Moose

Moose comes from the Algonquin word Mooswa, meaning “the one who strips twigs.” To fulfill its life functions, the North American moose, Alces alces, requires some 10,000 calories per day, equating to between 50 and 100 pounds of food. But the large cow moose I saw deep in the woods of northern Vermont wasn’t feeding. She was running straight at me.

It was a warm November day, unusual for deer season in Vermont. Given the temperature, I was still-hunting even slower than usual, and it seemed like a good time to enjoy my apple and 3-decker peanut butter sandwich. Scaling the Volkswagen-sized granite boulder in front of me led to the perfect lunch seat. Sitting in sight of the 2,766-foot Wheelock Mountain, in awe of my surroundings, made my day whether I saw a deer or not. For those seeking solitude, this is the place to find it, west of the upper reaches of the Connecticut River in the beautiful Northeast Kingdom. Around me were 20,000 acres of unbroken forestland—mixed hardwoods mostly, with scattered red and white spruce and balsam. Hobblebush and striped maple comprise the understory, with the usual glacial debris of big boulders scattered about. The stubborn leaves of a few maples glistened from a recent rain.

A bull moose wanders through the woods of Sugar Hill, New Hampshire, in early fall.

Image Credits: Getty Image/UfimtsevaV (moose family). Duane Cross (moose photo).

The trembling ground was mild but discernable. I probably would have dismissed it except that it continued and seemed out of place. Earthquakes are rare is these parts of the Appalachian chain, and a sonic boom is just as unlikely. Being miles from any villages or roads, I ruled out a backfire or other traffic noise. Over my left shoulder came the sound of branches snapping. Twisting in that direction, I saw the bulky silhouette of an animal running towards me. In my experience, moose come in two sizes—big and bigger. This moose was in the former category—still, the 700-pound cow was twenty-five yards away and closing on me quickly. I didn’t have time to decide by a coin toss between fight or flight. And yet, something in the look of her eyes told me I was in no danger. The cow moose was not running at me but fleeing some other pursuer. Sure enough, maybe ten yards from me, she veered to my left and continued her gallop into the expanse of the forest. Before I could make sense of what happened, a calf, perhaps four months old, on awkward, spindly legs came galloping after its mother. Already this little moose understood the Game of Life. What had impelled the normally slow and deliberate moose to run for her life and that of her calf? Coyote? Black bear? A determined bull moose? I waited, hoping for an answer, but only the stillness of the forest replied.

![]()

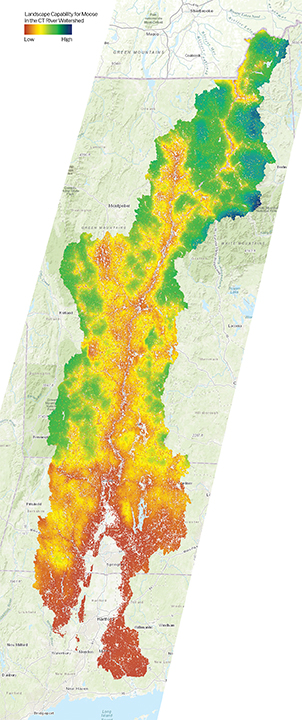

This map shows the potential capability of the land of the Connecticut River Watershed to provide habitat for moose based on 2010 data.

Moose are the largest member of the deer family (Cervidae). In North America, the family includes the omnipresent white-tail (Odocoileus virginianus), the western mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), elk (Cervus elaphus), and the tundra-dwelling caribou (Rangifer tarandus). Moose, also being circumpolar, are found throughout temperate and boreal forested regions of the northern latitudes of North America, Europe, and Asia. The species has four recognized sub-species in North America.

The Connecticut River watershed is home to Alces alces americanus, the eastern moose. Its habitat is bounded to the north where northern latitudes transition from boreal forest to a treeless landscape. The limits of their southern distribution generally coincide with the northern habitat boundary of white-tail and mule deer. This is mostly due to habitat that favors the smaller deer, but also because of the presence of the tiny parasite, meningeal nematode, the brainworm. After passing through an alternate host such as snails, eggs of the brainworm are ingested by a deer or moose. The parasites hatch in the gut before migrating to the brain and spinal column. For some reason, deer experience no ill effects from the brainworm, but for moose the parasite is always fatal. They become disoriented and lethargic, display a lack of coordination, loss of appetite, and eventually die.

