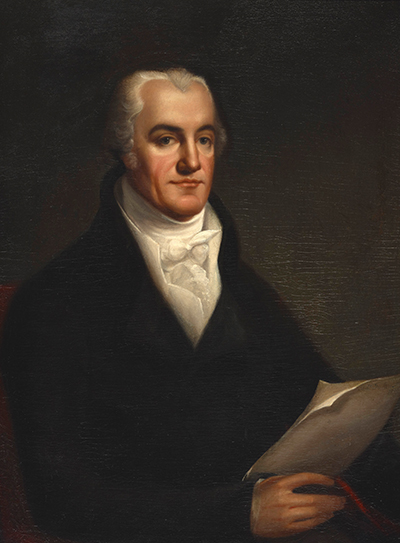

Joel Barlow, Painting by Robert Fulton 1805, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields

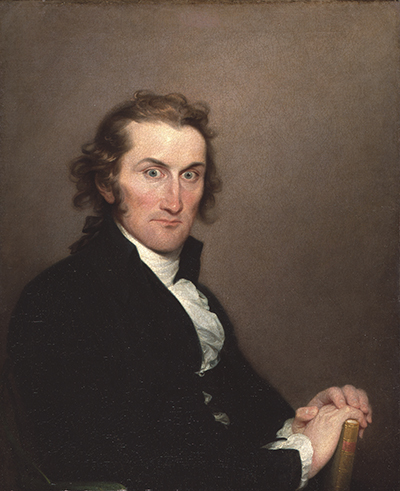

Lemuel Hopkins, Painting by John Trumbull 1793, Yale University Art Gallery

John Trumbull, Painting by John Trumbull 1793, Detroit Institute of Arts Collection

David Humphreys, Painting by Gilbert Stuart ca. 1808, Yale University Art Gallery

Noah Webster, Painting by James Herring 1833, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution