Qwannitucket

Image Credit: Getty Image/Jupiterimages.

Qwannitucket, the Long Tidal River land known as the Connecticut River Valley, is the living pulse of this region currently known as New England. This article, which focuses on the lower valley of the Connecticut River, is intended to raise awareness in modern society about the beautiful resource that connects north to south, mountains to ocean, the swimmers, winged, four-legged, two-legged, and all the living beings known and unknown that dwell here. I say life known and unknown because there is so much about the river that is unknown, misunderstood, and/or ignored by modern society.

My knowledge of the River began as a child camping out and traveling the river with my family (my father modified speed boats among other things and in 1961 had the unofficial fastest outboard-powered boat in the Hartford area…a 14-foot Penn Yan reinforced and modified by him to hold a 75 horsepower Evinrude that exceeded 50 mph). While my dad grew up paddling canoes, I grew up swimming and traveling in speed boats, then later on canoes, kayaks, and finally building trimarans and other hybrid canoes.

To better understand the river and how humans have interacted with “Her” for the past 12,000-plus years, here is a quick overview of Indigenous lifestyle and society on this river before colonial times.

Indigenous people from this area are often referred to using names that evolved during colonization like “Woodlands Indians,” and while this is true of many inland groups, Natives along the lower River Valley would more accurately be described as River and Coastal dwellers.

All Native American communities throughout the valley speak variants of the Algonquin language.

Names that came into use during colonial times include the Pequots, who trace back to the Mohicans (or Maheekanew, the original name). The Mohegan of Uncasville were Pequot before they broke away and called themselves Mohegan. Natives throughout the lower Connecticut River Valley and Narragansett, Montauk, and Wampanoag were connected by way of Long Island Sound and the Atlantic. Qwannitucket was the ideal central artery with its fertile plains and abundant water. The River and its tributaries connected all these communities, which were primarily inhabited by coastal and river dwellers, not woodland dwellers.

The area described above was the immediate neighborhood in which all communities could reach each other within a day or two (and often much faster) by use of tides and widespread maritime skill.

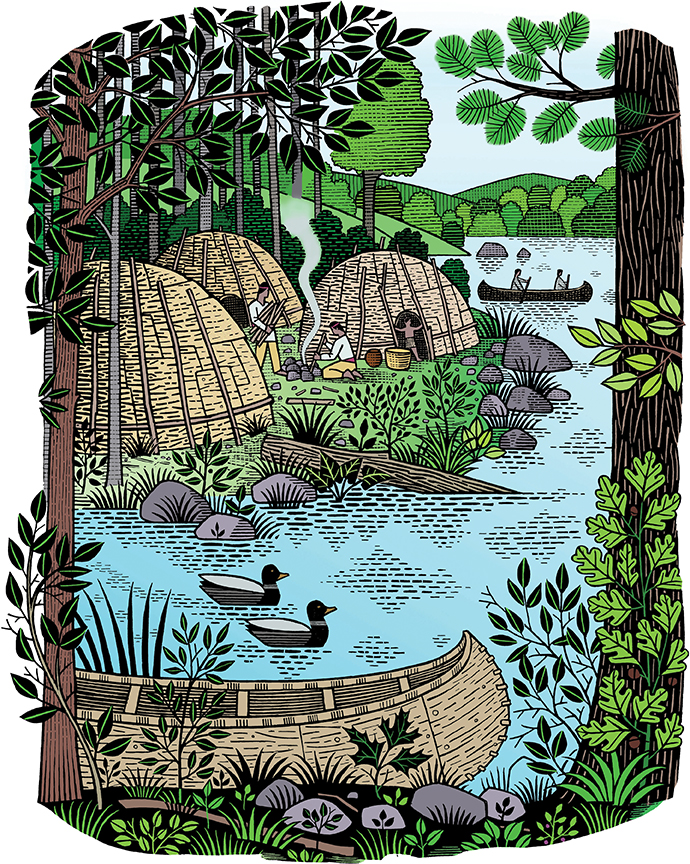

A nuswetu re-creation at Fruitlands Museum in Massachusetts.

Image Credit: Victor Grigas/Wikimedia Commons/CC-BY-SA-3.0.

In pre-colonial days, the typical family had two homes, one for summer and another for winter. The wigwam or wetu (forerunner of Buckminster Fuller’s Geodesic Dome) was the summer home, usually constructed of cedar saplings and covered with woven cattail mats, the circular structure being 12–14 feet in diameter with one fire pit in the middle. The cattails provided a natural “air conditioning,” letting fresh air circulate through. They were also waterproof and kept the rain out.

The summer home was intended for the immediate family near the river in the meadows or flood plain. It was here the people planted and grew beans, squash, pumpkin, and of course, corn, which made its way up from Central America around 1,000–1,200 years ago.

Native people here cultivated crops, gathered wild plants, and fished for their primary diet. The popular myth that hunting was the primary food source developed during and after colonization when most Natives were removed, or fled, from their traditional locations to less fertile lands and reservations where people were forced to hunt far more than they did before colonization. Hunting was in fact mainly done during the winter to supplement the food that had been dried and stored earlier in the year for the winter home.

The winter home was larger and was made for the extended family, again with a sapling frame in an oval shape (the so-called Quonset Hut, another invention based on Indigenous technology) called Nuswetu, a Wampanoag word meaning “house of three fires,” which were placed in a row running down the middle. (The Wampanoag language is one dialect of Algonquin, which everyone spoke in this whole region.)

The Nuswetu was located on a higher more protected area, usually not too far from the wetu. The Nuswetu was covered with large sections of tree bark (usually elm) which provided good insulation and protection against the elements. It was here that the people would spend the winter making and repairing tools, nets, whatever they needed. During the winter there was music, games were played, and stories would be told, retold, and new ones added, the fires being the screen that illuminated the narrative.

The large corn fields in the meadows of Rocky Hill, Connecticut, where the fields give way to the wooded hills a short distance from the River, is a typical setting from the past. There, archaeologists have uncovered various sites from hundreds to thousands of years old. These sites are often referred to as Native American when, at the time, there were no “Americans” native or otherwise. Besides arrowheads and tools, large shell heaps have been uncovered. The shells are from present-day Long Island, New York, further confirmation that Indigenous people had long and deep connections to the regional waterways with the means to travel them in a timely fashion.

The primary vehicle for transportation in those times was the canoe, or misoon. The misoon, commonly known as a “dugout,” was a large tree trunk that was not dug out at all. It was burned out over days by controlled and carefully tended small fires along the length of the trunk. Misoon ranged in size from 10 feet to 50 feet or longer, depending on its function. Every family had access to one just as cars are used today, with water being the road. There was even a form of public transportation because in places where sections of the river or stream were low and rocky, misoon were placed there so people could travel into less accessible areas with relative ease. This enabled trading, visiting relatives, and giving— generosity is an attribute Native people admire and strive to attain. Misoon also facilitated traveling with the tides and seasons throughout the long tidal river network that connected the lower valley populated by numerous Algonquin-speaking communities. These communities maintained connections throughout the valley and into Nipmuc and Abenaki territory (both of whom are actually Woodland people) in the northern interior.

As you can see, Qwannitucket is an ancient stronghold of the Algonquin civilization that stretches far beyond the valley, and has been a point of departure for countless journeys across time and throughout this hemisphere (which, by the way, was known as Turtle Island, but that’s a story for another day).