Like deer, moose are ruminants, with a series of four stomachs, allowing them to digest a wide variety of plants that comprise their vegetarian diet. Food selections range from the most succulent spring growth, such as the swamp dwelling false hellebore and pond lily, to their winter diet consisting of the most fibrous woody stems like those of striped maple and balsam fir. In between those extremes, moose eat a variety moist soil plants and the fruits and nuts of deciduous trees.

Locally, moose are common among the forests of the headwaters of the Connecticut River and its northern Vermont and New Hampshire tributaries. Biologists in New Hampshire and Vermont estimate their statewide populations to be 3,500 and 2,200 moose, respectively, the majority concentrated in the northern part of each state. As you travel the river downstream, moose habitat transitions from boreal (like pines) to deciduous along the Vermont–New Hampshire border to the cultivated and developed landscapes of southern New England. Moose populations decrease correspondingly along this gradient to where they become an anomaly. Massachusetts biologists estimate the statewide moose population to be around 1,000 animals, largely in the reach of the Quabbin Reservoir, while Connecticut has around 100 moose, concentrated near the Massachusetts border.

![]()

A bull moose in the summer with velvet on his antlers in New Hampshire.

Image Credits: Map and data by North American Landscape Conservation Cooperative, Kevin McGarigal, Bill DeLuca 2015 (map). Getty Image/Serz72 (moose tracks). Daniel Berna (moose photo).

In 1781, then-Minister to France Thomas Jefferson had a complete moose skin, including hooves, sent to him in Paris. He wanted to settle a dispute with the French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, who insisted that American mammals and people (i.e. Indians) were categorically “smaller and weaker” than their European counterparts. Jefferson was incensed. In characteristic American fashion, the future President declared that North American moose were in fact so large that a European reindeer could trot comfortably “under the belly,” which was probably an exaggeration. To settle things, Jefferson wrote to New Hampshire Governor John Sullivan to have a specimen sent to Paris. Upon seeing the moose reassembled in Jefferson’s apartment, Buffon is said to have exclaimed, “I should have consulted you, Monsieur, before I published my book on natural history, and then I should have been sure of my facts.” All this is to say that Sullivan had no trouble fulfilling Jefferson’s request as moose were plentiful in those days. They served as an important food source for the region’s wolf and catamount populations and for the Iroquois, Saint Francis, Pemigewasset, and Abenaki Indian nations. Moose hides were also an important source of clothing material for these peoples.

A moose calf in the East Inlet Wildlife Area in Pittsburg, New Hampshire.

Moose populations started to decline in part as a result of beaver trapping. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the soft underfur of castor canadensis was prized for hat making, and even Plymouth Pilgrims, who came to America in 1620, developed a profitable trade with local tribes, exchanging shell beads known as wampum for pelts. The fur trade also drew the first English settlers to the Connecticut River Valley in the 1630s. However, the European hat craze led to over-trapping in North America, and by the end of the 17th century, beaver populations in New England had been reduced to a remnant existence. This loss of beaver-based wetlands on which moose depend for forage, along with the clear-cutting of the forest for wood products as well as agriculture, resulted in a steep decline in moose populations, and by the early 1900s, these emblems of wilderness had virtually disappeared from New England. However, with the abandonment of family hillside farms following the Civil War, New England’s forests began to grow back. And with that came many of the extirpated wildlife, including deer, moose, and beaver. As the 20th century progressed, slowly and surely, moose and deer populations grew. First from remnant populations in Maine and Quebec. Then, spreading to northern New Hampshire and Vermont until late the 1990s when moose could be observed, in varying numbers, throughout the Connecticut River watershed.

When I began my career as a wildlife biologist with the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department in 1980, moose were still so uncommon that the biological staff recorded every moose encountered in the course of our field work. In those days, an annual total for me might be two or three moose. However, in the presence of abundant habitat and the absence of any native predator (e.g. wolves, catamounts, or First People), moose populations in northern New England grew quickly. So much so that the very habitat that fostered such growth was becoming deteriorated by hungry moose. A human impact was being felt too. Foresters complained young trees were being wiped out by the voracious cervids. Maple syrup makers complained that moose in their daily travels were readily walking through their expensive pipeline systems and the grim statistic of highway fatalities resulting from collisions with moose were increasing.

In response to this turning of the tide, wildlife agencies in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont established regulated moose hunting seasons in 1980, 1988, and 1993 respectively. Through diligent data collection and thorough analysis, each state’s biologists carefully honed their respective hunting seasons. By the end of the first decade of the 21st century, moose populations had returned to an equilibrium with their habitat. But just as this over-population threat was resolved a new and dangerous threat emerged.

Shorter winters due to climate change may seem like a blessing. What is there to argue about lower home heating costs, less snow to shovel, and a longer growing season? Well, nothing, especially if you are a tick. The longer growing seasons are creating longer spring and fall feeding periods (questing) for the region’s tick populations. This turn of events is not only allowing tick populations to grow in size but also to expand their regional distribution too. As the now infamous and all too common black-legged, or deer tick (Ixodes damini), has wreaked havoc on the human population, the moose tick (Dermacentor albipictus) is seriously impacting New England’s moose population.

Unlike the multiple-host deer tick, dermacentor is a one-host tick. They will undergo all three of their developmental molts (nymph to larva to adult) on a single animal. Gravid (pregnant) females attach to their preferred host during their fall questing period. Once attached to the moose, they remain there for the entire winter nourishing their eggs with the host’s blood. As spring arrives, the females detach themselves and fall to the ground where they begin laying thousands of their fully developed eggs. Like all ticks, notorious for their blood sucking tenacity, the moose tick has been linked to poor over-wintering survival and poor neonatal development.

Moose infested with over-wintering ticks excessively lick themselves seeking relief from the irritation caused by what can be tens of thousands of individual feeding ticks. Persistent licking leads to loss of hair and the important insulating quality it provides. This in turn leads to excessive heat loss and an increase in the consumption of stored energy reserves (fat). Premature fat loss can lead to rapid body weight loss, hypothermia, and starvation. In the case of pregnant moose, calves are born underweight and likely receive poor post-natal nutrition as its mother attempts to recover her own body condition. Adult moose have been reported with having 100,000 winter ticks attached, and calves can host as many as 15,000 ticks at once. Research indicates a moose calf with a high tick load can lose approximately half of its total blood volume over two to four weeks. Poor physical condition also makes moose more susceptible to other debilitating parasites such as lungworms (Varestrongylus) and roundworms (Parelaphostrongylus). Fortunately, research by the states of Vermont and New Hampshire and the Province of Quebec is leading to a better understanding of this complex problem and to hopeful answers.

Despite the fact that moose sightings are down significantly from the late 2000s, there is hope. Data from independent studies reported by the wildlife agencies of Vermont and New Hampshire indicate that lower overall tick counts appear to correlate with current moose population densities. However, as climate change continues to impose shorter winters on the ecosystem, conclusive results will require much more study. Still, one can take a slow drive through the moose country of the northern reaches of the Connecticut River watershed during the low-light hours of dawn and dusk and have a reasonable chance to spot this endearing symbol of the wild northern forest.

A moose wanders through the fall woods in Easton, New Hampshire.

Image Credits: Daniel Berna (moose calf). Duane Cross (adult moose).

About the Photographers

Duane Cross is a photographer living in northern New Hampshire who began photographing local wildlife in 2008. His favorite subjects are black bears and moose. When he can’t find bears and moose, he photographs any wildlife that wanders in front of his lens, usually fox, loons, and other birds. His website is duanecrosspics.com.

Daniel Berna is a wildlife photographer based in Newbury, Vermont. Capturing close-up action shots is his specialty. Daniel worked as an appraiser of conservation lands for over thirty years, which allowed him to explore Vermont’s beautiful farmland, wetlands, and forests. Many of his earliest photos were taken “on the job.” Now retired, he spends hours at a time in his hunter’s blind and kayak waiting for the perfect shot. He isn’t afraid to get cold, wet, or dirty in the pursuit. His photographs have been featured in the Vermont Fish & Wildlife calendar for the past five years. More of his work can be found at danielberna.com or his Instagram account @danielberna5462.